Volume 5, Issue 12

December 2025

Full-Mouth Rehabilitation of a 9-Year-Old Child with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Renovascular Hypertension — A Multidisciplinary Approach under General Anesthesia. A Case Report.

Zahra Alhuwayji, Mohammed Alshoraim, Omar AlShahrani, Naif Asiri, Deepa Shetty

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2025.51206

Keywords: Neurofibromatosis Type 1, pediatric dentistry, oral manifestations, renovascular hypertension, general anesthesia, multidisciplinary management

Background: Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by mutations in the NF1 gene located on chromosome 17q11.2, resulting in loss of neurofibromin function and subsequent tumor formation. The condition affects approximately 1 in 3,000 to 4,000 individuals worldwide and is characterized by variable systemic and orofacial manifestations, often appearing in childhood. Beyond its cutaneous and neural features, NF1 may also involve the vascular system; vascular dysplasia or renal-artery stenosis can occur, leading to renovascular hypertension, a serious systemic complication that increases cardiovascular and anesthetic risk. Importantly, oral manifestations may precede cutaneous lesions and can serve as early diagnostic indicators, underscoring the essential role of dental professionals in the early recognition and multidisciplinary management of NF1.

Case Presentation: A 9-year-old boy diagnosed with NF1 presented with bilateral renal-artery stenosis, systemic hypertension, cardiomegaly, and impaired renal function. He was referred for comprehensive dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia because of extensive caries and limited cooperation. Extraoral examination revealed multiple café-au-lait macules, a convex facial profile, and lip incompetence. Intraoral findings included generalized gingival enlargement, delayed eruption of anterior teeth, remaining roots, and multiple carious lesions. Dental treatment involved restorations, pulpotomies, extractions, placement of stainless-steel crowns, and gingival-exposure surgery. Space maintenance was achieved with a Nance appliance in the maxilla and a lip bumper in the mandible. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and follow-up visits demonstrated improved oral hygiene, healthy gingival tissues, and stable restorations.

Conclusion: NF1 poses unique diagnostic and management challenges due to its multisystem involvement and anesthetic considerations, particularly when complicated by renovascular hypertension. Dental practitioners play a pivotal role in identifying oral manifestations, coordinating multidisciplinary medical care, and applying preventive strategies. Early recognition, individualized treatment planning, and structured long-term follow-up are essential to preserve oral health and enhance the quality of life of affected children.

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis comprises a heterogeneous group of genetic syndromes resulting from the inactivation of distinct tumor-suppressor genes. It is classified into eight recognized types, of which Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is the most prevalent (1). NF1, also known as von Recklinghausen’s disease, is a multisystem autosomal-dominant disorder caused by mutations in the NF1 gene located on chromosome 17q11.2. This gene encodes neurofibromin, a tumor-suppressor protein, and loss of its function leads to dysregulated cell growth and tumor formation (2). The global prevalence of NF1 is estimated to be approximately 1 in 3,000 to 4,000 individuals (3).

Neurofibroma, a benign nerve-sheath neoplasm and the predominant feature of NF1, frequently occurs in the head and neck region and may present as solitary or generalized, peripheral or central lesions. Within the oral cavity, the tongue is the most common site of peripheral neurofibromas, often resulting in macroglossia. Other common locations include the lips, mucobuccal fold, gingiva, floor of the mouth, and palate. Enlargement of the fungiform papillae is another commonly reported oral soft-tissue manifestation in NF1. Intraosseous neural lesions of the jaws are rare and appear as central unilocular or multilocular radiolucent areas. Clinically, these lesions may cause anatomical deformities and displacement of adjacent teeth.

Radiographically, NF1 may present with enlargement or ramification of the mandibular canal, thinning and concavity of the ramus, enlargement and inferior positioning of the mandibular foramen, a deepened coronoid notch, increased bone density, decreased mandibular angle, notching of the inferior mandibular border, and hypoplastic coronoid and condylar processes. Compression of cranial nerves by adjacent neurofibromas can produce varying degrees of paresthesia or neuralgia. The most serious complication of NF1 is the increased risk of malignant transformation, most commonly into neurofibrosarcoma, which has also been reported within the oral cavity (4).

Although NF1 is primarily known for its cutaneous and skeletal manifestations, it may also involve visceral and vascular systems. Vascular abnormalities, particularly renal-artery stenosis, can lead to secondary or renovascular hypertension, which significantly increases cardiovascular and anesthetic risk in affected individuals (5, 6). Cardiac findings such as cardiomegaly and vascular dysplasia have also been described as part of the systemic spectrum of NF1, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary medical and dental management. The clinical manifestations of NF1 include cutaneous, oral, and craniofacial alterations. Characteristic cutaneous findings include café-au-lait macules, freckling, and multiple neurofibromas. Oral soft-tissue involvement may manifest as prominent lingual papillae, mucosal or gingival neurofibromas, macroglossia, and gingivitis associated with poor oral hygiene. Craniofacial abnormalities, such as orbital or sphenoidal dysplasia, a shortened mandibular body and ramus, and maxillary hypoplasia, are also characteristic features (7). Oral manifestations further include dental abnormalities such as impacted, displaced, or missing teeth, gingival hyperplasia, and enamel defects such as hypomineralization or hypoplasia (8).

In the present case, the child’s medical profile was further complicated by bilateral renal-artery stenosis, renovascular hypertension, cardiomegaly, and impaired renal function, conditions that increased the anesthetic risk and necessitated multidisciplinary coordination. This report describes the comprehensive dental management of a 9-year-old boy with NF1 and significant systemic involvement who required full-mouth rehabilitation under general anesthesia.

Case Presentation

A 9-year-old boy presented with multiple carious teeth requiring comprehensive dental management. His medical history was significant for Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1), complicated by bilateral renal-artery stenosis, systemic hypertension, impaired left-kidney function following angioplasty, and cardiomegaly. The patient was maintained on long-term antihypertensive therapy (nifedipine), along with aspirin and minoxidil. He had no known drug or food allergies, and his vaccination record was complete and up to date.

The child was born full term with normal developmental milestones; however, growth assessment revealed both height and weight below the 5th percentile according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2000 growth charts (9). Systemic examination revealed multiple café-au-lait macules, mild hirsutism, adenoidal hypertrophy, and bilateral palpebral ptosis (Figure 1). Before dental intervention, multidisciplinary medical clearance was obtained from pediatric medicine, nephrology, cardiology, hematology, and neurology to ensure suitability for general anesthesia (GA).

Extraoral findings included a convex facial profile, Angle Class II malocclusion (10), and lip incompetence. Intraoral examination revealed generalized plaque accumulation, gingival hypertrophy, remaining roots, and delayed eruption of teeth #52, #51, #62, and #72, accompanied by mild malpositioning (Figure 2). Oral hygiene was rated as fair using the Simplified Greene and Vermillion Plaque Index, with a calculated score of 1.5 (9/6) (11). No intraoral neurofibromas or ulcerations were observed. Gingival enlargement was attributed to the underlying genetic disorder (gingival disease associated with NF1) (12).

The patient exhibited a high-caries and periodontal-risk profile, Angle Class II malocclusion with increased overjet and anterior open bite (10), and nutritional deficiencies related to limited grain intake and frequent consumption of cariogenic snacks.

A comprehensive full-mouth rehabilitation was planned under GA due to the child’s extensive dental needs, systemic complexity, and limited cooperation. The behavior-management phase began with behavioral assessment and individualized strategies. Based on the Frankl Behavior Rating Scale, the patient scored 2 (Negative), indicating fearful behavior (13). According to Wright’s Classification of Cooperative Behavior, he was potentially cooperative but tense (14), with an attention span of approximately 20 minutes. The Tell–Show–Do and positive reinforcement techniques were applied following the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) behavior guidance guidelines (13).

Under GA, the following dental procedures were completed: restorations of multiple primary and permanent molars; pulpotomies followed by stainless-steel crown placement; extractions of non-restorable and retained teeth; gingival-exposure surgeries for unerupted anterior teeth (#52, #51, #62, #72); oral prophylaxis; and topical fluoride application (Figures 3–5). Hemostasis was achieved successfully, and no intraoperative complications occurred.

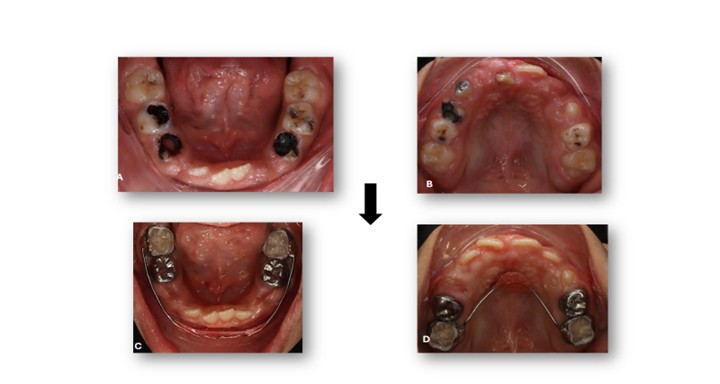

At the one-week postoperative review, healing was satisfactory, with no signs of infection or discomfort. Two weeks later, a multidisciplinary consultation among pediatric dentistry, orthodontics, and periodontics was conducted. Interceptive orthodontic treatment was initiated using a Nance appliance in the upper arch to preserve space and prevent mesial drift of posterior teeth, and a lip bumper in the lower arch to reduce lip pressure and support arch development (Figure 6). A lingual holding arch was planned for subsequent placement following the full eruption of the lower permanent teeth.

The patient was also referred to a nutritionist for dietary modification appropriate for his renal condition and hypertension management. A recall schedule was established every three months, with radiographic evaluations every six months, given his high-caries risk and systemic involvement. Each recall visit included evaluation of restorations and crowns, monitoring of tooth eruption and occlusal development, professional prophylaxis, topical fluoride application, and reinforcement of oral hygiene and dietary practices.

At subsequent follow-ups, restorations remained stable, gingival health improved, and no new carious lesions were observed (Figure 7). The patient’s behavior and cooperation improved markedly, attributed to pain relief and the establishment of trust. Continuous reinforcement of oral-hygiene techniques and dietary counseling was emphasized at each visit.

Figure 1: Clinical and intraoral photographs of the patient demonstrating characteristic manifestations of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. A) Frontal facial view showing bilateral palpebral ptosis (white arrows). B) Full-body view revealing multiple café-au-lait macules distributed over the trunk and upper limbs. C) Maxillary occlusal view exhibiting generalized gingival enlargement, delayed eruption of permanent teeth, and multiple carious lesions affecting the primary molars. The palatal mucosa appears thickened, with hyperplastic gingival tissue partially covering the crowns. D) Right lateral intraoral view displaying Angle Class II malocclusion, partially erupted maxillary incisors, and gingival enlargement extending into the buccal vestibule.

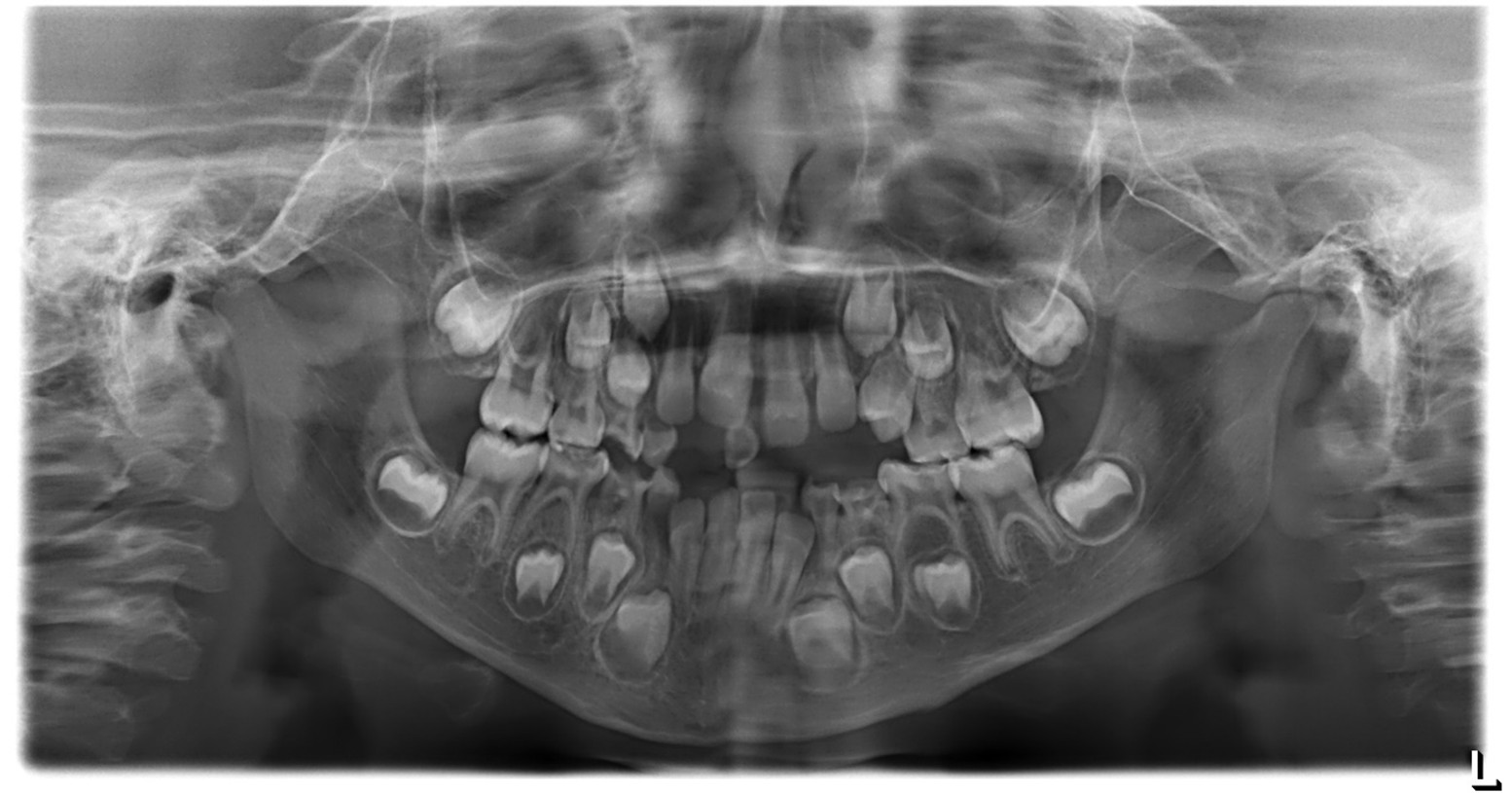

Figure 2: Panoramic radiograph (OPG). According to the AAPD Guidelines for Prescribing Dental Radiographs, for a new patient in the mixed dentition stage being evaluated for dental disease and development, an individualized radiographic examination should include a panoramic radiograph with posterior bitewings and/or selected periapical views. The present panoramic image shows a straight nasal septum with normal nasal passages, intact maxillary sinuses, and symmetrical right and left condyles. The inferior border of the mandible appears intact, and the bone trabecular pattern is normal. The patient’s dental age corresponds approximately to the chronological age, with a complete complement of teeth and no supernumerary teeth. No pathological or structural abnormalities were detected.

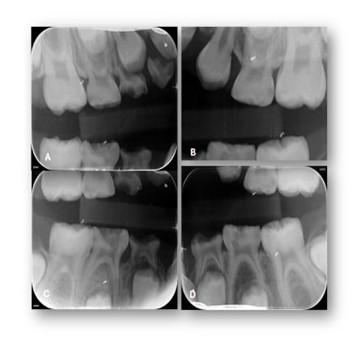

Figure 3: Selected periapical radiographs. A-D) According to the AAPD Guidelines for Prescribing Dental Radiographs, when evaluating a new patient in the mixed-dentition stage for dental disease and developmental assessment, an individualized radiographic examination should include a panoramic radiograph supplemented by posterior bitewings and selected periapical images as indicated.

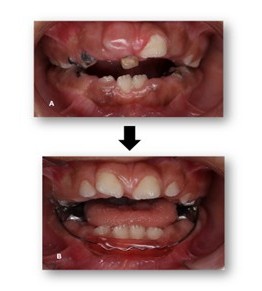

Figure 4: Pre- and post-operative records. A) Pre-operative intraoral view showing extensive caries and severe breakdown of tooth structure. B) Post-operative view demonstrating gingival exposure of the anterior teeth and improved oral condition following treatment.

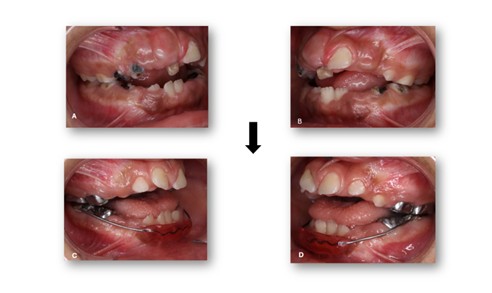

Figure 5: Pre- and Post-Operative Records. Intraoral lateral views. A, B) Pre-operative views showing severe caries and tooth structure breakdown. C, D) Post-operative views showing restored teeth and improved occlusal condition.

Figure 6: Pre- and Post-Operative Records. Intraoral occlusal photographs. A, B) Pre-operative views showing extensive caries and tooth structure breakdown. C, D) Post-operative views showing restored teeth and improved oral condition with placement of a Nance appliance in the upper arch and a lip bumper in the lower arch.

Figure 7: Post-Operative Selected periapical and bitewings radiographs. A-D) Post-operative views showing restored teeth, resolution of carious lesions, and improved periapical status following treatment.

Discussion

This case adds valuable insight into the oral and systemic manifestations of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) in pediatric patients and reinforces established clinical observations in literature. The child presented with café-au-lait macules, gingival enlargement, delayed tooth eruption, and malocclusion, features consistent with those described by Sigillo et al. (4) and Buchholzer et al. (7). These studies emphasized that craniofacial and dental alterations can precede the development of neurofibromas, highlighting the diagnostic importance of early dental evaluation in children suspected of having NF1. Such early recognition is critical because dentists may be the first clinicians to identify subtle signs that warrant further medical investigation.

The oral findings presented in this report also align with the age-dependent manifestations described by Thota et al. (1), who reported delayed eruption patterns and enamel alterations in pediatric NF1 patients. The current case mirrors these developmental disturbances, underscoring the need for continuous dental follow-up throughout childhood and adolescence. The generalized gingival overgrowth observed is similarly consistent with the soft-tissue changes reported by Wotjiuk et al. (15), who underscored the risk of intraoperative bleeding from dysplastic or hypervascular vessels within neurofibromas. Additional literature further expands these observations; Cherifi et al. (16) documented mucosal neurofibromas, periodontal dysfunction, and craniofacial asymmetry, while Cervellera et al. (17) reported developmental anomalies such as supernumerary teeth, demonstrating the spectrum of oral presentations associated with NF1.The child’s systemic profile, bilateral renal-artery stenosis, cardiomegaly, and hypertension—illustrate the vascular complications associated with NF1. Bashiri et al. (18,19) emphasized that such visceral involvement elevates both medical and anesthetic risks, necessitating comprehensive, multidisciplinary coordination before any invasive procedure. The vascular pathology described by Duan et al. (20) further supports these observations, as renal-artery stenosis is a well-documented yet underrecognized manifestation of NF1 that can appear early in life. In accordance with this body of evidence, extensive preoperative assessment was performed by nephrology, cardiology, hematology, neurology, and pediatric medicine to ensure that general anesthesia could be safely administered.

The successful completion of full-mouth rehabilitation under general anesthesia in this case parallels the outcomes reported by Wotjiuk et al. (15), demonstrating that a single, comprehensive treatment approach can yield favorable functional and behavioral results in medically complex pediatric patients. The patient’s postoperative improvement in oral hygiene, comfort, and cooperation further supports the value of multidisciplinary, behaviorally sensitive, and preventive dental care in NF1 management.

Taken together, findings from this case and previously published literature underscore that oral manifestations in NF1 can serve as important early indicators of the disease and may reflect underlying systemic involvement. Regular dental follow-up, preventive strategies, and close coordination with medical specialists are essential to optimizing both oral and overall health outcomes. Future multicenter studies are needed to better define long-term dental, surgical, and anesthetic outcomes in pediatric NF1 patients, particularly those presenting with complex craniofacial or cardiovascular involvement.

Conclusion

This case underscores the importance of recognizing oral manifestations as potential early indicators of systemic disease in children with complex medical conditions. The coexistence of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 with renovascular hypertension and cardiomegaly presented unique diagnostic and anesthetic challenges that required a multidisciplinary approach. Comprehensive dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia allowed safe and effective management while improving oral function, hygiene, and behavior. The case highlights how timely dental intervention and interprofessional coordination can significantly enhance the quality of life and clinical outcomes in medically compromised pediatric patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Ahmed Alasmari from the Department of Orthodontics and Dr. Ahmed Alshbab from the Department of Periodontics for their expert opinions and clinical consultations. The authors further acknowledge the Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Armed Forces Hospital, Southern Region, Khamis Mushait, Saudi Arabia, for their continuous assistance and collaboration during the management of this case.

Disclosure

Statement

The authors declare that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Furthermore, the authors confirm that they have no relevant affiliations, financial interests, or personal relationships that could have influenced the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors affirm that they have no financial relationships, either current or within the past three years, with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Ethical Consideration

Informed consent for both treatment and open-access publication of this case report was obtained or appropriately waived from all relevant participants, in accordance with institutional and ethical guidelines.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included within the manuscript and available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Zahra Alhuwyji and Mohammed Alshoraim contributed to the conceptualization of the report and data collection, while Zahra A.Alhuwayji was primarily responsible for drafting and writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version prior to submission.