Volume 2, Issue 11

November 2022

COVID-19 Infection in A Dedicated Regional ICU In Saudi Arabia: Patients` Characteristics and Outcome of Management

Bander AlMutairi, Amarachukwu C Etonyeaku, Afyaa Alriyaee , Abdulhadi AlHarbi, Dalal Alahmari, Abdullah Alazmi

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2022.21125

Keywords: COVID-19, ICU, patients, characteristics

Background: Coronavirus infection disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel viral respiratory tract infection that caused a global pandemic. It can be associated with many complications including acute respiratory failure which can lead to intensive care unit (ICU) admission. This study evaluates the characteristic of patients with COVID-19 admitted for ICU care, and determine factors associated with poor outcome of care.

Methodology: This is a retrospective review of patients admitted into the ICU of Buraidah Central Hospital on account of COVID-19 complications between March 2020 and October 2021. Records on patients` age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking habit, co-morbidities, ventilatory support type, the occurrence of pneumothorax, duration of ICU stay, and outcome of treatment of disease were extracted and analyzed for descriptive statistics, and the Chi-square test using SPSS version 28.

Results: A total of 1035 patients were admitted into the ICU due to COVID-19 infection. The mean age of the patients was 59.95±21.10 years (range = 5-104 years). There were more males (N=695, 67.1%) than females (340, 32.9%). The majority of the patients (545; 52.7%) were elderly, followed by middle-aged adults (360; 34.8%); and were either overweight or obese (N= 849, 82%). More patients (568, 54.9%) were admitted in the year 2020, compared to the year 2021(467; 45.1%). Similarly, mortality rates were higher in the year 2020 (252, 44.4%) than in 2021 (219; 46.9%). There was a significant association between hospital course and patients who had higher BMI, endotracheal intubation, pneumothorax, emphysema, and co-morbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus (p < .001). Also, there is a significant association between hospital course and the patient’s age, gender, and month of admission (p<.001).

Conclusion: COVID-19 was an indication for ICU admission. Most patients were middle-aged or elderly and were predominantly male. Most admissions occurred during summer, and there has been a steady decline in admission rates and mortality. The male gender, obesity, and other co-morbidities are associated with worse outcomes.

Introduction

The coronavirus infection disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused a pandemic that ravished the world from November 2019 till date. It is arguably the most remarkable global health challenge mankind has encountered thus far in this millennium. Although the number of new cases and deaths attributed to the disease has been on the decline since the first quarter of the year 2022, the pandemic came at a huge cost in terms of deaths and economic loss. In terms of the epidemiological burden of the disease, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that as of May 4, 2022, over 500 million confirmed cases and six million deaths have been recorded globally from the time the pandemic broke out (1). In terms of the economic burden of the disease, Alenzi et al in a national study done in Saudi Arabia between March 1, 2020, and January 30, 2021, estimated that the total direct cost of medical care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was about 193,394,103.1 SAR. This cost included the cost of ward and ICU admissions, laboratory tests, and treatment costs (2).

Coronaviruses are a wide family of viruses that cause illnesses ranging from the common cold to more serious diseases like middle east respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS is due to the COVID-19 virus, and the epicenter of the recent pandemic was believed to have originated from the Wuhan seafood and animal markets in China (3, 4). COVID-19 SARS is mostly spread by respiratory droplets and close contact with infected individuals (5). The major symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, cough, shortness of breath, and occasionally pneumonia (3). COVID-19 SARS shares some common features with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but there are many distinct pathophysiological mechanisms observed with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. These mechanisms include intravascular thrombosis induced by endothelial dysfunction, significant hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, and increased blood flow to a collapsed lung tissue; with bilateral lung involvement (6).

Mild cases of the infection may be asymptomatic and would not need in-hospital care. Severe cases would often require in-hospital care. Critically ill patients with respiratory or imminent respiratory failure would preferentially need intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and probable ventilatory support. Similarly, patients with pneumothorax would require the insertion of a closed thoracostomy tube drain connected to an underwater-seal apparatus.

Common complications associated with severe cases of COVID-19 include, but are not limited to, pneumonia, laryngitis, ARDS and respiratory failure, coagulopathy, acute kidney injury, and pleural disease. The presence of pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, or lymphadenopathy is thought not to be so common (7, 8).

In Saudi Arabia, the first COVID-19 case was reported on March 2, 2020, and the majority of verified cases, thereafter, were attributed to returning tourists and their close contacts (5). At the beginning of the pandemic, very little was known regarding the best approach to the management of the disease: due to its novel nature. The Saudi Arabian government through its Ministry of Health, developed policies and guidelines (9) to control the disease, and designated some health facilities as dedicated treatment centers for the care of COVID-19-related infections. Our hospital, Buraidah Central Hospital (BCH) was one such facility.

The principles of ICU care for patients with COVID-19 are premised on infection control and testing, supportive care (haemodynamic, respiratory, and organ support), and pharmacotherapy (antibiotics and steroids, when indicated, and COVID-19-specific treatment). The outcome of ICU care for the patients could be classified into complete recovery and discharge, some recovery with a residual disability, and death. During the early stages of the pandemic, the prevalence and mortality rates were high, but these have declined steadily (10-12). This decline has been attributed to a better knowledge of the disease, stringent enforcement of public health control measures, availability of medications and vaccines, and the development of herd immunity (12-15). Without prejudice to this decline, Auld et al reported seasonal variation in mortality rates due to COVID-19; and that this corresponds to periods of a surge in cases: during the fall and winter seasons (16).

From earlier works, some factors had been associated with poor outcomes among in-hospital COVID-19 patients. These factors included: advanced age and the presence of comorbidities like DM and cardiac diseases (13, 17, 18). Other documented associated factors for poor outcomes are gender, altered sensorium, and human immunodeficiency virus infection (19, 20). Li et al in a systemic review and meta-analysis found that male gender, old age, obesity, DM, and chronic kidney disease were associated with poor outcomes. However, they could not establish a similar association with chronic obstructive airway disease, cancer, and smoking (21).

This report evaluated the characteristics and management outcomes of patients admitted into our ICU as a result of complications of covid 19 infection; we also evaluated probable factors associated with mortality among them.

Methodology

Study settings and design

This was a retrospective, chart study involving all COVID-19 patients admitted into the ICU of the BCH, Al Qassim, Saudi Arabia. The hospital is a 460-bedded tertiary hospital that serves as a trauma center, and during the pandemic was designated the regional intensive care center for confirmed COVID-19 patients. The ICU services of the hospital were split into two sections: one for COVID-19-positive patients (50 beds), and the other for those without the disease who require ICU care for other conditions.

Study population and data collection

All patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection who were admitted into the specialized ICU of the BCH between March 1, 2020, and October 31, 2021 (20 months duration) were included in the study. Patients who had COVID-19 but did not require ICU care were excluded. Similarly, patients admitted into the ICU for other conditions not related to COVID-19 were also excluded.

The admissions register of the ICU dedicated to the care of COVID-19 cases was reviewed to cover the period of study and the medical records. The patients` number obtained from the register, was used to access the details of patients` medical records within the hospital`s electronic medical records systems hosted on VIDA® by Clouds Solution International. The medical records were analyzed for patients` age, gender nationality, month and year of admission to the ICU, smoking habit, co-morbidities, ventilatory support type, presence of pneumothorax, and outcome of treatment of disease (hospital course). This study categorized ventilatory support into patients who had endotracheal tube insertion with mechanical ventilation, and those who did not. The latter group included those patients who had oxygen via nasal prongs or nasal catheters and those who had assisted ventilation using Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) device.

For this study, we similarly categorized the outcome of treatment (the hospital course) into two broad groups: those who survived and were discharged from the ICU, and those who died while on ICU admission.

Data storage and analysis

The data generated was entered into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft) on a personal computer and can be available upon request when necessary. The Excel database was subsequently exported to, and analyzed using, the SPSS® version 28 (© IBM incorporated). Analyses were for simple proportions and percentages, and measures of central tendencies. Also, parametric tests were used to compare means or categorical variables between groups. The parametric tests were set at a 95% confidence interval. Results are presented in prose, tables, and charts.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the General Directorate of Health Affairs Al Qassim Region (approval number: 1443-1143496). The study was done in full compliance with the Helsinki declaration and its modification by the World Medical Association.

Results

A total of 1035 patients were admitted to the ICU of the hospital on account of COVID-19-related conditions. The unit received 568 patients in 2020 (March to December) and 467 in 2021 (January to October) consisting of 54.9% and 45.1% of all COVID-19 admission respectively for the study period. The monthly admission rates also varied showing relatively higher rates for the months of July, August, and October for each year (Table 1). Furthermore, the study revealed that the age of the patients ranged from 5 years to 104 years with a median age of 60 years. There were more males (N=695, 67.1%) than females (340, 32.9%), giving a male: female ratio of 2:1. The majority of the patients (545; 52.7%) were elderly, followed by middle-aged adults (360; 34.8%); and were either overweight or obese (N= 849, 82%). However, very few patients (1.4%) had a smoking history. Furthermore, the results indicated that the observed rate of co-morbidities among the patients was 71.7% (n=742), with the majority of the patients (63%, n=652) having multiple co-morbidities. The disposition of these co-morbidities and patients` BMI are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for Sociodemographic & Clinical Characteristics |

|||

|

Variable |

Category |

f |

% |

|

Age |

Young Adults |

130 |

12.6 |

|

Middle-aged Adults |

360 |

34.8 |

|

|

Old Adults |

545 |

52.7 |

|

|

Gender |

Female |

340 |

32.9 |

|

Male |

695 |

67.1 |

|

|

Hospital Course |

Discharged |

564 |

54.5 |

|

Expired |

471 |

45.5 |

|

|

Months of Admission |

January |

9 |

.9 |

|

October |

54 |

5.2 |

|

|

November |

12 |

1.2 |

|

|

December |

31 |

3.0 |

|

|

February |

8 |

.8 |

|

|

March |

30 |

2.9 |

|

|

April |

80 |

7.7 |

|

|

May |

50 |

4.8 |

|

|

June |

183 |

17.7 |

|

|

July |

270 |

26.1 |

|

|

August |

218 |

21.1 |

|

|

September |

90 |

8.7 |

|

|

Year of Admission |

2020 |

568 |

54.9 |

|

2021 |

467 |

45.1 |

|

|

BMI |

Underweight |

11 |

1.1 |

|

Normal Weight |

175 |

16.9 |

|

|

Pre-Obesity |

401 |

38.7 |

|

|

Obesity Class-I |

201 |

19.4 |

|

|

Obesity Class-II |

84 |

8.1 |

|

|

Obesity Class-III |

26 |

2.5 |

|

|

Intubated |

No |

587 |

56.7 |

|

Yes |

448 |

43.3 |

|

|

Pneumothorax |

No |

989 |

95.6 |

|

Yes |

46 |

4.4 |

|

|

Emphysema |

No |

1001 |

96.7 |

|

Yes |

34 |

3.3 |

|

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

No |

544 |

52.6 |

|

Yes |

491 |

47.4 |

|

|

Hypertension |

No |

585 |

56.5 |

|

Yes |

450 |

43.5 |

|

|

Cardiovascular diseases |

No |

926 |

89.5 |

|

Yes |

109 |

10.5 |

|

|

Central Line |

No |

870 |

84.1 |

|

Yes |

165 |

15.9 |

|

|

Smoking History |

No |

1021 |

98.6 |

|

Yes |

14 |

1.4 |

|

* f: frequency

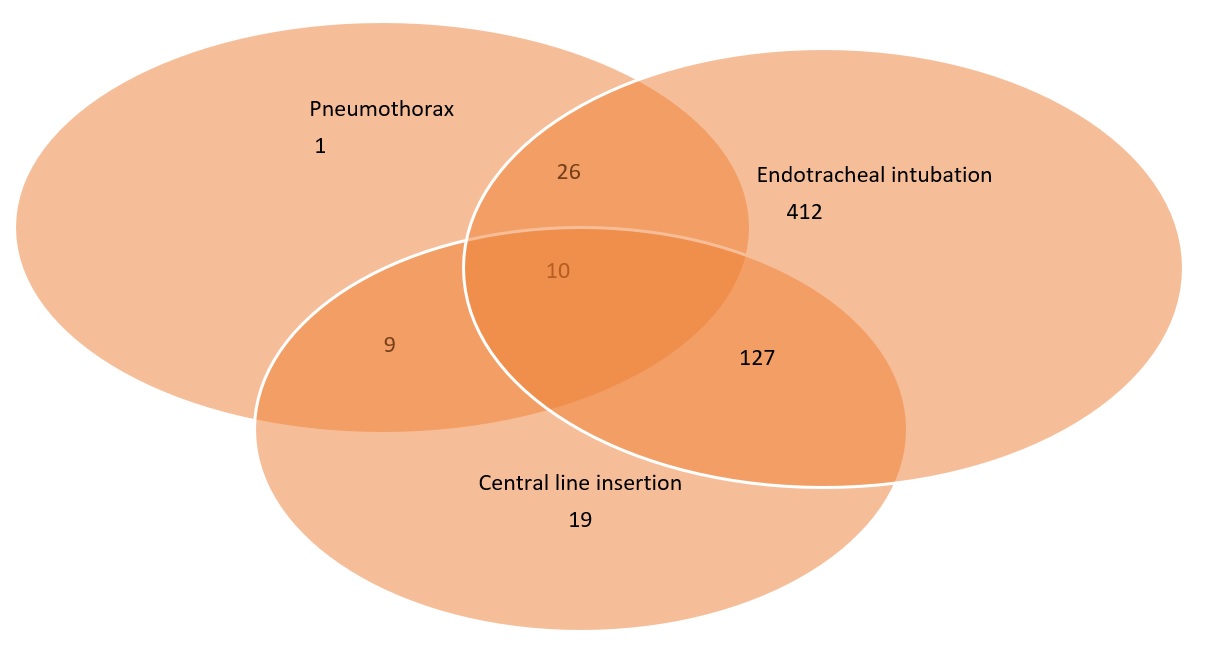

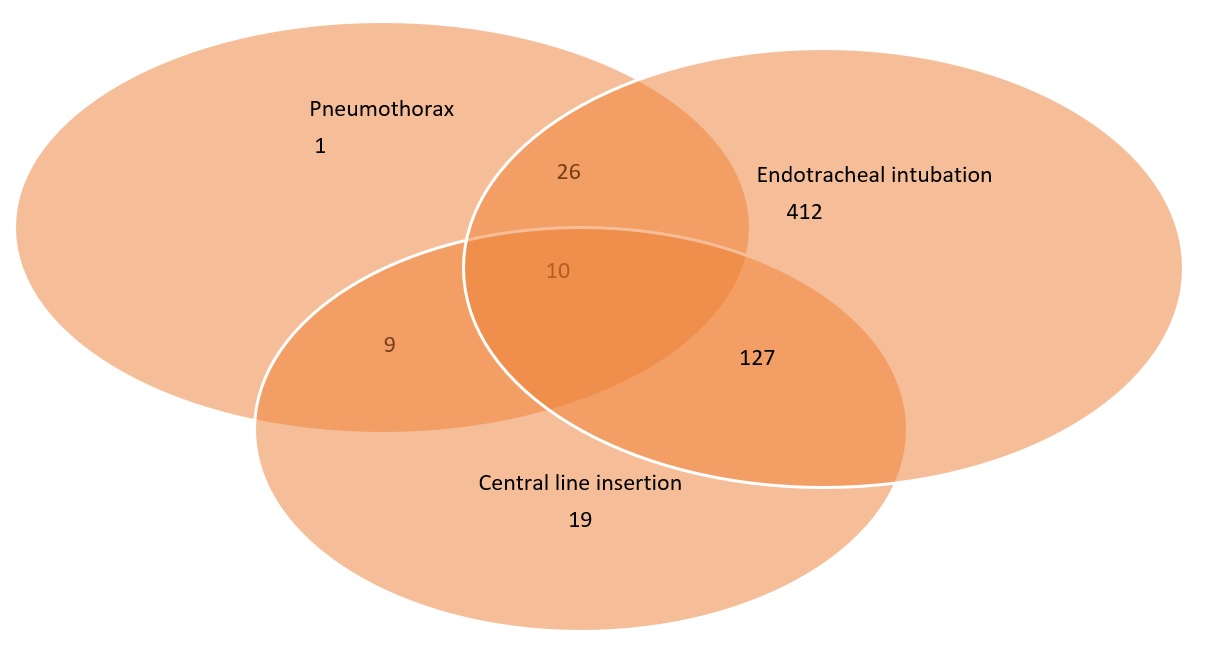

Moreover, 448 (43.3%) patients had endotracheal intubation for ventilatory support, while 165 (15.9%) had a central venous catheter insertion for fluid, medications, and nutritional management. Furthermore, the study showed that 46 (4.4%) patients had pneumothorax, while 34 patients (3.3%) had subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 1). All, 46 patients with pneumothorax (including those with associated subcutaneous emphysema) had closed-tube thoracostomy drain using an underwater seal.

Figure 1: Venn diagram establishing a relationship between pneumothorax, endotracheal intubation, and institution of central venous line.

The Chi-square test for factors associated with the hospital course (outcome of care) of patients indicated a significant association between hospital course and patients who had endotracheal intubation, pneumothorax, emphysema, and co-morbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus (p <.001). This implies that those patients who were intubated, had complications such as pneumothorax and emphysema, or were suffering from co-morbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus were more likely to die while on admission in the ICU (p<.001) than those who were not intubated, or had afore-mentioned co-morbidities or complications. However, the Chi-square test did not reveal any statistically significant association between the hospital course of patients and the history of cardiovascular disease, smoking, asthma, BMI, or COPD (p >.05). Table 2 shows details of these. In contrast, we found a strong association, on the Chi-square test, between hospital course and the age and gender of patients, and the month of admission to the ICU (p<.001).

|

Table 2: Showing Frequencies and Chi-square Results for Hospital Course and Clinical Factors (N=1035) |

|||||

|

Variable |

Category |

Observation |

Hospital Course |

p-value |

|

|

Discharged |

Expired |

||||

|

Intubated |

No |

Count |

500 |

87 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

319.9 |

267.1 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

64 |

384 |

||

|

Expected Count |

244.1 |

203.9 |

|||

|

Pneumothorax |

No |

Count |

553 |

436 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

538.9 |

450.1 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

11 |

35 |

||

|

Expected Count |

25.1 |

20.9 |

|||

|

Emphysema |

No |

Count |

558 |

443 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

545.5 |

455.5 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

6 |

28 |

||

|

Expected Count |

18.5 |

15.5 |

|||

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

No |

Count |

334 |

210 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

296.4 |

247.6 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

230 |

261 |

||

|

Expected Count |

267.6 |

223.4 |

|||

|

Hypertension |

No |

Count |

352 |

233 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

318.8 |

266.2 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

212 |

238 |

||

|

Expected Count |

245.2 |

204.8 |

|||

|

Cardiac diseases |

No |

Count |

512 |

414 |

.133 |

|

Expected Count |

504.6 |

421.4 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

52 |

57 |

||

|

Expected Count |

59.4 |

49.6 |

|||

|

Central line |

No |

Count |

525 |

345 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

474.1 |

395.9 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

39 |

126 |

||

|

Expected Count |

89.9 |

75.1 |

|||

|

Smoking |

No |

Count |

557 |

464 |

.734 |

|

Expected Count |

556.4 |

464.6 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

7 |

7 |

||

|

Expected Count |

7.6 |

6.4 |

|||

|

Asthma |

No |

Count |

535 |

441 |

.396 |

|

Expected Count |

531.8 |

444.2 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

29 |

30 |

||

|

Expected Count |

32.2 |

26.8 |

|||

|

COPD |

No |

Count |

560 |

466 |

.543 |

|

Expected Count |

559.1 |

466.9 |

|||

|

Yes |

Count |

4 |

5 |

||

|

Expected Count |

4.9 |

4.1 |

|||

|

BMI |

Underweight |

Count |

8 |

3 |

.184 |

|

Expected Count |

6.5 |

4.5 |

|||

|

Normal Weight |

Count |

102 |

73 |

||

|

Expected Count |

103.9 |

71.1 |

|||

|

Pre-Obesity |

Count |

245 |

156 |

||

|

Expected Count |

238.0 |

163.0 |

|||

|

Obesity Class-I |

Count |

114 |

87 |

||

|

Expected Count |

119.3 |

81.7 |

|||

|

Obesity Class-II |

Count |

54 |

30 |

||

|

Expected Count |

49.9 |

34.1 |

|||

|

Obesity Class-III |

Count |

10 |

16 |

||

|

Expected Count |

15.4 |

10.6 |

|||

* p-value < 0.05 is statistically significant

Table 3: The overall mortality rate from the study was 45.5% (N=471), while the remainder of 564 patients (54. 5%) made a significant recovery and were discharged from the ICU. We, however, observed that the number of deaths per total admissions (case fatality rate, CFR) was lower in 2020 (44.4%; 252/568) when compared with figures from 2021(46.9%, 219/476), but this was found not to be statistically significant (p > 0.05). Also, the CFR among female patients (50.3%) was relatively higher than that for males (43.2%). This pattern of female dominance was also found to exist for each of the two years: 2020 (47.9% vs 43.1%) and 2021 (52.0% vs 43.2%). Notably, those patients who were admitted to the ICU in the months of July, August, and October were from the old adult female group and exhibited a higher frequency of mortality and lower frequency of discharge as compared to those who were admitted in the other months of the year and were from the middle-aged and young adult male group (p<.001).

|

Table 3: Showing the Frequencies and Chi-square Results for Hospital Course and Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Population (N=1035) |

|||||

|

Variable |

Category |

Observation |

Hospital Course |

p-value |

|

|

Discharged |

Deceased |

||||

|

Months |

January |

Count |

5 |

4 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

4.9 |

4.1 |

|||

|

October |

Count |

22 |

32 |

||

|

Expected Count |

29.4 |

24.6 |

|||

|

November |

Count |

8 |

4 |

||

|

Expected Count |

6.5 |

5.5 |

|||

|

December |

Count |

19 |

12 |

||

|

Expected Count |

16.9 |

14.1 |

|||

|

February |

Count |

4 |

4 |

||

|

Expected Count |

4.4 |

3.6 |

|||

|

March |

Count |

18 |

12 |

||

|

Expected Count |

16.3 |

13.7 |

|||

|

April |

Count |

53 |

27 |

||

|

Expected Count |

43.6 |

36.4 |

|||

|

May |

Count |

35 |

15 |

||

|

Expected Count |

27.2 |

22.8 |

|||

|

June |

Count |

109 |

74 |

||

|

Expected Count |

99.7 |

83.3 |

|||

|

July |

Count |

135 |

135 |

||

|

Expected Count |

147.1 |

122.9 |

|||

|

August |

Count |

95 |

123 |

||

|

Expected Count |

118.8 |

99.2 |

|||

|

September |

Count |

61 |

29 |

||

|

Expected Count |

49.0 |

41.0 |

|||

|

Year of Admission |

2020 |

Count |

316 |

252 |

.416 |

|

Expected Count |

309.5 |

258.5 |

|||

|

2021 |

Count |

248 |

219 |

||

|

Expected Count |

254.5 |

212.5 |

|||

|

Age Groups |

Young Adults |

Count |

102 |

28 |

<.001* |

|

Expected Count |

70.8 |

59.2 |

|||

|

Middle-aged Adults |

Count |

236 |

124 |

||

|

Expected Count |

196.2 |

163.8 |

|||

|

Old Adults |

Count |

226 |

319 |

||

|

Expected Count |

297.0 |

248.0 |

|||

|

Gender |

Female |

Count |

169 |

171 |

.031* |

|

Expected Count |

185.3 |

154.7 |

|||

|

Male |

Count |

395 |

300 |

||

|

Expected Count |

378.7 |

316.3 |

|||

* p-value < 0.05 is statistically significant

Discussion

Qassim region, in the central part of Saudi Arabia, has an estimated population of 1,275,782 (22). An earlier study done in Saudi Arabia reported that the Qassim region had a relatively lower prevalence of COVID-19, CFR, and incidence density per 100 person days (23). Age distribution varies between countries: some authors report that it is more common in elderly patients while others suggest a changing pattern in the age distribution of the disease (24, 25). In this study, we found that elderly patients were most commonly afflicted by COVID-19. In contrast, the disease appears not so common in children: who also fared better if at all infected (26). This was also in consonance with our findings. There was a paucity of data from the paediatrics age group which may be due to the services of a specialized hospital with fully functional paediatrics intensive care within the same town as our facility. Relatively more cases were seen in the year 2020 as this was about the time the pandemic was at its peak. Also at this time, herd immunity was low, guidelines for COVID-19 control and treatment were just in formulation stages, and vaccines were undergoing trials. With the advent of stringent control measures and vaccination, the incidence of the disease, in-patient and ICU admissions, and mortality rates dropped as noted in this study. The male preponderance in this study (M: F= 2:1) corroborates earlier works by Abohamr et al. (5). It has been suggested that this may be due to males having a higher expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2, differences in immunity based on sex hormones and chromosome X, risky lifestyles, and poor attitudes to control measures (27). This may also explain the relatively higher mortality rates seen in males in this study.

COVID-19, like most viral flu, has been associated with periods of lower environmental temperatures (28-30). We cannot explain the high admission rates in July and August observed in our study; as these times were outside the winter season, and environmental temperatures are relatively higher compared to other months of the year. The relatively higher proportion of the elderly and late middle-aged groups may be a result of declining immunity and associated co-morbidities common in such age group (31, 32).

Common co-morbidities encountered in this study were hypertension, DM, and obesity, and all these were statistically associated with poor outcomes of care (p< 0.005). Parohan et al. (33) had earlier reported that age (p<0.001), gender (p=0.021), hypertension (p=0.003), cardiovascular diseases (p=0.001) chronic obstructive airway disease (p<0.001), and cancer (p<0.001) were common co-morbidities that were associated with poor outcome. Although Leoni et al(34) observed that obesity (12.8%), hypertension (46.7%), and DM (15.3%) were common co-morbidities, only age (p=0.0002), obesity (0.03), and length of ICU stay (p<0.0001) were statistically significant predictors of mortality. However, Auld et al (35) reported significant risk for patients who are not morbidly obese (p=0.025), patients with chronic kidney disease (p=0.022), or those who had mechanical ventilation (p<0.001). Unlike our findings, Umeh et al. (36) in their review noted that for patients admitted into the ICU, BMI (p=0.947) and presence of co-morbidities (p>0.05) did not predict mortality.

The major indication for ICU admission was respiratory, or incipient respiratory failure and airway control; and this is in tandem with established guidelines by regulatory authorities (9, 37). The modalities of respiratory support included nasal canular, facemask, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices, endotracheal tubes with mechanical ventilation, and in some cases prone positioning.

Pneumothorax has been reported as a complication of COVID-19 pneumonia (38); It could also arise as an iatrogenic complication of such procedures as central venous cannulation (pleural puncture) and mechanical ventilation (barotrauma). Irrespective of the aetiology of the pneumothorax, it is generally associated with poorer prognosis (38, 39) and this was what we found in this study. Martinelli et al however do not agree that pneumothorax on its own would cause a poor management outcome (40). Smoking is implicated in the etiology of COPD, and it has been established that a history of smoking is strongly associated with the likelihood of patients requiring mechanical ventilation among covid 19 patients (41) with attendant poorer prognosis (42, 43).

This study’s limitations were chiefly due to the challenges of most retrospective studies. There was poor record keeping characterized by the absence of some information, or when recorded, the information given was incomplete. Also, we could not access details of the clinical course, including ventilatory settings which may have impacted the outcome. Also, post-discharge events and follow-ups were very scanty, and thus, were not pursued.

Conclusion

This study showed that all age groups and gender can develop severe COVID-19 requiring ICU admission. Most of our patients were in the middle-aged to elderly category and were predominantly males. The admission rate was higher during the early period of the pandemic and varied between months of the year. Common co-morbidities were hypertension, DM, and obesity. Mortality was more among males, but the CFR was more among females. The older the patient`s age, male gender, obesity, DM, mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube, and complications like pneumothorax were associated with mortality. On the other hand, smoking, asthma, and COPD are not associated with mortality. There is a need for further studies to fully explore the role of these factors in the treatment outcomes of critically ill patients admitted to the ICU for COVID-19 complications, as this will help in the timely management of COVID-19 patients in the future.

Disclosure

Statement:

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding this work.

Funding:

None.

Ethical Consideration:

This work adhered to Helsinki`s declaration and obtained ethical clearance (No: 1443-1143496 of 23/06/1443) from the Ministry of Health, General Directorate of Health Affairs Al Qassem region.

Data availability:

All complete data sets obtained from this study were used in preparing this manuscript. The raw data is held in the custody of the authors within their personal computers or electronic storage system.

Author Contribution:

MB, EAC, AA, AA, DA, AA contributed to the conceptualization, MB, EAC, AA, AA, DA, AA in the study design, AA, AA, DA, AA in data collection, EAC, BM in analysis, EAC in manuscript drafting and MB, EAC, AA, AA, DA, AA in manuscript review and approval.