Volume 5, Issue 12

December 2025

Influence of Root Canal Sealer Biocompatibility on Periapical Healing

Tariq Hassan Alhazmi, Abdulelah Talal Khawaji, Lulua Ahmed Almuways

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2025.51207

Keywords: Root canal sealer, biocompatibility, periapical healing, periapical lesions, endodontic therapy

Periapical lesions are the result of the colonization of microorganisms around the tooth root and the root canal. Before treatment, periapical lesions must be diagnosed, and endodontic status needs to be assessed. Diagnosis should be confirmed clinically and radiographically. Endodontic therapy involves treatment of root canal infection, cleaning and shaping of the root canals, and filling the root canal space. Root canal sealers play a crucial role in periapical healing by contributing to the hermetic obturation of the root canal system. Various root canal sealers are available with various biocompatibility, cytotoxicity, and physicochemical properties. However, no extensive comparative report on the impact of root canal sealers’ biocompatibility on periapical healing has been reported. This review aims to investigate the role of biocompatibility of different root canal sealers on periapical healing. Root canal sealers can be classified into zinc oxide eugenol-based sealers, zinc oxide-based sealers without eugenol, glass ionomer-based sealers, silicone-based sealers, resin-based sealers, calcium hydroxide-based sealers, and bioceramic sealers. Biocompatible, efficient sealers are those with good antimicrobial properties, good stimulation of tissue regeneration, positive impact on osteoblasts and osteoclasts, and low risk of inducing an inflammatory response. The recently developed bioceramic sealers have been associated with adequate clinical and biological outcomes; however, they have demonstrated potential neurotoxicity. Future studies should investigate the integration of various modifications in the composition of different sealers and their impact on periapical healing.

Introduction

Periapical lesions are very frequent clinical signs of pulpal necrosis and are considered the consequence of the body’s inflammatory response to microorganisms around the tooth root and the root canal, which leads to chronic inflammation (1). The etiology of periapical lesions involves trauma, caries, and tooth wear (1). More specifically, the pathology results in the loss of blood supply of pulp tissue and the colonization of microorganisms, leading to periradicular pathosis (2). Periapical lesions are also associated with previous endodontic treatments and modification of root canal anatomy due to previous treatments, direct trauma, or missed canals (3-5). This condition may present with pain on compression of the tooth, pain on touching the occlusal surface, abscess, or fistula (3-5).

Before treatment, periapical lesions must be diagnosed, and the endodontic status needs to be assessed. Radiographic examination should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and to evaluate the size of the lesion (6). Various classification systems for periapical lesions are available (7-9), with the Peri Apical Indexes system (PAI) being the most frequently used classification (8, 9). Periapical healing is the structural and functional replacement of the bone, which is regulated by an intricate interplay between the osteoclasts and osteoblasts, allowing the bone formation to occur. Notably, this process is significantly influenced by the host’s intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms (10).

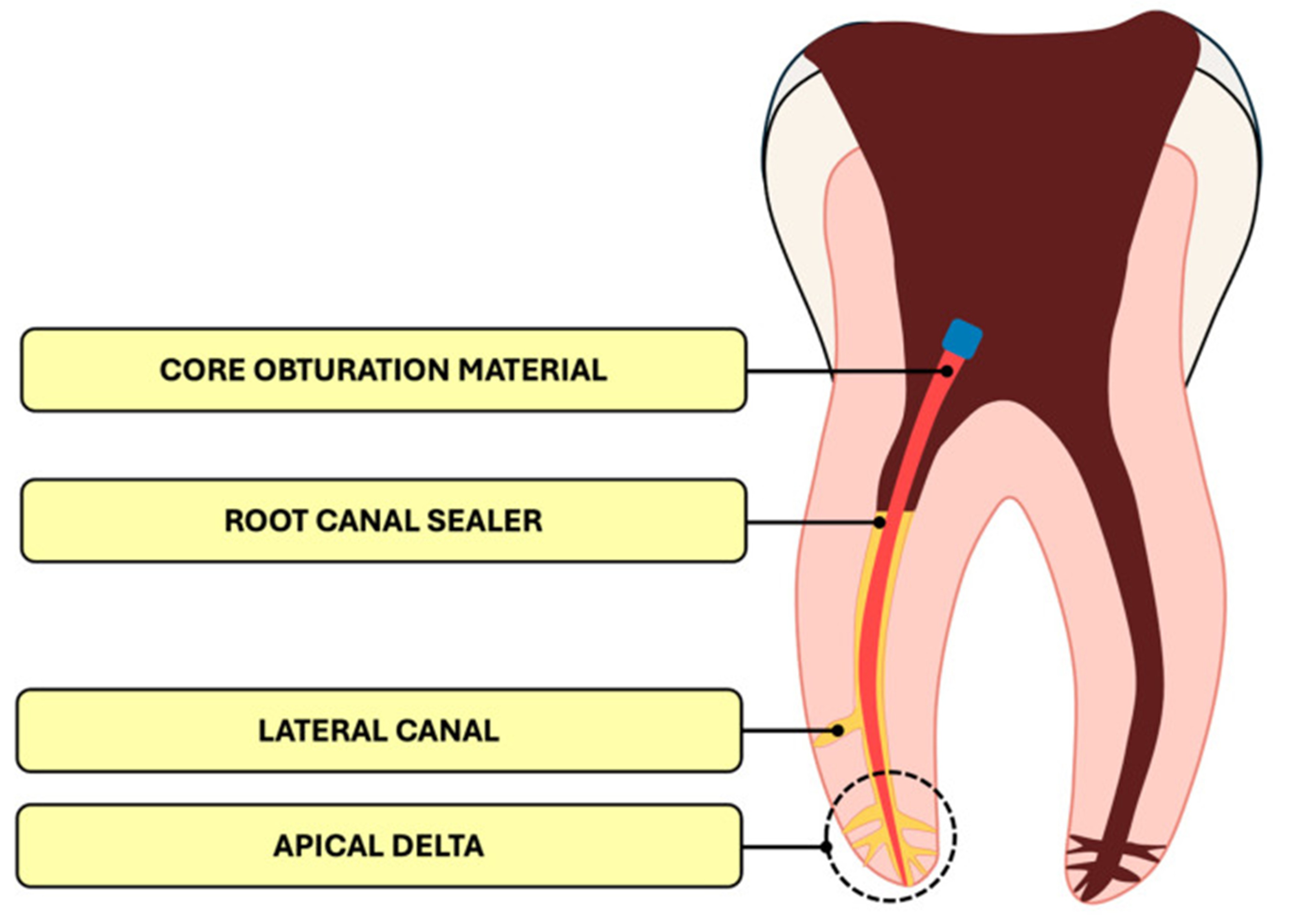

Endodontic therapy involves treatment of root canal infection, cleaning and shaping of the root canals, and filling the root canal space (Figure 1), thus hindering the penetration of microorganisms and fluids at both the coronal and apical ends (11). Successful endodontic treatment relies on proper instrumentation, comprehensive disinfection, and obturation. The synergistic combination of the obturation material and the sealer creates a hermetic seal (12). A root canal sealer should possess adequate biological, physical, and chemical properties (13).

Root canal sealers aid in the hermetic obturation of the root canal system, particularly at the sealer-dentin interface, sealing accessory root canals and dentinal tubules. Different types of root canal sealers with different setting formations are available, including zinc oxide eugenol-, resin-, silicone-, and calcium silicate-based sealers. These sealers have various biological and physicochemical properties, shown in their antimicrobial activity, resistance to irrigating solutions, and long-term dimensional and physicochemical stability within the canal (14), insolubility, and lack of cytotoxicity toward periapical tissues (15). These biological and physicochemical properties can make one sealer superior to another based on the clinical situation.

The cytotoxicity, biocompatibility, cell plasticity, differentiation potential, and bioactive properties of sealers greatly determine their biological interactions with surrounding tissues. Cytotoxicity is defined as the toxic effects of materials on vital tissues (16), while biocompatibility is the degree of compatible and harmless properties of a material to the vital tissues (17). Biocompatible materials are those materials that are not associated with an immunological or toxic response when in contact with the tissue or tissue fluids, resulting in stable host responses during the application (17).

Although multiple studies have investigated the physical, chemical, and biological properties of sealers (2, 11, 18-20), due to their significant influence in endodontic applications, no extensive comparative report on the impact of root canal sealers’ biocompatibility on periapical healing has been reported. The aim of this review is to explore the clinical and biological influence of various root canal sealers on periapical healing, with more focus on the cytotoxicity and biocompatibility of these sealers.

Figure 1: Internal structure of the root canal filling (21).

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in Medline (via PubMed), Scopus, and Web of Science databases up to November 19, 2025. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and relevant free-text keywords were used to identify synonyms. Boolean operators (AND’, OR’) were applied to combine search terms in alignment with guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Key search terms included: “Root canal sealer” AND “Biocompatibility” AND “Periapical healing”. Summaries and duplicates of the found studies were exported and removed by EndNote X8. Any study that discusses the influence of root canal sealer biocompatibility on periapical healing and published in peer-reviewed journals was included. All languages are included. Full-text articles, case series, and abstracts with related topics are included. Case reports, comments, and letters were excluded.

Discussion

An Overview of Root Canal Sealers

Currently, various root canal sealers are available with various chemical compositions, physicochemical properties, biocompatibility, and biological behavior (21, 22). Root canal sealers can be classified into zinc oxide eugenol-based sealers, zinc oxide-based sealers without eugenol, glass ionomer-based sealers, silicone-based sealers, resin-based sealers (including methacrylate and epoxy resin formulations), calcium hydroxide-based sealers, and bioceramic sealers (21). Each type of sealer offers specific advantages while also presenting certain limitations compared to others (Table 1).

Zinc oxide eugenol-based sealers are associated with strong antimicrobial properties (23); however, significant cytotoxicity has been reported for this type of sealer (24). Notably, the antimicrobial properties of these sealers are attributed to the eugenol. Another disadvantage is that they undergo remarkable polymerization shrinkage after being set, leading to the formation of microleakage (25). The material is resorbable if extruded beyond the apical foramen. Glass ionomer sealers also have strong antibacterial properties, as well as minimal shrinkage after setting and greater resistance to vertical root fracture (26). This is attributed to their fluoride content. Ensuring a better seal, they form a chemical bond with dentin (26); however, this strong seal complicates removal from the canal system in cases of endodontic retreatment (27).

Although silicone-based sealers exhibit beneficial physicochemical and mechanical properties, they lack adequate antibacterial properties (28). The favorable physicochemical and mechanical properties of these sealers are attributed to their low viscosity (29), which allows for excellent penetration into the root canal system. Silicone-based sealers are dimensionally stable, insoluble, and non-cytotoxic. When compared with sealers based on glass ionomer, epoxy resin, or calcium hydroxide, methacrylate resin-based sealers have shown superior adhesion to dentin (30). However, they have been associated with the formation of gaps and the presence of residual monomers in cases involving complex root canal anatomy (31). The residual monomer is highly cytotoxic and has also been associated with genotoxic and mutagenic effects (32).

Epoxy-based sealers exhibit high biocompatibility (33), low solubility, and favorable physicochemical properties, such as low polymerization shrinkage (34), good sealing ability, and dimensional stability (35). However, they lead to chronic inflammation when extruded beyond the apical foramen, due to their limited bioactivity and slow resorption. These reactions usually subside over time (33, 36). Calcium hydroxide-based sealers, compared to other sealers, can strongly regenerate tissues, particularly hard tissues, such as bone, dentine, and cementum. These sealers are particularly recommended for cases with large periapical lesions or during retreatment procedures (37). Although they demonstrate superior biocompatibility parameters, they may be less durable in terms of long-term sealing ability (38).

Bioceramic sealers are the most recent type of sealers, characterized by strong periapical tissue regeneration properties, a secure and well-adapted seal within the root canal system (39), post-operative low polymerization shrinkage, and a high adaptation in moist environments (40). Nevertheless, research has suggested possible neurotoxic effects, so extra care is recommended when operating near the inferior alveolar nerve (41). Various modifications have been integrated into currently available sealers, such as the integration of antimicrobial agents such as chlorhexidine, silver, and chitosan.

|

Table 1. Advantages & Disadvantages of Major Sealer Groups |

||

|

Sealer Type |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Zinc oxide eugenol-based sealers |

Strong antimicrobial |

High cytotoxicity; shrinkage |

|

Epoxy Resin sealers |

Gold standard; stable seal |

Slow resorption; possible inflammation |

|

Silicone-based sealers |

Highly biocompatible; stable |

Low antibacterial effect |

|

Methacrylate Resin sealers |

Strong adhesion |

Toxic monomers; gap formation |

|

Calcium Hydroxide sealers |

Bioactive; promotes healing |

Poor long-term sealing |

|

Bioceramic sealers |

Bioactive; excellent seal |

Neurotoxicity risk; difficult retreatment |

Biological impact of sealers’ biocompatibility on periapical healing

The biocompatibility and cytotoxicity of various types of sealers have been assessed by multiple studies (11). Collado-González et al. evaluated the biocompatibility of GuttaFlow2, MTA Fillapex, and GuttaFlow Bioseal sealers and their cytotoxic effects on human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) in vitro (42). GuttaFlow Bioseal sealer (a silicone-based sealer) showed a high proliferation level, cell spreading, and binding. It has also been associated with better cytocompatibility, with additional in vitro and in vivo investigations confirming the suitability for clinical applications (42). In addition, GuttaFlow2 and GuttaFlow Bioseal indicated less cytotoxic character, and the extracts of sealers indicated time- and dose-dependent influences on hPDLSCs. Ferreira et al. also evaluated the cytotoxic response of GuttaFlow Bioseal and compared it with epoxy resin sealer (43). They reported higher biocompatibility with GuttaFlow Bioseal.

Vouzara et al. evaluated the cytotoxic features of a bioceramic calcium silicate endodontic sealer (BioRoot RCS) by comparing its impact on cell viability and proliferation of NIH/3T3 cells with calcium oxide and phosphate-containing epoxy (SimpliSeal) and a mineral trioxide aggregate filler containing salicylate (MTA-Fillapex) resin sealers (44). BioRoot RCS exhibited considerably lower cytotoxicity and was rather cytocompatible compared to the others. SimpliSeal and MTA-Fillapex had significant cytotoxicity (44). The biocompatibility and cytotoxic effects of Sealer Plus (a calcium hydroxide-epoxy resin-containing sealer) were evaluated by Cintra et al., using L929 fibroblasts and the MTT assay. They found that Sealer Plus is less cytotoxic compared to SimpliSeal, AH Plus, and Endofill (45).

Saghiri et al. evaluated the cytotoxicity and dimensional changes of a polyurethane expandable sealer (PES) and compared it with Sure-Seal Root and AH Plus (46). The cytotoxicity measurement was based on L929 fibroblasts and a cell viability assay (MTS), using extracted single-rooted human teeth (46). An advanced choroidal neovascularization model was utilized for evaluating the sealers on angiogenesis, and SEM analysis was utilized for the measurement of the sealer penetration through the dentinal tubules. Results showed that PES was associated with remarkably higher choroidal neovascularization, MTS, and penetration depth (46). It also showed promising results for dentinal tubule adaptation and penetration along with biocompatibility.

Kapralos et al. aimed to evaluate the influence of root canal sealer’s biocompatibility on periapical healing on the biological level by measuring the effects of five different root canal sealers and their eluates on human alveolar osteoblasts as representatives of periapical bone tissue (20). This was done by measuring the effects of sealers’ biocompatibility on the cell proliferation, adhesion, morphology and gene expression of osteoblasts. Human alveolar osteoblasts are key cells in periapical healing; thus, its testing is valuable in evaluating the impact of sealers’ biocompatibility on periapical healing (20). The five root canal sealers tested were: AH Plus (epoxy-resin sealer), Tubli-Seal (zinc oxide–eugenol sealer), RealSeal SE (methacrylate resin sealer), EndoREZ (methacrylate resin sealer), and Apexit Plus (calcium hydroxide–based sealer). They also tested BeeFill as a representative of the gutta-percha material group.

The five sealers showed various morphological, cell proliferation, and adhesion changes in the osteoblasts. Kapralos et al. reported that AH Plus sealer led to good adhesion for alveolar osteoblasts after 3 days and an increase in the cell number over time (20). It also wasn’t associated with a strong initial inflammatory reaction. The RealSeal SE was associated with cytotoxic effects and limited cell survival, which may be attributed to the release of toxic monomers of incompletely polymerized metacrylate (47). Various studies reported initial toxic effects of Apexit Plus, EndoREZ, and Tubli-Seal sealers on the morphology and adhesion of osteoblasts (33, 48); however, the study of Kapralos et al. was the first to show that the cells do not recover from this initial cytotoxic effect, leading to persistent cytotoxicity (20). In the BeeFill Gutta-Percha, apoptotic cells were visible after 3 days; however, osteoblasts recovered over 7–14 days, showing normal morphology and density.

Regarding the gene expression analysis, Apexit® Plus, AH Plus®, and RealSeal SE were associated with increased Caspase 3 expression after 72 hours (20). Caspase 3 is a cysteine protease that, as a component of an enzyme cascade, is involved in the initiation of cell apoptosis (49). Notably, RealSeal SE induced the strongest apoptosis response. Furthermore, histone 3H3 expression, a marker of proliferation, was significantly lower in RealSeal SE and slightly reduced in Apexit Plus, reflecting reduced osteoblast proliferation due to cytotoxic effects (20). According to these findings, AH Plus and BeeFill sealers showed better compatibility compared to EndoREZ, RealSeal SE, and Tubli-Seal sealers, all of which were associated with stronger toxic effects.

Clinical impact of sealer biocompatibility on periapical healing

The assessment of the impact of sealer biocompatibility on periapical healing on a clinical level is critical. AH plus sealer (an epoxy resin-based sealer) has been reported to achieve better periapical healing, which can be attributed to the fact that when an extrusion beyond the apex occurs, macrophages phagocytose them and do not affect periapical healing negatively (50). However, it also has been reported that resin-based sealers that are extruded beyond the apex require more time to resorb, with radiographic visualization taking 10–16 years (51). The influence of calcium hydroxide sealers on periapical healing has also been investigated. It has shown positive effects in teeth with apical periodontitis and in overcoming both anaerobic bacteria and bacterial lipopolysaccharides when used as an intracanal medicament (52). Sealapex (a calcium hydroxide sealer) has shown significantly higher alkalinity and calcium release values when compared to other sealers, including CRCS, APEXIT, and Sealer-26 sealers (53). Conversely, other studies did not support this finding when comparing CRCS and Sealapex, as they found no significant differences over years (54, 55).

Additionally, it has been reported that calcium silicate MTA sealer can block and prevent any apical fluid flow in cases of open root apex, achieving a more stable and durable seal when compared to traditional zinc oxide and calcium oxide containing sealers (2). This bioactive apical barrier is created due to the release of calcium ions and the formation of apatite deposits (56). Moreover, the contact between calcium silicate MTA cements and simulated body fluids leads to the formation of an apatite coating on the surface, and this apatite layer may help enhance biological activity in the periapical bone by promoting barrier formation and stimulating the activation and differentiation of apical cells (57). The percentage of sealer penetration around the canal perimeter has clinical significance because it represents the sealer’s capacity to seal against microorganisms in the dentinal tubules, regardless of the sealer’s depth of penetration (58).

Bioceramics and bioactive sealers have shown effectiveness in minimizing acute inflammatory responses and enhancing the process of periapical healing. However, it has been reported that bioactive sealers are more biocompatible than bioceramic sealers (59, 60). Furthermore, when a bioactive sealer (Bioroot RCS) was compared to an epoxy resin-based sealer (AH Plus) and a zinc oxide eugenol sealer, the bioactive sealer was associated with better outcomes (59).

Clinical Implications

It is critical to investigate the biocompatibility and cytotoxicity of different root canal sealers in order to achieve adequate periapical healing (Figure 2). Currently available sealers have different physiochemical properties that can significantly impact the choice of best treatment for each patient. Among traditional sealers, epoxy-resin sealers (e.g., AH Plus) remains the gold standard and the most widely used. Moreover, the recently developed bioceramic sealers have shown good adhesion, reduced cytotoxicity, and strong antimicrobial properties; however, they have demonstrated potential neurotoxicity.

Figure 2: Cytotoxicity and biocompatibility of root canal sealers (11).

Future Directions

Owing to their bioactivity, compatibility with the moist environment of the root canal, and their capacity to promote tissue regeneration, a shift towards bioceramic/bioactive sealers has been recently observed. However, they have been associated with neurotoxicity in some cases, prompting future research to investigate modifications in the composition of bioceramics. The integration of various modifications in the composition of root canal sealers can be a topic of interest for future research. Agents like chlorhexidine, silver, and chitosan have shown promising antimicrobial properties, which require additional validation through future research. Furthermore, more focus should be directed towards the use of nanotechnology and naturally derived compounds to improve the clinical safety of root canal sealers.

Conclusion

Root canal sealers have various biological and chemical properties that play a crucial role in the healing of periapical lesions. Sealers with better biocompatibility are those with effective seals, adequate antimicrobial properties, and low risk in inducing an inflammatory response. Bioceramic/bioactive root canal sealers have shown good adhesion, reduced cytotoxicity, and strong antimicrobial properties. Future studies should investigate the integration of various modifications in the composition of different sealers and their impact on periapical healing.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Non applicable.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are embedded within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.