Volume 1, Issue 2

May 2021

Knowledge of Dental Students and Dentists Towards Dental Ethics in Riyadh City: A Cross-Sectional Study

Ruba Al-Mutlaq, Basmah Al-Feraih, Hayat Al-Aidroos, Hiba Al-Neema, Rana Al-Asmari, Rinad Al-Balawi, Abdulrahman Al-Saffan

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2021.1105

Keywords: Dental ethics, ethics and professionalism, code of ethics, dentist, dental students, practical knowledge, Saudi Arabia

Background: Ethics encompasses moral conduct and judgment. The typical expectation of any dental practitioner to benefit society & humanity and to provide the best ethical attitude towards their patients. There are five ethical components: autonomy (self-governess), non-malfeasance (do no harm), beneficence (do good), justice (fairness), veracity (truthfulness). This study aims to evaluate dental student and dental practitioner knowledge of dental ethics at dental schools in Riyadh city.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study of dental students and dentists from different dental schools in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. The study populations encompassed dental students and dentists in Riyadh City, to a total of 625 individuals. A questionnaire was utilized to address the five main components of ethics. It was approved by the institutional review board of Riyadh Elm University.

Results: A total of 625 participants were included in the study and of these, 67.5% (n= 422) were female. Only education year (P-value= 0.002), and university (P-value= 0.042) were significant predictors of the participant's awareness of the Hippocratic oath. Meanwhile, gender (P-value= 0.004), and university (P-value< 0.001) were the significant predictors of the participants’ knowledge of the non-maleficence (do no harm) concept.

Conclusion: Most of the participants were unaware of the five ethical components. Dentists and dental students should know more about these principles. More courses and workshops are recommended to provide sufficient knowledge on ethical components among dental students.

Introduction

The word ‘ethics’ is derived from the Greek word ‘Ethos’, which means custom or character. It is defined as a part of philosophy that deals with moral conduct and judgment (1). A study of good and evil, right and wrong, and duty and obligation (2). As the twenty-first century began, attention was increasingly paid to ethics (3). The typical expectation of any dental practitioner is to benefit society and humanity (4). Ethical codes differ between and from one country to another. However, there are many similarities between them. In 1997 the World Dental Federation (FDI) adopted the International Principles of Ethics for the Dental Profession for dentists everywhere (5). There is also an unwritten code of conduct that encompasses professional conduct and judgment (3). One of the most significant challenges for dentists in the clinic context is ethical problems (6). Dentists should be aware of their obligation and responsibility to prevent unwanted events, for example, legal issues (1). Dentists and other health professionals are bound to take the Hippocratic oath, which binds them to fulfill their ethical responsibilities towards their patients (7).

There are five ethical components that all dental students should know: autonomy (self-governess), is the first principle. This is followed by individual liberty and personal self-determination; non-malfeasance, an obligation to avoid harm intentionally and protect the patient from harm); beneficence (do good), an obligation to benefit others without harming yourself; and justice (fairness), inevitably required when addressing dignity, veracity, and sustainability (8).

Veracity is a truthful communication without deception that maintains intellectual integrity (5). It is the responsibility of each dental student to recognize and read all the codes of ethics (1). The teaching of morality and ethics is unique to people from different cultural, socioeconomic, and geographical backgrounds (9). Dentists and dental students are facing ethical matters or problems in in their daily practice (10). To solve an ethical dilemma in dentistry, it is crucial to have studied ethics in an undergraduate curriculum syllabus (11). However, it is voluntary and accountable from the dentist and is not forced by the law. This study aims to evaluate the knowledge of dental students and dentists regarding dental ethics at the dental schools in Riyadh.

Methodology

This is a cross-sectional study that used a pre-structured questionnaire from previous studies to assess ethical jurisprudence among dental practitioners (1, 12). The study populations encompassed dental students and dental practitioners in Riyadh city in Saudi Arabia with an origin sample size of 1,200 participants that was determined based on a sample size calculation with confidence level of 95%. We included all dental practitioners, dental interns, sixth year dental students and fifth year dental students. In addition, only participants from Riyadh city were included. We excluded any dental practitioner, intern or student that was outside Riyadh city or those who did not agree to participate. The survey included questions related to demographics, including age, gender and education level. Recruitment was done by using various colleague contacts, social media, whatsapp groups and in-person discussions. The survey was distributed with a pre-specified link using Surveymonkey website. The data was then exctracted from the site and analyzed using SPSS version 20. The online survey included a short introductory message describing the purpose of the study and stressing voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the right to refuse participatation. Consent was obtained by asking participants to confirm that they agreed to complete the questionnaire by marking a "Yes, I agree to participate” box. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Riyadh Elm Univesity and the study proposal was registered in the research center under the registration number FUGRP/2018/215. Cross-tabulation was achieved using chi-square tests to compare the study group based on age, gender, and education levels. The value of significance was p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the included participants

A total of 625 participants were included in the study, of which 67.5% (n= 422) were females. Most of the participants (70.6%) were aged 20-25 years, followed by 26-30 years (18.6%) and 31-35 years (5.6%). Only 21% (n= 131) of the participants were graduate dentists, 22.4% (n= 140) were sixth year students, 19.2% (n= 120) were interns and the rest were either fourth or fifth year students. Riyadh Elm University had the highest number of contributors (37.4%), followed by King Saud University (21.3%), Al-Farabi Medical Colleges (16.3%), and King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (9.6%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Distribution of the study participants (n=625) |

|||

|

Characteristics |

n |

% |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

203 |

32.5% |

|

Female |

422 |

67.5% |

|

|

Age |

20-25 |

441 |

70.6% |

|

26-30 |

116 |

18.6% |

|

|

31-35 |

35 |

5.6% |

|

|

Above 35 |

33 |

5.2% |

|

|

Education |

4th year |

117 |

18.7% |

|

5th year |

117 |

18.7% |

|

|

6th year |

140 |

22.4% |

|

|

Intern |

120 |

19.2% |

|

|

Dentist |

131 |

21.0% |

|

|

University |

REU |

234 |

37.4% |

|

KSU |

133 |

21.3% |

|

|

PNU |

53 |

8.5% |

|

|

DAU |

43 |

6.9% |

|

|

Al Farabi |

102 |

16.3% |

|

|

KSUHS |

60 |

9.6% |

|

|

DAU: Dar Al Uloom University, KSU: King Saud University, KSUHS: King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, PNU: Princess Nourah University, REU: Riyadh Elm University |

|||

Acquiring the knowledge of bioethics

Lectures or seminars were identified as the most common source of the acquisition of bioethics knowledge (42.2%), followed by training (30.1%), experience at work (19.0%), one’s own reading (5.8%), and other sources (2.9%) (Figure 1). Gender, age groups, education years, and university were all significant predictors of the source used to acquire the knowledge of bioethics (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Association between demographic variables and Acquiring the knowledge of Bioethics |

||||||||||||

|

Demographic variables |

During training |

Experience at work |

lectures / seminar |

one own reading |

others |

p-value |

||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

70 |

37.2% |

46 |

38.7% |

63 |

23.9% |

20 |

55.6% |

4 |

22.2% |

0.000* |

|

Female |

118 |

62.8% |

73 |

61.3% |

201 |

76.1% |

16 |

44.4% |

14 |

77.8% |

||

|

Age |

20-25 |

126 |

67.0% |

76 |

63.9% |

208 |

78.8% |

22 |

61.1% |

9 |

50.0% |

0.000* |

|

26-30 |

40 |

21.3% |

19 |

16.0% |

40 |

15.2% |

13 |

36.1% |

4 |

22.2% |

||

|

31-35 |

9 |

4.8% |

15 |

12.6% |

6 |

2.3% |

1 |

2.8% |

4 |

22.2% |

||

|

Above 35 |

13 |

6.9% |

9 |

7.6% |

10 |

3.8% |

0 |

0.0% |

1 |

5.6% |

||

|

Education |

4th year |

36 |

19.1% |

13 |

10.9% |

61 |

23.1% |

4 |

11.1% |

3 |

16.7% |

0.000* |

|

5th year |

29 |

15.4% |

27 |

22.7% |

56 |

21.2% |

3 |

8.3% |

2 |

11.1% |

||

|

6th year |

42 |

22.3% |

19 |

16.0% |

69 |

26.1% |

10 |

27.8% |

0 |

0.0% |

||

|

Intern |

35 |

18.6% |

26 |

21.8% |

43 |

16.3% |

11 |

30.6% |

5 |

27.8% |

||

|

Dentist |

46 |

24.5% |

34 |

28.6% |

35 |

13.3% |

8 |

22.2% |

8 |

44.4% |

||

|

University |

REU |

75 |

39.9% |

52 |

43.7% |

82 |

31.1% |

21 |

58.3% |

4 |

22.2% |

0.000* |

|

KSU |

34 |

18.1% |

17 |

14.3% |

73 |

27.7% |

7 |

19.4% |

2 |

11.1% |

||

|

PNU |

21 |

11.2% |

8 |

6.7% |

23 |

8.7% |

0 |

0.0% |

1 |

5.6% |

||

|

DAU |

14 |

7.4% |

9 |

7.6% |

14 |

5.3% |

2 |

5.6% |

4 |

22.2% |

||

|

Al Farabi |

34 |

18.1% |

25 |

21.0% |

32 |

12.1% |

5 |

13.9% |

6 |

33.3% |

||

|

KSUHS |

10 |

5.3% |

8 |

6.7% |

40 |

15.2% |

1 |

2.8% |

1 |

5.6% |

||

|

*Chi-square statistically significant, DAU: Dar Al Uloom University, KSU: King Saud University, KSUHS: King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, PNU: Princess Nourah University, REU: Riyadh Elm University |

||||||||||||

Awareness of Hippocratic oath

Most of the participants (61.8%) reported being aware of the Hippocratic oath, while 38.2% reported the opposite (Figure 2). Only education year (P-value= 0.002), and university (P-value= 0.042) were the significant predictors of the participant's awareness of the Hippocratic oath (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Demographic variables and awareness of Hippocratic oath |

||||||

|

Demographic variables |

Aware |

Unaware |

p-value |

|||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

117 |

30.3% |

86 |

36.0% |

0.141 |

|

Female |

269 |

69.7% |

153 |

64.0% |

||

|

Age |

20-25 |

285 |

73.8% |

156 |

65.3% |

0.063 |

|

26-30 |

68 |

17.6% |

48 |

20.1% |

||

|

31-35 |

18 |

4.7% |

17 |

7.1% |

||

|

ABOVE 35 |

15 |

3.9% |

18 |

7.5% |

||

|

Education |

4th year |

78 |

20.2% |

39 |

16.3% |

0.002* |

|

5th year |

67 |

17.4% |

50 |

20.9% |

||

|

6th year |

101 |

26.2% |

39 |

16.3% |

||

|

Intern |

75 |

19.4% |

45 |

18.8% |

||

|

Dentist |

65 |

16.8% |

66 |

27.6% |

||

|

University |

REU |

139 |

36.0% |

95 |

39.7% |

0.042* |

|

KSU |

76 |

19.7% |

57 |

23.8% |

||

|

PNU |

43 |

11.1% |

10 |

4.2% |

||

|

DAU |

27 |

7.0% |

16 |

6.7% |

||

|

Al Farabi |

67 |

17.4% |

35 |

14.6% |

||

|

KSUHS |

34 |

8.8% |

26 |

10.9% |

||

|

*Chi-square statistically significant, DAU: Dar Al Uloom University, KSU: King Saud University, KSUHS: King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, PNU: Princess Nourah University, REU: Riyadh Elm University |

||||||

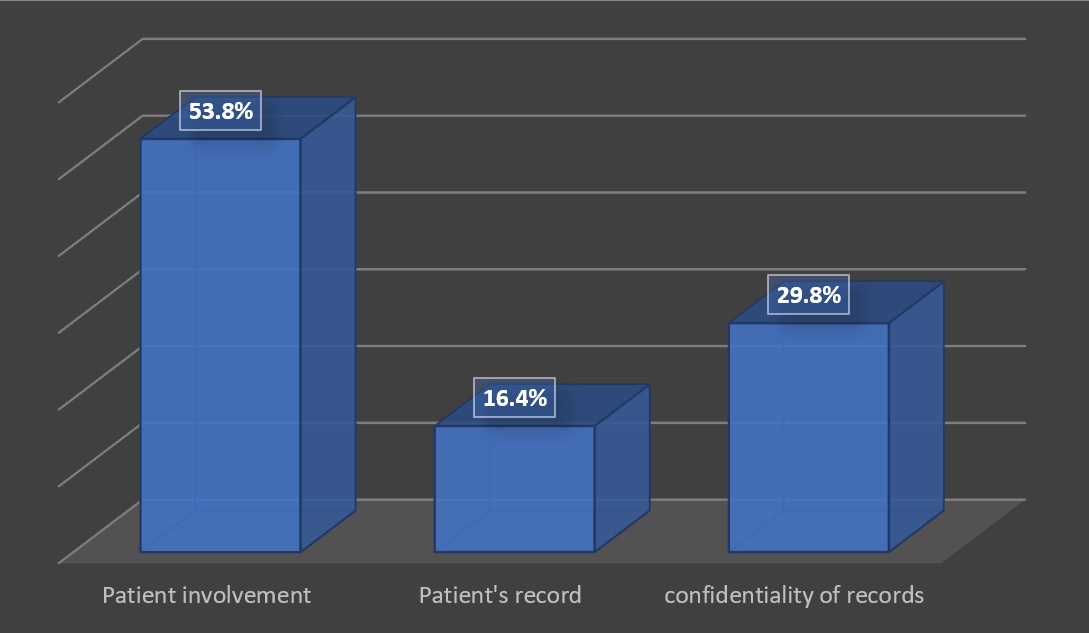

Self-governance (Autonomy)

When considering the participants’ knowledge of the concept of self-governance, patient involvement was the highest reported variable (53.8%), followed by the confidentiality of records (29.8%) and patients’ records (16.5%) (Figure 3). Only age (P-value= 0.024), and university (P-value< 0.001) were significant predictors of the participants’ knowledge of the concept of self-governance (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Demographic variables and Self-governance (Autonomy) |

||||||||

|

Demographic variables |

Patient involvement |

Patient's record |

confidentiality of records |

p |

||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

109 |

32.4% |

39 |

37.9% |

55 |

29.6% |

0.353 |

|

Female |

227 |

67.6% |

64 |

62.1% |

131 |

70.4% |

||

|

Age |

20-25 |

251 |

74.7% |

72 |

69.9% |

118 |

63.4% |

0.024* |

|

26-30 |

53 |

15.8% |

22 |

21.4% |

41 |

22.0% |

||

|

31-35 |

15 |

4.5% |

2 |

1.9% |

18 |

9.7% |

||

|

Above 35 |

17 |

5.1% |

7 |

6.8% |

9 |

4.8% |

||

|

Education |

4th year |

69 |

20.5% |

16 |

15.5% |

32 |

17.2% |

0.146 |

|

5th year |

71 |

21.1% |

18 |

17.5% |

28 |

15.1% |

||

|

6th year |

74 |

22.0% |

28 |

27.2% |

38 |

20.4% |

||

|

Intern |

59 |

17.6% |

24 |

23.3% |

37 |

19.9% |

||

|

Dentist |

63 |

18.8% |

17 |

16.5% |

51 |

27.4% |

||

|

University |

REU |

102 |

30.4% |

48 |

46.6% |

84 |

45.2% |

0.000* |

|

KSU |

78 |

23.2% |

16 |

15.5% |

39 |

21.0% |

||

|

PNU |

41 |

12.2% |

2 |

1.9% |

10 |

5.4% |

||

|

DAU |

18 |

5.4% |

11 |

10.7% |

14 |

7.5% |

||

|

Al Farabi |

46 |

13.7% |

26 |

25.2% |

30 |

16.1% |

||

|

KSUHS |

51 |

15.2% |

0 |

0.0% |

9 |

4.8% |

||

|

*Chi-square statistically significant, DAU: Dar Al Uloom University, KSU: King Saud University, KSUHS: King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, PNU: Princess Nourah University, REU: Riyadh Elm University |

||||||||

Non-maleficence (do no harm)

Regarding participants’ knowledge non-maleficence concept, the consultation referral was the most reported (42.6%), followed by education (19.8%), exposure to a blood-borne pathogen (13.8%), use of auxiliary personnel ability to practice (12.5%), and personal relationships with the patient (11.4%) (Figure 4). Only gender (P-value= 0.004), and university (P-value< 0.001) were the significant predictors of the participants’ knowledge of the non-maleficence (do no harm) concept (Table 5).

|

Table 5: Demographic variables and Non-maleficence (do no harm) |

||||||||||||

|

Demographic variables |

Education |

Consultation referral |

Use of auxiliary personnel Ability to practice |

Exposure to blood-borne pathogen |

Personal relationship with patient |

p-value |

||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

46 |

37.1% |

81 |

30.5% |

21 |

26.9% |

20 |

23.3% |

35 |

49.3% |

0.004* |

|

Female |

78 |

62.9% |

185 |

69.5% |

57 |

73.1% |

66 |

76.7% |

36 |

50.7% |

||

|

Age |

20-25 |

87 |

70.2% |

202 |

75.9% |

57 |

73.1% |

53 |

61.6% |

42 |

59.2% |

0.080 |

|

26-30 |

28 |

22.6% |

41 |

15.4% |

13 |

16.7% |

19 |

22.1% |

15 |

21.1% |

||

|

31-35 |

3 |

2.4% |

13 |

4.9% |

5 |

6.4% |

6 |

7.0% |

8 |

11.3% |

||

|

Above 35 |

6 |

4.8% |

10 |

3.8% |

3 |

3.8% |

8 |

9.3% |

6 |

8.5% |

||

|

Education |

4th year |

17 |

13.7% |

62 |

23.3% |

12 |

15.4% |

14 |

16.3% |

12 |

16.9% |

0.053 |

|

5th year |

24 |

19.4% |

46 |

17.3% |

18 |

23.1% |

14 |

16.3% |

15 |

21.1% |

||

|

6th year |

31 |

25.0% |

62 |

23.3% |

21 |

26.9% |

17 |

19.8% |

9 |

12.7% |

||

|

Intern |

25 |

20.2% |

55 |

20.7% |

14 |

17.9% |

14 |

16.3% |

12 |

16.9% |

||

|

Dentist |

27 |

21.8% |

41 |

15.4% |

13 |

16.7% |

27 |

31.4% |

23 |

32.4% |

||

|

University |

REU |

60 |

48.4% |

93 |

35.0% |

28 |

35.9% |

30 |

34.9% |

23 |

32.4% |

0.000* |

|

KSU |

19 |

15.3% |

58 |

21.8% |

14 |

17.9% |

20 |

23.3% |

22 |

31.0% |

||

|

PNU |

8 |

6.5% |

22 |

8.3% |

7 |

9.0% |

9 |

10.5% |

7 |

9.9% |

||

|

DAU |

5 |

4.0% |

17 |

6.4% |

7 |

9.0% |

9 |

10.5% |

5 |

7.0% |

||

|

Al Farabi |

29 |

23.4% |

32 |

12.0% |

16 |

20.5% |

12 |

14.0% |

13 |

18.3% |

||

|

KSUHS |

3 |

2.4% |

44 |

16.5% |

6 |

7.7% |

6 |

7.0% |

1 |

1.4% |

||

|

DAU: Dar Al Uloom University, KSU: King Saud University, KSUHS: King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, PNU: Princess Nourah University, REU: Riyadh Elm University |

||||||||||||

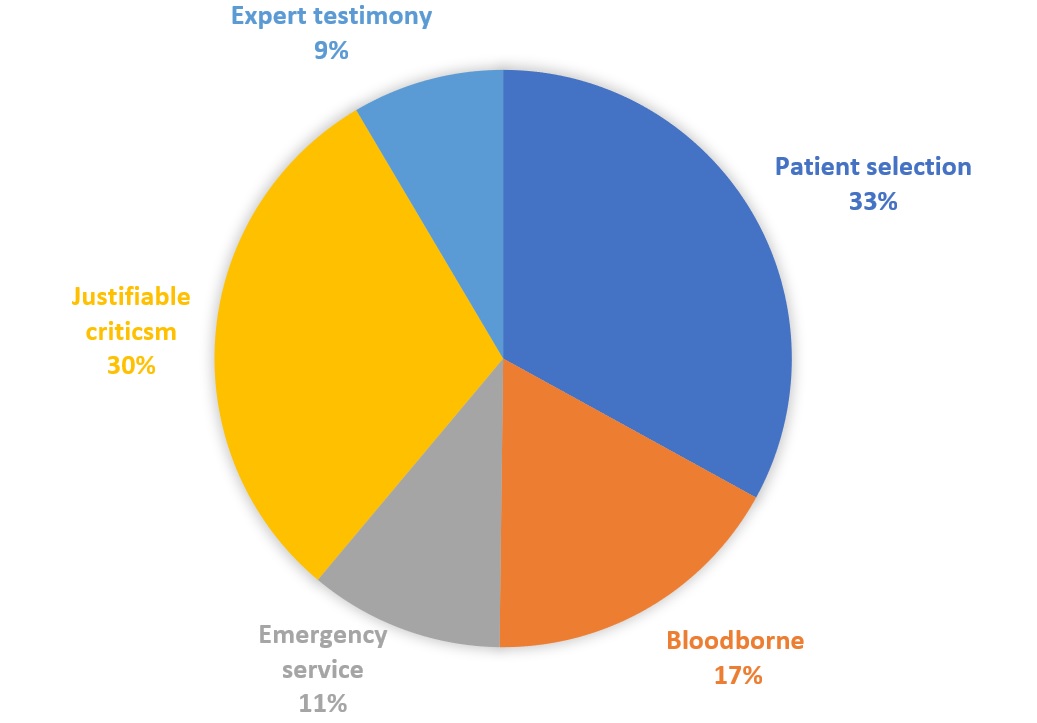

Fairness

Patient involvement was the most reported aspect of the participants’ knowledge of the fairness principle (33.0%), followed by justifiable criticism (30.4%), blood-borne (17.2%), emergency service (10.9%) and expert testimony (8.5%) (Figure 5). Gender (P-value= 0.004), age (P-value= 0.001), education year (P-value= 0.043) and university (P-value< 0.001) were all significant predictors of the participants’ knowledge of the fairness principle (Table 6).

|

Table 6. Demographic variables and Fairness |

||||||||||||

|

Demographic variables |

Patient selection |

Blood borne |

Emergency service |

Justifiable criticism |

Expert testimony |

p-value |

||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

59 |

28.6% |

41 |

38.0% |

30 |

44.1% |

53 |

27.9% |

20 |

37.7% |

0.049* |

|

Female |

147 |

71.4% |

67 |

62.0% |

38 |

55.9% |

137 |

72.1% |

33 |

62.3% |

||

|

Age |

20-25 |

152 |

73.8% |

81 |

75.0% |

50 |

73.5% |

129 |

67.9% |

29 |

54.7% |

0.001* |

|

26-30 |

37 |

18.0% |

20 |

18.5% |

15 |

22.1% |

33 |

17.4% |

11 |

20.8% |

||

|

31-35 |

12 |

5.8% |

4 |

3.7% |

2 |

2.9% |

14 |

7.4% |

3 |

5.7% |

||

|

ABOVE 35 |

5 |

2.4% |

3 |

2.8% |

1 |

1.5% |

14 |

7.4% |

10 |

18.9% |

||

|

Education |

4th year |

45 |

21.8% |

22 |

20.4% |

15 |

22.1% |

24 |

12.6% |

11 |

20.8% |

0.043* |

|

5th year |

41 |

19.9% |

19 |

17.6% |

10 |

14.7% |

37 |

19.5% |

10 |

18.9% |

||

|

6th year |

53 |

25.7% |

20 |

18.5% |

13 |

19.1% |

42 |

22.1% |

12 |

22.6% |

||

|

Intern |

30 |

14.6% |

29 |

26.9% |

17 |

25.0% |

41 |

21.6% |

3 |

5.7% |

||

|

Dentist |

37 |

18.0% |

18 |

16.7% |

13 |

19.1% |

46 |

24.2% |

17 |

32.1% |

||

|

University |

REU |

74 |

35.9% |

42 |

38.9% |

26 |

38.2% |

72 |

37.9% |

20 |

37.7% |

0.000* |

|

KSU |

39 |

18.9% |

14 |

13.0% |

28 |

41.2% |

48 |

25.3% |

4 |

7.5% |

||

|

PNU |

20 |

9.7% |

7 |

6.5% |

2 |

2.9% |

19 |

10.0% |

5 |

9.4% |

||

|

DAU |

15 |

7.3% |

6 |

5.6% |

7 |

10.3% |

10 |

5.3% |

5 |

9.4% |

||

|

Al Farabi |

31 |

15.0% |

25 |

23.1% |

3 |

4.4% |

26 |

13.7% |

17 |

32.1% |

||

|

KSUHS |

27 |

13.1% |

14 |

13.0% |

2 |

2.9% |

15 |

7.9% |

2 |

3.8% |

||

|

*Chi-square statistically significant, DAU: Dar Al Uloom University, KSU: King Saud University, KSUHS: King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, PNU: Princess Nourah University, REU: Riyadh Elm University |

||||||||||||

Discussion

This study aims to assess the awareness of ethics among dentists and dental students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. It has been determined that most dentists and dental students recognize that knowledge of the ethics related to their work is important. However, we found that 44.5% of those studied were not aware of the number of the main principles of ethics. Moreover, Kesavan et al. (1) reported that 39% of their study population reported that there were six main principles of ethics, which indicates that dentists and dental students do not have an adequate knowledge of wthics. On the other hand, knowledge of bioethics among dental students and dentists in Riyadh city was considered very important in their work (81.4%) which is consistent with previous investigations (8).

Lectures, seminars, and training were the most common sources from which our study participants obtained their knowledge. This is consistent with the previous investigation by Bebeau et al. (7) that revealed that most of their study participants had obtained their knowledge of bioethics from working experience. This proves that there is a greater focus by universities on the knowledge of ethics, as we also found that the level of education and university were significant predictors for most of the reported principles among our population. Previous studies have also reported that the levels of knowledge and practice were higher in specialists than recent graduates, which is probably due to the experience level and frequent exposure to ethically-related situations (13, 14).

Autonomy is an essential part of sound dental care practices that aim to elevate the quality of care and communication between the patient and the dentist (15, 16). It is widely known that the relationship between the dentist and the patient is the key factor when achieving successful outcomes in a dental practice, alleviating the need to stick to the dental ethics. Recent evidence shows that the best decision-making practices are those that depend on collaboration between the dentist and the patient to make decisions and obtain better clinical outcomes (17, 18). In the present study, 53.5% of our population reported that punctuality is not a principle of ethics. This is consistent with the findings of the previous study by Kesavan et al. (1). ?Moreover, 61.8% of the respondents did know the Hippocratic oath, which is in sharp contrast to a previous investigation that was conducted by Bebeau et al. (7). When asked about the principle of self-governance 53.8% answered with patient involvement, which is similar to a study by Tabei et al. (19). A previous investigation also reported that approximately two thirds of study participants reported that it is better to explain all the potential treatment alternatives rather than encouraging them to continue taking a certain drug. When patients believe in paternalism and autonomy, it establishes a certain degree of balance between the healthcare benefits and autonomy for the patient (20). The same study also reported that approximately 13% of the study participants were not obliged to make patients compely to certain groups of drugs and that patients were free to make their own decision (20). Porter et al. (21) also previously reported that almost all of their study participants reported that patients should be informed of potential treatment alternatives. Informed consent, confidentiality, and gaining assent from adolescents and children was also reported in a previous investigation (22). However, obtaining informed consent and maintaining the confidentiality of patients and their data has also been reported to be less common among many practicing dentists (14-16). This may be attributable to the habits and routine actions of the different countries studied as the reported rates of knowledge between dentists between these studies were also found to be different.

Furthermore, the respondents paired the principle of non-maleficence with a consultation referral (42.6%). However, this is not consistent with a study conducted by Tabei et al. (19) regarding the personal relationship with the patient. It should be noted that dentists are ethically responsible for explaining the hazards and effects of certain drugs and procedures and educating patients properly about their conditions. For instance, Nayak et al. (14) reported that approximately 97% of their study participants took responsibility for sharing adequate information about the duration and related costs of the procedures, which was also reported among other investigations in the literature (15, 23, 24). Moreover, previous investigations reported that most of their study participants agreed that it is not ethical for surgeons to share and discuss the appropriate treatment modality with others when dealing with patients with blood-borne infections (1, 25).

Furthermore, most of the respondents selected the principle of justice with patient selection while justifibile criticism was reported by Tabei et al. (19). Some principles may conflict with the principle of autonomy as it is widely known that some patients might be unwilling or unable to decide what is best for their dental care. Administration of inappropriate management modalities has been known to be a common problem for patients in this area. Accordingly, ethical problems may occur when patients are not able to make their own decisions. In the same context, a previous investigation reported that refusal of the suggested treatment approaches should not be differentiated from the patient’s preferences, and around one third also reported that surgeons can refuse to conduct a surgery regardless of the patient’s decision about their dental care (20). The previous investigation by Porter et al. (21) also indicated this by showing that most of the study participants agreed that surgeons and dentists can refuse the suggested management modality, while some of them reported that such behavior will make the dentist and the patient seem alike.

The main strength of this article is that it studies the associations of multiple exposures and outcomes. Data on all variables were only collected at a one-time point (26). These findings are limited to dental schools in Riyadh City. Therefore, it cannot be generalized for all dentists and dental students in Saudi Arabia. A significant article reveals learning resources that dentists and dental students in Riyadh city can use to learn more about ethics. Also, it helps them imply theoretical knowledge to their clinical practice, which highly improves patient service and safety. Further studies should be carried out to include other countries' experiences and adjust them to our religious and cultural beliefs, to meet patients' needs and rights. Conducting future studies to enhance the quality of education about ethics in dental schools is necessary (19).

Conclusion

Most of the participants were unaware of the five ethical components. Dentists and dental students should know more about those principles. The knowledge of a profession without being practiced is worthless, and knowledge without ethics can have a disastrous outcome.

Declaration:

Disclosure:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding:

None

Ethical consideration:

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for the study was obtained from the Riyadh Elm Univesity and the study proposal was registered in the research center under the registration number FUGRP/2018/215. Written informed Consent was obtained from participants in the form of an introductory statement at the begninng of the survey with an option to agree to it in order to complete the questionnaire.