Volume 5, Issue 12

December 2025

Effect of Aging and Thermocycling on the Marginal Seal of Adhesive Materials

Summer Farouk Khatib, Manal Abdulrahman Bedawi, Ahmed Emad Alhassan, Dalal Abdul Wahab Jiffry, Abdulmalik Saud Alsalem, Lama Abulola Alsayegh, Abdulaziz Yahya Faya, Muna Saad Alotibi

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2025.51218

Keywords: marginal seal, aging, thermocycling, adhesive dentistry, microleakage

Adhesive dentistry is one of the most complicated branches of dentistry due to the complex structure of dentin and enamel and the different, technique-sensitive adhesive materials used. When applying adhesive restorative material, obtaining an optimum marginal seal is one of the main goals. However, several factors can affect the integrity of the marginal seal, resulting in restoration failure. These factors include thermocycling and aging. The adhesive materials are subjected to different factors that significantly affect their properties, leading to microleakage and demanding restoration replacement. Microleakage results from the thermal contraction of the adhesive material after being subjected to different temperatures, the polymerization shrinkage after curing of the adhesive material, mechanical stresses resulting from the occlusal forces applied to the tooth and the restoration, and water sorption of the restoration. Additionally, the improper adaptation of the resin composite material and adhesives at the tooth structure-restoration interface plays a crucial role in the failure of the marginal seal. In the oral cavity, the adhesive materials are constantly subjected to thermocycling due to the intermittent temperature changes. This thermocycling causes the restoration to develop a viscoelastic response that compromises the integrity of the polymeric layer, leading to debonding of the adhesive layer, loss of marginal seal integrity, and restoration failure. The adhesive materials are subjected to aging through chemical, mechanical, biological, and physical processes, which are subjected to over time, resulting in the deterioration and degradation of their components. Despite the great development in adhesive dentistry, aging and thermocycling of the adhesive material remain a great challenge to maintaining the integrity of the marginal seal.

Introduction

The primary goal of adhesive dentistry is to bond restoration to the enamel, dentin, or both. However, this goal faces several challenges due to the difference in the microstructure, histological, and chemical composition between enamel and dentin (1). Enamel composition is highly mineralized, with 95% to 98% of its composition consisting of inorganic matter. The main inorganic component of enamel is hydroxyapatite crystals, which account for 90% to 92% of the volume of the inorganic matter and are arranged in prisms and rods (2). Between these rods and prisms, a network of organic components is present (1). Whereas dentin, though considered a highly mineralized tissue, has lower levels of inorganic matter than enamel, accounting for 70% of its composition. In addition to the different composition of dentin, its morphological composition renders it challenging for a restoration to adhere to it (1, 3). Dentin is composed of dentinal tubules occupied by odontoblast processes, with a density ranging between (19–45) × 1000/mm2 and an average diameter of 0.8–2.5 μm (4). Additionally, the diameter of the dentinal tubules increases as the distance towards the pulp decreases, resulting in increased dentin permeability in deep cavities, rendering adhesion more complicated in badly destructed teeth (1, 5).

This complex structure of the tooth and the complex adhesion techniques used in placing the composite restorations can affect its longevity. The primary reasons for adhesive restoration failure include marginal discrepancy, fracture, secondary caries, and wear (6). Some studies found that the main reason that affects the longevity of posterior composite restoration is marginal leakage resulting from poor marginal adaptation of composite materials, followed by secondary caries (6). Additionally, the cavity margin integrity and the oral hygiene of the patient play a crucial role in maintaining the longevity of the restoration and preventing the development of secondary caries (6).

Composite restorations are exposed to both mechanical and chemical degradation in the oral cavity. When these restorations are exposed to water, fluctuations in temperature, pH, and mechanical stresses in the oral cavity, the polymer matrix swells, softens, and plasticizes (7, 8). This thermocycling can cause the siloxane bonds between the filler and the coupling agent in the composite restoration to degrade, in addition to the degradation of ester bonds between the filler and the polymer matrix. This degradation occurs through the hydrolysis process of the dental composite material (7). This hydrolysis process is catalyzed by the enzymes produced by bacteria present in the oral cavity, in addition to the high alkaline (pH 13.0) or very low (pH < 2.0) acidic environments (6, 9). Additionally, the aging of the restoration can result in the deterioration of its properties, leading to marginal leakage and secondary caries, resulting in restoration failure (6).

This review article aims to elucidate the effect of aging and thermocycling on the integrity of the composite restoration and marginal adaptation of adhesive restorations. The study also aims to address the gaps existing in literature and to contribute to filling these gaps by highlighting the effect of the fluctuating oral environment on the marginal seal and, hence, the survival of the composite restoration.

Methods

This narrative review is based on a comprehensive literature search conducted on October 17, 2025, using ScienceDirect, PubMed, Wiley Library, Dynamed, MDPI, Oxford Academic, BMC, and Cochrane databases. The research utilized Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and relevant keywords, such as aging and thermocycling, and their effect on the marginal seal of adhesive restorations, to identify studies that examined aging and thermocycling and their impact on the integrity of the marginal seal and the longevity of the restoration. A manual search was also conducted using Google Scholar, and the reference lists of identified papers were reviewed to locate additional relevant studies. No restrictions were applied regarding publication date, language, participant age, or type of publication, ensuring a broad exploration of the available literature.

Discussion

Classification of Adhesive Systems

Adhesive systems are classified into three systems, which are etch-and-rinse, self-etch, and universal adhesive systems (1). The etch-and-rinse adhesive system depends on etching the enamel and dentin before bonding. It can be done in three steps, in which acid etch is applied, rinsed, and then a primer is applied, followed by a conventional adhesive. It can also be done in two or one step using a self-etch adhesive (1, 10). Regardless of the type of adhesive used, this system depends on the acidic treatment of enamel and dentin before the application of the adhesive to remove or stabilize the smear layer (11). The acidic treatment of the enamel and dentin produces microroughness, resulting in an ideal seal between the dental substrate and the resin restoration (11). Although this system has several steps and is highly sensitive, it is the most multifaceted system, since it can be used in the bonding of direct and indirect restorations, in addition to self-cured and dual-cured restorations. It can be considered the gold standard of adhesive systems (1).

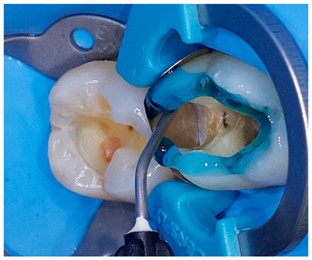

The self-etch adhesive system depends on the water component to activate the ionization potential of the acidic monomers found in the adhesive (11). The presence of the water component eliminates the rinse step (12). Self-etch adhesives demineralize the enamel and dentin and infiltrate them, reinforcing the cohesion of the resin after polymerization, resulting in an increase in the resin restoration to hydrolysis (13). However, the etching property of the self-etch adhesives is not enough to create micro-roughness in the enamel (1, 11). Therefore, practitioners use a selective etching of enamel to increase the micro-roughness and demineralization, hence growing the mechanical retention of the resin restoration (Figure 1) (1). This system is widely used among practitioners because it is effective, less technique-sensitive, and results in less post-operative sensitivity (1). The decreased sensitivity is attributed to the intact smear plugs in the dentinal tubules (11, 14). However, it has certain disadvantages, such as containing hydrophilic monomers, which increases the permeability of the hybrid layer (smear layer and adhesive layer), rendering the restoration prone to hydrolysis and chemical decomposition (15).

Figure 1: Selective etching of enamel (1).

The universal adhesive system uses primer and adhesive in a single step, resulting in better wetting and penetration of the adhesive to the etched enamel and dentin; however, it produces a thin adhesive layer, which can result in weak polymerization (11, 16). This weak polymerization reduces bond strength, adhesion, hydrolytic resistance, and durability of the adhesive restoration (17, 18).

Marginal Seal in Adhesive Restorations

The success of an adhesive restoration depends on several factors, including the marginal seal. However, obtaining a complete marginal seal between the restoration and the tooth structure has not been achieved by any adhesive restoration to date due to the presence of leakage (19). There are two types of leakage: clinically detectable and clinically undetectable. Fabianelli et al. (20) defined microleakage as clinically undetectable passage of bacteria, molecules, or fluids between the restorative material and the tooth structure. Microleakage can be measured using staining, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), ionization, radioisotopes, or chemical agents (19).

Microleakage results in the degradation and dissolution of restorative material, marginal staining, and marginal collapse. Such leakage results from the bacteria and hydrogen products present in plaque, which precipitate into the interface between the restoration and the tooth structure (21, 22). The leakage of bacteria reaches the pulp, causing inflammation of the pulp and sensitivity to stimuli and secondary caries, necessitating the replacement of the whole adhesive restoration (21, 22). Whereas the leakage of fluids causes hydrolytic degradation and compromises the adhesive layer, resulting in cuspal deflection and eventually enamel fracture (19).

Microleakage occurs due to thermal contraction, polymerization shrinkage, mechanical stresses, and water sorption of the restoration. The improper adaptation of the adhesive restoration at the tooth structure/restoration interface is considered the main reason for these factors. Additionally, the adhesive material often decreases in volume by 2%, resulting in contraction forces causing marginal gaps and adhesive failures (23, 24). The adhesive failure results in loss of the marginal seal (19). The type of cavity also plays a role in the rate of occurrence of loss of marginal seal. For instance, in a class II cavity, the margin is often at the gingival level, which is accompanied by the loss of enamel, resulting in unstable bonding (19). Additionally, the difference in elastic modulus between the tooth and the restoration, fluid movement in the dentin, incomplete removal of the smear layer, and inefficient infiltration of primer into the collagen fibers can lead to microleakage (19).

The Effect of Thermocycling on Adhesive Materials

The adhesive restoration is subjected to several mechanical and thermal stresses in the oral cavity. The change in temperature, with the difference in the coefficient of thermal expansion between the restoration and the tooth structure, results in marginal percolation, causing loss of marginal seal, leading to microleakage (19). Thermocycling is a laboratory method used to examine the bond strength of the adhesive layer (25). Clinically, the adhesive restoration is subjected to thermocycling resulting from intermittent temperature changes. As a result of thermocycling, the restoration develops a viscoelastic response that results in residual stresses in the polymeric layer (26). These residual stresses lead to debonding of the adhesive layer, loss of marginal seal, and eventually restoration failure (26).

Bakhsh et al. (25) conducted a study and found that the mean gap percentage before being subjected to thermocycling for the two groups of teeth used was 2.22 and 20.55, respectively. After subjecting the two groups to 2600ºC thermocycling, the marginal gaps in the two groups increased significantly. However, after subjecting them to 5200ºC and 10000ºC thermocycling, the marginal gaps decreased significantly (27). The increase in the marginal gap can be attributed to the decrease in the adhesive resin’s thermal coefficient of expansion after being subjected to short periods of thermocycling. In contrast, the decrease in the marginal gap is attributed to the hygroscopic expansion of dental resin that occurred after being subjected to long periods of thermocycling (28).

El-Damanhoury et al. (29) compared five types of universal adhesives to an etch-and-rinse adhesive system and subjected all the samples to thermocycling under the same conditions. They found that the bonding efficacy of all the adhesives, including the control groups, was affected when subjected to thermocycling. Additionally, thermocycling resulted in a significant decrease in the bond strength of the adhesives used (29). Moreover, the bond failures of both universal adhesives and two-step adhesives were more significant in the gingival floor of class II (29). Bond failure results in the breakage of the marginal seal of the restoration, resulting in microleakage.

The Effect of Aging on Adhesive Materials

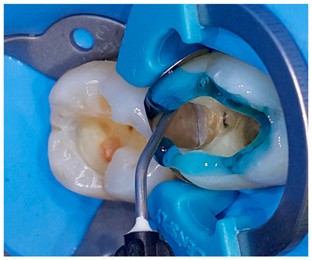

Aging of composite restoration is the chemical, mechanical, biological, and physical processes that the restoration is subjected to over time, resulting in its deterioration and degradation (Figure 2) (30). These factors are extenuated by the behavioral factors of the patient (30).

Figure 2: factors causing the aging of the adhesive restoration (30).

The biological factors include oral health and saliva. The saliva contains multiple enzymes and bacteria; these bacteria bind to the tooth surface and react with the digested carbohydrates, releasing acidic products that dissolve both the dentin and enamel (30). Additionally, the bacteria, mainly Streptococcus mutans, increase the surface roughness of the restoration and adhere more to the composite restorations than to the enamel (30). Whereas enzymes chemically degrade the methacrylate polymers in the matrix of the composite restoration due to their enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis ability (30).

The composite restoration is subjected to several chemical factors in the oral cavity. For instance, artificial saliva increases water sorption of the restoration, filler leachability, and decreases mechanical properties (30). Whereas food and drinks increase the surface roughness, decrease the hardness of the resin composite restoration, reduce the mechanical properties of the restoration, and alter the color of the restoration. Additionally, the rate of consumption of acidic food and drinks significantly affects the mechanical properties of the restoration. When the restoration is subjected to aging in water, its fracture toughness reduces significantly, in addition to a reduction in flexural strength and elastic modulus (30).

The varying physical factors in the oral cavity affect the longevity of the composite restorations. For instance, the temperature in the oral cavity is often 36ºC, with 50ºC marked as the highest temperature and 5°C the lowest (30). Moreover, the teeth are subjected to abrasion, physiological and pathological wear, attrition, and abfraction. These factors cause the wear and degradation of the adhesive restoration as well (30).

The mechanical factors in the oral cavity include the biting force, which ranges between Newtons (N) and 430 N. Although the natural teeth can withstand such high biting loads, the composite restoration reacts differently to these loads and can result in its wear, fracture, and failure (30). The aging of the composite restorations can be tested by a fatigue test (30). The fatigue properties are affected by the type of filler, the silanization of the fillers, and the resin matrix. The fatigue resistance of composite restorations decreases significantly when subjected to water immersion (30). These factors combined result in the aging of the restoration, which directly affects the bonding strength, compromising the marginal seal, leading to the failure of the restoration.

Clinical Implications

Several attempts were made to develop materials used in adhesive dentistry to avoid the failure of the marginal seal and the occurrence of microleakage. Studies are focusing on the development of bioactive compounds with antimicrobial effect and remineralizing properties to prevent the development of secondary caries at the tooth-restoration interface, causing microleakage and restoration failure (31). The development of recurrent caries depends mainly on the patient’s oral hygiene and their eating habits; however, the composite restoration might play a role in their development. An example of these bioactive compounds is chlorohexidine. It is an antimicrobial agent and a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor (31). Some studies suggest the use of chlorohexidine is an additional priming step for demineralized dentin to further enhance the bonding stability and the marginal seal stability (32). Another compound that is used in modern adhesive dentistry is silver nanoparticles, with a concentration of 0.1% to 1% due to their antimicrobial effect and biocompatibility with the tooth structure. It is released from the restoration, exhibiting a good antibacterial effect, decreasing the rate of recurrent caries occurrence (31). Quaternary ammonium compounds are another example of bioactive materials; they are added to monomers, forming quaternary ammonium methacrylates, which are antibacterial compounds and inhibit matrix metalloproteinase, thus preventing adhesive layer failure and marginal seal failure (31).

Conclusion

Adhesive dentistry can be considered the core of dentistry in the modern world. However, several challenges remain due to the differences in properties between the adhesive material used and the tooth structure. Bonding to enamel and dentin and obtaining an optimum marginal seal is a challenging and technique-sensitive procedure. Further research is needed to obtain adhesive materials that can withstand the effects of thermocycling and aging without resulting in adhesive failure, compromising the marginal seal, and resulting in microleakage and restoration failure.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Non applicable.

Data availability

All data are available within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.