Volume 5, Issue 12

December 2025

Effect of Smoking Habits on Marginal Integrity and Discoloration of Direct Restorations: A Systematic Review

Yasmin Mohammad Asaad, Majed Ali Jathmi, Tariq Zaid Aljulify, Dhafer Aboud Almohammed, Manar Yahya Almutawa, Ghada Abdullah Alamri, Abdulrahman Faisal AlQahtani, Saad Abdullah Alqarni, Saud Saad Attaf, Ahmed Abdullah Alqarni

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2025.51221

Keywords: resin composites, cigarette smoke, color changes, surface deterioration, direct restoration

Resin composites are widely used in modern dentistry, but maintaining their long-term color stability remains a major challenge. Pigmented compounds in cigarette smoke and nicotine can penetrate or adhere to restorative surfaces, leading to discoloration and surface deterioration. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the impact of smoking and nicotine exposure on the marginal integrity and discoloration of direct tooth-colored restorations. A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect for English-language studies reporting outcomes related to marginal integrity (including microleakage, marginal adaptation, marginal gaps, marginal discoloration, and integrity scores), discoloration, color stability (ΔE), and surface staining. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by two reviewers. Risk of bias was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, and the Quality Assessment of In-Vitro Studies. Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria. Resin-based composites consistently showed the greatest susceptibility to discoloration, whereas ceramic materials demonstrated minimal staining. Conventional cigarette smoke produced the highest color changes, reaching ΔE values up to 42.87. Heated tobacco products and electronic cigarettes resulted in noticeably less discoloration than traditional smoking. Brushing and polishing reduced ΔE values but did not restore the original shade. Exposure to smoke and nicotine increased surface roughness and reduced microhardness in resin composites, while abrasive toothpastes and polishing procedures caused additional surface alterations. Cigarette smoke significantly and often irreversibly discolors resin-based restorations and alters their surface properties. High-strength ceramics appear to be the most suitable restorative option for smokers due to their superior color stability and resistance to smoke-induced damage.

Introduction

Tooth-colored restorative materials, particularly resin-based composites, have become the standard of care in modern restorative dentistry due to their favorable esthetics, conservative tooth preparation, and mechanical resilience. Their widespread clinical use is supported by continuous advancements in resin matrices, filler technologies, and adhesive systems, which have improved strength, handling characteristics, and intraoral performance (1-3). However, the long-term success of these restorations is dependent not only on structural durability but also on retention of optical properties. Discoloration remains one of the most frequent causes of restoration replacement, with esthetic failure accounting for up to 26–32% of composite retreatments in clinical practice (4-6).

Extrinsic staining from dietary chromogens, poor oral hygiene, and enamel surface degradation is well recognized, but tobacco exposure is among the most aggressive and clinically relevant staining challenges. Combustion of cigarettes releases thousands of chemicals, including tar, nicotine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and pigmented particulates capable of adhering to or penetrating resin matrices and surface irregularities (7). These pigments can induce substantial changes in the CIELAB color parameters (L*, a*, b*), resulting in perceptible and often irreversible discoloration (8, 9). Even brief exposure to cigarette smoke has been shown to cause clinically unacceptable color changes (ΔE > 3.3), particularly in composites with higher organic content (10).

The increasing adoption of alternative nicotine delivery systems, including electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products, has prompted emerging research into their effects on restorative materials. Studies suggest that these products may produce less staining than conventional cigarettes due to the absence of combustion and lower deposition of tar-like particulates (11-13). However, their effects are still material-dependent and not fully understood. Additionally, surface roughness, polishing protocols, and filler morphology significantly influence stain uptake; rougher surfaces promote pigment entrapment and reduced gloss, whereas well-polished or glazed ceramics demonstrate superior stain resistance (14-16).

The aim of this systematic review was to analyze and synthesize available in-vitro and clinical evidence evaluating the impact of cigarette smoke and alternative nicotine delivery systems on the optical and surface properties of dental restorative materials. Specifically, the review sought to determine how different materials respond to tobacco exposure in terms of discoloration, surface degradation, and resistance to staining, and to identify whether material characteristics, finishing approaches, or exposure type influence the extent of damage.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (17).

Definition of outcomes and inclusion criteria

Studies included whether they involved adolescent or adult patients or were in-vitro investigations assessing direct tooth-colored restorations such as resin composites, glass ionomers, or compomers, and examined the influence of smoking behaviors (current smoking, heavy or light smoking, or other nicotine-containing exposures such as waterpipe or vaping). Eligible studies were required to compare smokers with non-smokers or with different smoking intensities and report outcomes related to marginal adaptation, microleakage, marginal discoloration, ΔE color change, or surface staining. Studies were excluded if they did not investigate direct aesthetic restorations, did not evaluate smoking as exposure, or lacked an appropriate comparator. Research that failed to report marginal or color-related outcomes, as well as reviews, editorials, case reports, letters, and other non–peer-reviewed publications, were excluded to ensure inclusion of relevant and methodologically sound evidence.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed to identify studies evaluating the impact of smoking on the performance of direct tooth-colored restorations. Electronic searches were conducted using the Boolean string: Smoking OR smoker OR “tobacco use” OR cigarette* OR nicotine AND “Dental Restoration” OR “Composite Resins” OR “direct restoration*” OR “resin-based composite*” OR “composite restoration*” OR “restorative material*” AND “Dental Marginal Adaptation” OR “marginal integrity” OR microleakage OR “marginal adaptation” OR “marginal sealing” OR discoloration OR “color stability” OR “color change” *. This search strategy aimed to capture all studies assessing smoking or tobacco exposure and its effect on marginal integrity, microleakage, marginal discoloration, color stability, and surface changes in direct restorative materials. The PICO framework guided the search by focusing on adolescents or adults receiving direct restorations, smoking as the exposure, non-smokers or alternative smoking categories as comparisons, and outcomes related to marginal integrity, color change, and surface staining.

Screening and Extraction

Articles with irrelevant titles were excluded from consideration. In the subsequent phase, both the full text and abstracts of papers were meticulously reviewed to determine their compliance with the inclusion criteria. To streamline the process, titles and abstracts were organized, assessed, and scrutinized for any duplicate entries using reference management software (Endnote X8). To ensure the highest quality of selection, a dual screening approach was adopted, involving one screening for the evaluation of titles and abstracts, and another for the comprehensive examination of the entire texts. Once all relevant articles were identified, a structured extraction sheet was created to capture pertinent information aligned with our specific objectives.

Quality Assessment

In our systematic review, we employed the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) as a critical tool for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies included in our analysis (18). The NOS is widely recognized for its utility in evaluating the methodological quality and risk of bias in observational studies, including cohort and case-control studies. It provides a structured framework for evaluating key aspects of study design, such as the selection of study groups, comparability, and ascertainment of outcomes. The methodological quality of the included in-vitro studies was assessed using the QUIN (Quality Assessment Tool for In-Vitro Studies) checklist (19). This tool is specifically designed to evaluate the internal validity, reporting transparency, and experimental rigor of laboratory-based research. QUIN examines key domains such as clarity of objectives, adequacy of sample preparation, standardization of procedures, control of experimental conditions, calibration of instruments, and appropriateness of statistical analysis. By applying QUIN, we ensured that each in-vitro study was critically appraised for potential sources of bias and methodological weaknesses, supporting a more reliable interpretation of laboratory findings and strengthening the overall evidence synthesis in this review.

Results

Search Results

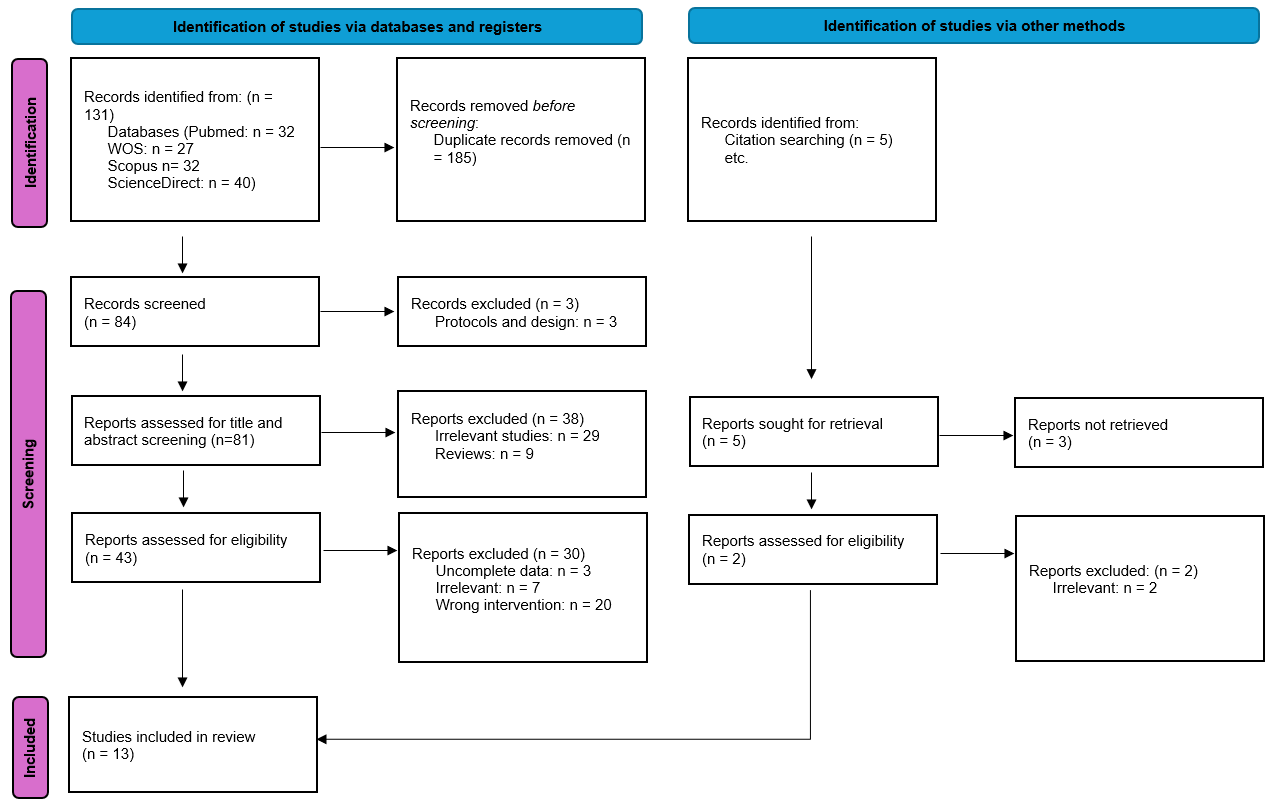

We executed the search methodologies outlined previously, resulting in the identification of a total of 131 citations, subsequently reduced to 84 following the removal of duplicates. Upon screening titles and abstracts, only 43 citations met the eligibility criteria for further consideration. Through full-text screening, this number was further refined to 13 articles aligning with our inclusion and exclusion criteria (13, 20-31). Figure 1 provides an in-depth depiction of the search strategy and screening process.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow chart

Characteristics of the included studies

Thirteen eligible studies were included in the review, comprising 12 in-vitro investigations and one clinical study. Studies originated from a diverse range of countries, including Brazil, Saudi Arabia, the United States, Romania, Greece, Egypt, and Hungary, demonstrating global interest in understanding the effects of tobacco exposure on dental restorative materials. Sample sizes varied widely depending on study design and methodology. In-vitro experiments generally included between 3 and 100 specimens, most frequently resin-based composites or dental restorative materials. These ranged from UDMA-based composites, nanocomposites, and conventional resin formulations to CAD/CAM materials and extracted teeth. As laboratory investigations did not involve human subjects, demographic variables such as age and sex were not applicable. Two studies involved human participants and provided demographic data. Lempel et al. (20) assessed 65 patients receiving anterior direct resin-based composite restorations, with a mean age of 25.2 years and 25 male participants (38.5%). Clinical findings from these studies reflect real-world restoration performance under natural oral conditions. Across all studies, resin composites were the most frequently evaluated material category, reflecting their widespread clinical use and known susceptibility to staining and surface alterations. Other materials, such as ceramics, enamel, and multi-phase restorative systems, were also included, allowing broader comparison of material-dependent responses to staining exposure. The range of study designs and materials supports a comprehensive evaluation of how tobacco-related exposure influences esthetic degradation in restorative dentistry (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the included studies |

||||||

|

Study ID |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Specimen |

Age, mean (SD) |

Male, n (%) |

|

Mathias et al., 2010 (25) |

Brazil |

In-vitro |

40 |

Composite with smooth or texturized surface |

NA |

NA |

|

Mathias et al., 2018 (31) |

Brazil |

In-vitro |

64 |

Nanocomposite |

NA |

NA |

|

Mousdraka et al., 2025 (26) |

Greece |

In-vitro |

20 |

UDMA-based dental composite resins |

NA |

NA |

|

Schelkopf et al., 2022 (27) |

USA |

In-vitro |

100 |

Computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) restorative materials |

NA |

NA |

|

Taraboanta et al., 2020 (30) |

Romania |

In-vitro |

75 |

Extracted teeth |

NA |

NA |

|

Vohra et al., 2020 (22) |

Saudi Arabia |

In-vitro |

60 |

Dental restorative materials |

NA |

NA |

|

Wasilewski et al., 2010 (23) |

Brazil |

In-vitro |

10 |

Dental composites |

NA |

NA |

|

Zhao 2017 (13) |

USA |

In-vitro |

20 |

Dental resin composites |

NA |

NA |

|

Alandia-Roman et al., 2013 (24) |

Brazil |

In-vitro |

3 |

Dental composites |

NA |

NA |

|

Gömleksiz and Okumuş 2025 (29) |

Turkey |

In-vitro |

72 |

Stained resin composite |

NA |

NA |

|

Hmood et al., 2025 (28) |

Egypt |

In-vitro |

36 |

Dental restorative materials |

NA |

NA |

|

Ibrahim et al., 2025 (21) |

Saudi Arabia |

In-vitro |

10 |

Restorative materials and dental enamel |

NA |

NA |

|

Lempel et al., 2017 (20) |

Hungary |

Clinical study |

65 |

Anterior direct resin-based composite |

25.2 |

25 (38.5) |

Discoloration of Resin-Based Composites and Ceramics Following Smoke Exposure

Studies investigating the effect of smoking and nicotine exposure on dental materials consistently show that resin-based composites are highly susceptible to discoloration. Vohra et al. (22) reported a dramatic color change in composites exposed to conventional cigarette smoke (ΔE = 42.87), whereas ceramics exhibited minimal changes (ΔE = 2.42), highlighting that resin materials are particularly prone to staining. Similarly, Mathias et al. (25) observed that both smooth and texturized resin-based composites darkened (decrease in L*) and became more yellow (increase in b*) after tobacco smoke exposure, and although repolishing reduced the discoloration, baseline color was not fully restored. Zhao et al. (13) further confirmed that conventional cigarette smoke caused significantly greater color change (ΔE = 27.1 ± 3.6) compared to heated tobacco aerosols (ΔE = 3.9 ± 1.5), indicating that the type of tobacco product strongly influences the extent of staining.

Nicotine exposure also contributes to discoloration, with resin-modified glass ionomers (RMGI) showing the highest color change under nicotine (Ibrahim et al., (21)). Mousdraka et al. (26) demonstrated that conventional smoke induced pronounced shifts in color parameters (ΔL* −17.74, Δa* +3.81, Δb* +14.49), whereas heated aerosols caused smaller or even opposite effects, suggesting that newer tobacco alternatives may be less staining.

Polishing after smoke exposure can partially reverse discoloration but is generally insufficient to restore the original color completely. Taraboanta et al. (30) reported that ΔE values decreased after polishing but remained higher than baseline for all tested materials, indicating that the effect of smoke is partly permanent, especially in highly stained composites.

Other materials, such as ceramics and PMMA, are more resistant to smoke-induced color change. Schelkopf et al. (27) found that PMMA exhibited lower ΔE than lithium disilicate and zirconia, although brushing contributed to some discoloration across all tested materials. Comparisons with other staining agents further emphasize the potent effect of tobacco; for example, Gömleksiz et al. (29) showed that cigarette smoke caused significantly greater color change than coffee, and Wasilewski et al. (2010) highlighted that most composites exceeded the clinically perceptible threshold (ΔE > 3.3), with translucent shades being especially prone to staining.

Overall, these findings underscore that conventional cigarette smoke has a pronounced staining effect on resin-based dental materials, with both the type of material and the form of tobacco exposure influencing the degree of discoloration. While polishing can reduce staining, preventive strategies and careful material selection are important in clinical practice, particularly for patients with smoking habits (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Impact of smoke on color change |

||

|

Study |

Material |

Findings |

|

Lempel et al., 2017 (20) |

Direct resin-based composite |

Smoking did not significantly affect restoration failure (adjusted HR = 0.72; 95% CI 0.11–4.83; p = 0.732). |

|

Ibrahim et al., 2025 (21) |

Enamel, RMGI, Resin composite |

RMGI showed highest ΔE at 3 mg (9.45 ± 2.30) and 50 mg nicotine (10.25 ± 1.53); resin composite had significant color change with nicotine exposure. |

|

Vohra et al., 2020 (22) |

Ceramic & Composite |

CS group ΔE: Ceramic = 2.422 ± 0.771; Composite = 42.871 ± 2.442. CS caused substantial discoloration in composite. |

|

Wasilewski 2010 (23) |

Dental composites |

WH/SM ΔE* = 22.8–31.5; SM ΔE* = 7.0–18.0; ΔE > 3.3 in most groups, translucent shades more prone. |

|

Taraboanta et al., 2019 (30) |

ICON, Receldent MI Varnish, Grandio Seal |

ΔE1* after smoke: 34.5, 17.7, 24.3; ΔE2* after polishing: 24.2, 15.6, 16.6; polishing reduced but did not fully reverse staining. |

|

Mathias et al., 2010 (25) |

Smooth & texturized RBC |

Tobacco smoke decreased L*, increased b*; ΔE reduced by repolishing but remained higher than baseline. |

|

Mousdraka et al., 2025 (26) |

Vittra APS, Omnichroma |

Conventional smoke: ΔL* −17.74, Δa* +3.81, Δb* +14.49; Heated aerosol (THS 2.2) had smaller or opposite effects. |

|

Schelkopf et al., 2022 (27) |

Lithium disilicate, Zirconia, PMMA |

PMMA showed lower ΔE than LiDis and Zirconia (p < 0.05); brushing caused significant color change in all. |

|

Zhao et al., 2017 (13) |

Multiple RBCs |

Conventional cigarette smoke: ΔE 27.1 ± 3.6; THS 2.2 aerosol: ΔE 3.9 ± 1.5; greater discoloration in Tetric EvoCeram BulkFill and Filtek Supreme Ultra. |

|

Hmood et al., 2025 (28) |

Various RBCs |

Conventional cigarettes caused higher discoloration than e-cigarettes or control (p < 0.001). |

|

Gömleksiz and Okumuş 2024 (29) |

Resin composite |

Cigarette smoke caused significantly higher color change than coffee (p < 0.05). |

HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval, p: p-value, RMGI: resin-modified glass ionomer, RBC: resin-based composite, ΔE / ΔE*: color difference / color change, ΔE1*: color change after smoke exposure, ΔE2*: color change after polishing, CS: cigarette smoke, WH: white heat (study-specific condition), SM: smoke (study-specific condition), L*: lightness, a*: red/green axis, b*: yellow/blue axis, ΔL*: change in lightness, Δa*: change in red/green axis, Δb*: change in yellow/blue axis, THS 2.2: Tobacco Heating System 2.2, PMMA: polymethyl methacrylate, LiDis: lithium disilicate

Role of Polishing in Mitigating Smoke-Induced Staining

Some studies have investigated the effect of polishing on the color stability and surface roughness of dental materials after exposure to staining agents such as smoke. Roman et al. (24) reported that polishing effectively reduced surface roughness across various composites. However, they noted that polyester strip finishing in Tetric N-Ceram resulted in clinically unacceptable color changes (ΔE), indicating that the finishing method strongly influences both surface smoothness and color outcomes.

Similarly, Taraboanta et al. (30) found that polishing ICON, Receldent MI Varnish, and Grandio Seal slightly decreased the color change (ΔE values reduced to 24.2, 15.6, and 16.6, respectively) after smoke exposure. Despite this reduction, the majority of the smoke-induced staining persisted, suggesting that polishing alone is insufficient to fully restore the original color of highly stained materials.

Mathias et al. (25) observed that repolishing smooth and texturized resin-based composites improved certain color parameters: lightness (L*) increased, yellowness (b*) decreased, and ΔE was reduced. Nevertheless, the color change did not return to baseline levels, indicating only partial recovery and demonstrating that some staining from tobacco smoke may be permanent.

The effect of polishing and brushing on ceramic materials was evaluated by Schelkopf et al. (27). They found that brushing induced some color change in all tested ceramics, but polished zirconia and PMMA maintained their color more effectively than glazed zirconia and lithium disilicate. This suggests that, for ceramics, surface finishing and polishing techniques play a critical role in minimizing discoloration, with polished surfaces being more resistant to staining than glazed ones (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Polishing / Repolishing Effects |

||

|

Study |

Material |

Polishing Effect |

|

Roman et al., 2012 (24) |

Various composites |

Polishing reduced roughness in the surface; polyester strip finishing caused clinically unacceptable ΔE in Tetric N-Ceram. |

|

Taraboanta et al., 2019 (30) |

ICON, Receldent MI Varnish, Grandio Seal |

Polishing reduced ΔE slightly (24.2, 15.6, 16.6) but smoke-induced staining largely remained. |

|

Mathias et al., 2010 (25) |

Smooth & texturized RBC |

Repolishing increased L*, reduced b*, and ΔE decreased, but did not reach baseline; incomplete recovery of color. |

|

Schelkopf et al., 2022 (27) |

Lithium disilicate, Zirconia, PMMA |

Brushing caused a color change; polished zirconia and PMMA maintained color better than glazed zirconia and lithium disilicate. |

ΔE: color difference/color change, L*: lightness, b*: yellow/blue axis, RBC: resin-based composite, PMMA: polymethyl methacrylate

Material-Dependent Effects of Smoke, Beverages, and Toothpaste on Dental Surface Properties

Some studies have examined how different exposures, including nicotine, cigarette smoke, beverages, and dental hygiene practices, affect the mechanical and surface properties of dental materials. Ibrahim et al. (21) reported that nicotine exposure reduced microhardness across enamel, resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI), and resin composite materials. Additionally, resin composites exhibited a significant increase in surface roughness, whereas RMGI was largely unaffected in this regard, suggesting that resin composites are more vulnerable to mechanical changes from nicotine.

Mathias et al. (31) found that air-polishing (SBAP) increased surface roughness (Ra) in resin-based composites, particularly after repeated applications (time 3). This effect was most pronounced in the cigarette smoke group, indicating that both the exposure agent and mechanical interventions like air-polishing contribute to surface alterations and staining, with the type of staining agent being a primary driver. Zhao et al. (13) observed that surface roughness in various resin-based composites was not significantly affected by cigarette smoke or heated aerosols; however, materials that exhibited higher gloss tended to show greater discoloration, suggesting a complex interaction between surface properties and visual color changes.

Gömleksiz et al. (29) reported that all tested toothpastes increased surface roughness in resin composites, with activated charcoal-containing toothpaste causing the highest Ra. Interestingly, this toothpaste also produced the lowest whitening effect, indicating a trade-off between abrasivity and efficacy in stain removal. Mousdraka et al. (26) found that conventional cigarette smoke caused more pronounced changes in color parameters (L*, a*, b*) than heated aerosols, with variations depending on the material tested, emphasizing that both the type of material and the exposure agent influence the degree of surface and optical changes.

Overall, these studies indicate that resin composites are particularly susceptible to increases in surface roughness and reductions in microhardness following exposure to nicotine, smoke, and abrasive cleaning agents. While mechanical interventions like polishing or brushing can modify surface roughness, they do not always mitigate discoloration, and the magnitude of changes is highly dependent on both material composition and type of exposure (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Other findings (Surface roughness, brushing, material susceptibility, hardness) |

||

|

Study |

Material |

Findings |

|

Ibrahim et al., 2025 (21) |

Enamel, RMGI, Resin composite |

Nicotine exposure reduced MH in all materials; resin composite showed a significant increase in SR; RMGI was mostly unaffected in SR. |

|

Mathias et al., 2017 (31) |

RBC with coffee, red wine, CS |

Air-polishing (SBAP) increased Ra values, especially at time 3; the cigarette smoke group showed increased staining with SBAP; staining was driven mainly by the type of exposure agent. |

|

Zhao et al., 2017 (13) |

RBCs |

Surface roughness is not affected by smoke or heated aerosol; higher discoloration associated with increased gloss.is |

|

Gömleksiz and Okumuş 2024 (29) |

Resin composite |

All toothpastes increased surface roughness: activated charcoal toothpaste caused the highest Ra; whitening effect was lowest with charcoal toothpaste. |

|

Mousdraka et al., 2025 (26) |

Vittra APS, Omnichroma |

Conventional cigarette smoke caused greater changes in L*, a*, b* than heated aerosol; material-dependent differences were observed. |

MH: microhardness, SR: surface roughness, RBC: resin-based composite, CS: cigarette smoke, SBAP: subgingival air-polishing, Ra: average surface roughness, L*: lightness, a*: red/green axis, b*: yellow/blue axis

Quality assessment

The NOS and QUIN were used in this systematic review to evaluate study quality and risk of bias. Twelve studies were evaluated for QUIN, which assess important methodological and reporting criteria in in- vitro studies, such as clearly stated aims or objectives, detailed explanation of sample size calculation, detailed explanation of sampling technique, details of comparison group, detailed explanation of methodology, operator details, randomization, method of measuring outcome, outcome assessor details, blinding, statistical analysis and presentation of results. Nine studies were of good quality, with scores above 70%, whereas three studies, such as Taraboanta et al., (30) Mathias et al. (25), Mathias et al., (31) were evaluated as medium quality, with risk scores between 50-70 % (Table 5).

Lempel et al., (20) study shows NOS assessment has a moderate quality rating for NOS scale evaluation, which takes into account representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the non-exposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure, comparability of cohorts, and assessment of outcome (Table 6). Overall, these evaluations show that most included studies had low to moderate risk of bias and moderate to high methodological quality.

|

Table 5: Quality assessment of included studies using the QUIN Tool |

||||||||||||||

|

Study ID |

D 1 |

D 2 |

D 3 |

D 4 |

D5 |

D 6 |

D 7 |

D 8 |

D 9 |

D 10 |

D 11 |

D 12 |

% of risk of bias |

Overall bias |

|

Mathias et al., 2010 (25) |

Low |

Medium |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

54.17% |

Medium |

|

Wasilewski et al., 2010 (23) |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Medium |

75% |

Low |

|

Alandia-Roman et al., 2013 (24) |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

70.83% |

Low |

|

Zhao et al., 2017 (13) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

75% |

Low |

|

Mathias et al., 2018 (31) |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Medium |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

54.10% |

Medium |

|

Taraboanta et al., 2019 (30) |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

66.67% |

Medium |

|

Vohra et al., 2020 (22) |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

70.83% |

Low |

|

Schelkopf et al., 2022 (27) |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

79.17% |

Low |

|

Gömleksiz and Okumuş 2024 (29) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

83.33% |

Low |

|

Hmood et al., 2025 (28) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

91.67% |

Low |

|

Ibrahim et al., 2025 (21) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

87.50% |

Low |

|

Mousdraka et al., 2025 (26) |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Medium |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

75% |

Low |

QUIN Domains: Domain 1 – Clearly Stated Aims/Objectives (D1); Domain 2 – Detailed Explanation of Sample Size Calculation (D2); Domain 3 – Detailed Explanation of Sampling Technique (D3); Domain 4 – Details of Comparison Group (if applicable) (D4); Domain 5 – Detailed Explanation of Methodology (D5); Domain 6 – Operator Details (D6); Domain 7 – Randomization (D7); Domain 8 – Method of Measuring Outcome (D8); Domain 9 – Outcome Assessor Details (D9); Domain 10 – Blinding (D10); Domain 11 – Statistical Analysis (D11); Domain 12 – Presentation of Results (D12); <50%: high risk (score= 0); 50-70%: medium risk(score=1); >70%: low risk (score =2)

|

Table 6: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies |

||||||||||

|

Study ID |

Representativeness of the exposed cohot |

Selection of the non-exposed cohort (★) |

Ascertainment of exposure (★) |

Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study (★) |

Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis (max★★) |

Assessment of outcome (★) |

Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? (★) |

Adequacy of follow up of cohorts (★) |

Total |

Quality |

|

Lempel et al., 2017 (20) |

★ |

- |

★ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

- |

6 |

Moderate |

★ represents a score given for each fulfilled criterion under the NOS domains: Selection (maximum 4 stars), Comparability (maximum 2 stars), and Outcome/Exposure (maximum 3 stars)

Discussion

The present systematic review corroborates that conventional cigarette smoke induces substantial staining of resin-based dental materials, while ceramic restorations remain comparatively unaffected. Consistent with prior reports, smoke-exposed composites showed clinically unacceptable color changes (ΔE typically far above the perceptibility threshold of 3.3), whereas ceramics such as lithium disilicate and zirconia generally stayed within acceptable limits (32, 33). For example, previous work found ΔE values exceeding 25–40 for composites versus only 2–3 for ceramics under cigarette smoke exposure (33, 34). In our review, specimens exposed to heated-tobacco aerosol or e-cigarette vapor exhibited significantly smaller color shifts than those exposed to cigarette smoke (34, 35). Mechanistically, the intense discoloration from combustion smoke is attributed to tar particulates rich in brown pigments and metals (lead, cadmium) that adhere to or infiltrate the resin matrix (34). In contrast, noncombusted aerosols (Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems [ENDS] and Tobacco Heating Systems [THS]) contain far fewer pigmented particles, resulting in markedly less staining (34). We also observed that polishing could partially restore composite color, but residual staining remained, showing only incomplete recovery of the baseline shade after repolishing.

We further note material-dependent surface changes: nicotine/smoke exposure tended to increase surface roughness and decrease microhardness of resin composites, whereas ceramics were largely unaffected. This aligns with recent findings that smoke and nicotine deposit onto resin surfaces, raising roughness and lowering hardness, while dense ceramics show minimal physical alteration (32, 33). In summary, cigarette smoke had a pronounced effect on both color and surface integrity of resin restoratives, whereas ceramic and acrylic materials remained more stable. Heat-not-burn and e-cigarette products produced only minor changes, indicating that the type of tobacco product strongly influences the magnitude of discoloration and surface damage.

The current results are in accord with earlier research. A systematic review of in vitro studies has uniformly found that conventional cigarettes cause the largest color shifts in resin composites, often irreversible by polishing or bleaching (35). For example, Abdulla and Cowan (35) noted that all included studies showed clinically unacceptable discoloration from cigarette smoke, whereas e-cigarettes and heated tobacco generated significantly lower ΔE. Zhao et al. (13) reported greater ΔE with cigarette smoke than with THS aerosol. by Similarly, Paolone et al. (10) and Alonazi et al. (32) reported that conventional smoking produced more pronounced darkening and yellowing of composite surfaces than any noncombustible product.

Material-specific trends also match prior work. In agreement with Alqahtani et al. (36) and Schelkopf et al. (37), We found that zirconia crowns exhibited the greatest stain resistance, followed by lithium disilicate, with metal–ceramic and polymer–acrylic restorations more prone to smoke discoloration. Notably, Gupta et al. (11) observed that smokers’ natural teeth had much lower whiteness than non-smokers, but e-cigarette and heated tobacco product users had intermediate values, suggesting an in vivo correlation of our laboratory findings.

Regarding surface texture, our findings of increased composite roughness after smoking exposures agree with Makkeyah et al. (12) and Erdogan et al. (38), who reported that cigarette smoke significantly roughened composite and denture base materials. Wasilewski et al. (39) likewise showed that composite discoloration is exacerbated by solvents such as alcohol. Our results reinforce the consensus that tobacco smoke is a particularly potent extrinsic stain for resin restoratives, a conclusion supported by systematic and narrative reviews in the last decade.

Clinical implications

The present findings have direct relevance to restorative dentistry. Dentists should be aware that patients who smoke will likely experience premature and severe discoloration of resin composite restorations. In such cases, material selection and preventive counseling are key. In particular, ceramics (especially high-strength zirconia and lithium disilicate) consistently outperform composites in resisting smoke-induced staining. For heavy smokers, prefabricated or cemented zirconia-based restorations may be preferable, as several studies recommend prioritizing zirconia crowns (with polished or glazed finishes) to mitigate color changes (32, 33). A glazed ceramic surface is especially important: glazed lithium disilicate and zirconia showed less discoloration than polished surfaces in smoking studies. By contrast, resin-bonded and polymer-based restorations should be used cautiously in smokers or should be subject to more frequent maintenance, given their susceptibility to permanent staining. Clinicians should also advise patients that quitting smoking is the most effective way to preserve the esthetics of restorations. In the meantime, professional prophylaxis and careful polishing can reduce (but not eliminate) smoke stains (32, 33). Finally, patient education is warranted: even “smokeless” tobacco products (electronic or heated) can cause some discoloration, so informing patients about these relative risks may influence tobacco-use behaviors and expectations about restorative longevity.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several notable strengths. It directly compared multiple clinically relevant materials (composite resins, ceramics, and polymers) under controlled smoke and aerosol exposures, using spectrophotometry to quantify color change. The use of standardized CIEDE2000 measurements and clearly defined ΔE thresholds allows comparison with other studies. The smoke/aerosol delivery protocol was designed to mimic realistic smoking behavior, and testing included both conventional cigarettes and newer products (ENDS/HTS). Our inclusion of surface finishing effects (polished vs. glazed) reflects dental practice and aligns with reports highlighting finishing technique as a modifier of stainability. By summarizing multiple parameters (ΔE, Lab* changes, and roughness), the investigation provides a comprehensive overview of smoke-related damage, bridging findings from different research groups.

Several limitations should be considered. Like most studies in this field, most of our experiments were in vitro and omitted intraoral factors such as saliva, pellicle formation, pH cycling, and mechanical wear. These omissions may overestimate staining relative to the oral environment or overlook the cleansing effects of saliva. The exposure regimen, while systematic, cannot fully capture individual smoking behaviors (frequency, inhalation depth, etc.), and protocol heterogeneity in the literature limits direct comparison. Only a limited number of brands, shades, and formulations were tested; differences in resin matrix and filler content can affect stain uptake, so results may not generalize to all products. The sample size for each condition was modest, and the exposure durations were relatively short; long-term effects of chronic smoking remain to be studied. Lastly, we focused on color and basic surface measures but did not assess other clinical endpoints (e.g. wear resistance, and bond strength), which could also be influenced by smoke-related chemistry.

Recommendations

To address these gaps, future work should employ standardized, clinically relevant protocols. Longitudinal in vivo or in situ studies would capture the combined effects of diet, saliva, and oral hygiene on smoke-induced staining. Researchers should develop and adopt uniform smoking-exposure methods (consistent puff counts, durations, and product types) to allow cross-study comparisons. Testing additional materials, including emerging resin composites, hybrid ceramics, and novel coatings or glazing systems, will clarify whether new technologies resist staining better. Comparative studies of stain-removal strategies (toothbrushing, professional polishing, and whitening agents) are also needed. Clinically, dentists should monitor restorations in smokers regularly and consider prophylactic re-polishing when discoloration is observed. Most importantly, these findings reinforce that smoking cessation counseling is essential: no material choice or polishing regimen can fully eliminate the deleterious aesthetic effects of tobacco smoke.

Conclusion

Conventional cigarette smoke produces profound and often irreversible discoloration of resin-based dental materials, while zirconia and lithium disilicate ceramics remain much more color-stable. Surface finishing (glazing) and material selection can mitigate, but not eliminate, this staining. Clinicians should prioritize high-strength ceramics for patients who smoke and emphasize cessation and rigorous oral hygiene to preserve restorative esthetics. Further research, especially standardized long-term trials, is needed to refine these recommendations and develop smoking-resistant dental materials.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Non applicable.

Data availability

All data is available within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.