Volume 6, Issue 1

January 2026

The Efficacy of High-Frequency Oscillatory Ventilation in Pediatric and Adult Patients

Hamed Saeed Alghamdi, Sameerah Waheed Aqdi, Seham Qassim Alhaffaf, Mashael Nasser Matabi, Ali Qasem Sufyani, Alwaleed Ali Yahya, Salem Saleh Alyami

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2026.60122

Keywords: High-frequency oscillatory ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure, ventilator-induced lung injury

High-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) is a promising rescue therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and acute lung injury, especially when conventional mechanical ventilation has failed. HFOV is a unique ventilatory mode in which it delivers low tidal volumes of breath in very high frequencies utilizing high mean airway pressures. This ventilation mode keeps the collapsed alveoli open and prevents the cyclic derecruitment of the lung while minimizing alveolar overdistension. Hence, HFOV is considered a suitable lung-protective ventilation strategy for people at risk of development of ventilator-induced lung injury. However, there are several controversies surrounding the use of HFOV, including its use as an early treatment for ARDS, its effectiveness in reducing mortality, and its efficacy in oxygenation improvement for high-risk clinical subpopulations, in addition to the associated adverse effects. Therefore, optimal and safe application of HFOV as rescue therapy requires careful HFOV titration based on each individual patient, along with monitoring of important physiological parameters. In this narrative review we aim to explore current evidence regarding the efficacy of HFOV in pediatric and adult patients, focusing on the physiological mechanism of HFOV and its efficacy in oxygenation improvement for management of respiratory failure and ARDS, in addition to clinical challenges and current limitations to HFOV. Future studies should target subpopulations of patients who may benefit from HFOV, along with implementation of consistent protocols for HFOV.

Introduction

Respiratory failure is one of the main causes for intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Most of the patients, especially children, who require mechanical ventilation can be supported with conventional mechanical ventilation (CMV); however, certain cases with refractory hypoxemia or hypercapnia may need more advanced ventilatory modes (1). Moreover, CMV is associated with pulmonary structure damage and ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). There are four main pathogenesis mechanisms that are responsible for VILI development, which are volutrauma, caused by overstretching the alveoli; barotrauma, caused by trans-alveolar over-pressurization; atelectrauma, caused by repeated opening and collapse of the alveoli resulting in shear stress; and biotrauma, the resulting inflammatory response to tissue damage, which leads to lung and multi-organ failure (2).

High-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) is a common rescue therapy for infants and children with respiratory failure. It is considered an effective ventilation mode in several diseases that affect a child in the postnatal period, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), meconium aspiration syndrome, postnatal pulmonary bleeding, as well as idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (3). For adult patients, HFOV is considered a suitable rescue strategy for management of refractory hypoxemia in ARDS. It is also recommended for ARDS patients with VILI or those who are more likely to develop VILI, especially when CMV has failed (4, 5).

The difference between HFOV and CMV is that HFOV delivers very small breaths at very high rates (180 to 900 breaths per minute), which helps with the opening of collapsed alveoli through providing constant positive pressure in the airway. This mode of action makes HFOV an ideal lung-protective ventilation mode for ARDS management, because the application of high mean airway pressures (mPaw) prevents the cyclical derecruitment of lung, while the small tidal volumes (VT) prevent overdistension of alveoli (6). Therefore, HFOV allows for achieving the beneficial effects on oxygenation and ventilation, along with preventing the characteristic “inflate–deflate” cycle of CMV that contributes to VILI (4).

However, the use of HFOV in an ICU setting is considered challenging due to the need for careful optimization of several parameters for optimal and safe HFOV application. These parameters include mean airway pressure (mPaw), frequency (Hz), inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio, and tidal volume (VT), and they should be adapted to the individual patient according to pathophysiology, lung volume state, as well as patient’s age and size (7). This narrative review aims to summarize current evidence regarding the efficacy of HFOV in pediatric and adult patients, with a focus on the physiological mechanism of HFOV and its efficacy in oxygenation improvement for the management of pulmonary failure and ARDS, in addition to clinical challenges and current limitations to HFOV.

Methodology

This narrative review is based on a thorough literature search conducted on 9 December 2025 in PubMed, Cochrane, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. Using medical subject headings (MeSH) and relevant keywords, the search aimed to identify studies investigating the efficacy of HFOV in pediatric and adult patients. The review focused on articles that examine the physiological mechanism of HFOV and its efficacy in oxygenation improvement in pediatric and adult patients with respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome, in addition to clinical challenges and limitations to HFOV. To ensure a broad and comprehensive investigation of the available literature, no restrictions were applied regarding publication date, language, or type of publication.

Discussion

Physiological mechanism of HFOV

The main characteristic that distinguishes HFOV from CMV is that both inspiration and expiration are active. During HFOV, oxygenation and ventilation are considered independent, where oxygenation (PaO2) is controlled by fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) and mean airway pressure (mPaw) and ventilation is controlled by amplitude and frequency (1). For optimizing oxygenation, adjustment of mean airway pressure is critical. Compared to CMV, HFOV utilizes higher mPaw, which increases the alveolar surface area for gas exchange. It is used for recruitment of atelectatic alveoli while preventing derecruitment. Careful lung recruitment is critical to avoid alveolar overdistension (4, 6). In the initial application of HFOV, mPaw should be adjusted 3–5 cm H2O higher than the mPaw that was previously applied during CMV (8).

To optimize ventilation, amplitude and frequency (Hz) are adjusted, along with the chest wiggle. Amplitude is adjusted through the power control to manipulate the delivered tidal volume. It should be increased if the patient is under-ventilated and the amount of CO2 in blood (PaCO2) level is high to blow off more PaCO2. On the other hand, if the patient is over-ventilated and the PaCO2 level is low, then amplitude should be decreased so that less PaCO2 is eliminated (4). To adjust the amplitude in HFOV, arterial blood gas should be obtained and PaCO2 levels determined. Amplitude is adjusted to obtain a visible chest wiggle (9). Chest wiggle is used to assess the suitability of the power setting, with increased chest wiggle as an indicator to increased amplitude. Chest wiggle should be reassessed following positional changes. Diminished or absent chest wiggle indicates decreased pulmonary compliance, endotracheal tube disconnection or obstruction, or severe bronchospasm, while unilateral chest wiggle indicates endotracheal tube displacement (right mainstem) or pneumothorax (10).

As for adjusting the frequency (Hz) for optimal ventilation and CO2 removal, it depends on lung size, extent of lung injury, lung function, state of disease, along with the patient’s size. Generally, children are managed with higher frequencies compared to adults, with some variations in management (11). A frequency of 10–12 Hz may be used for management of an infant on HFOV, while a frequency of 5–8 Hz may be required for a larger child or an adult. It is worth noting that this also depends on the HFOV management strategy, degree of lung injury, and lung mechanics (12).

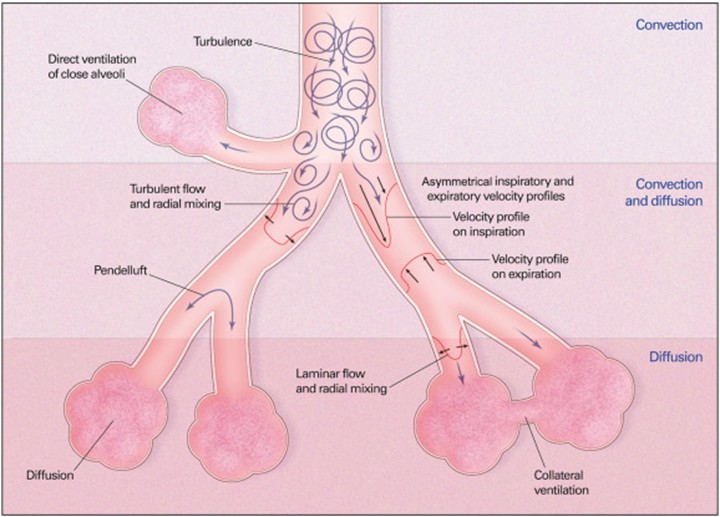

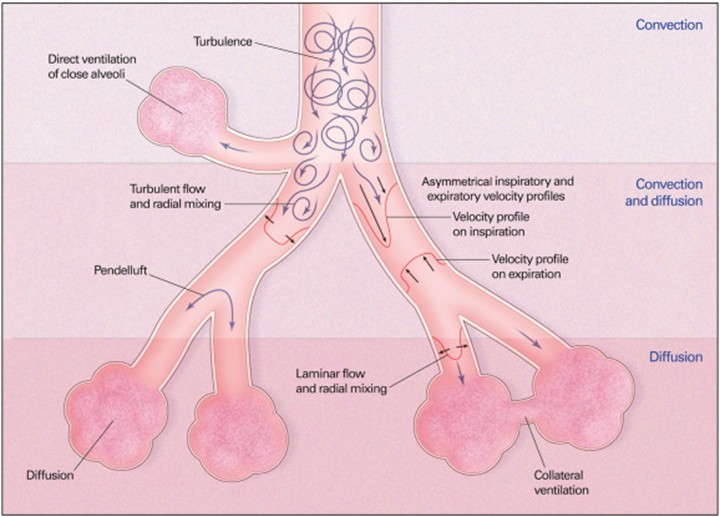

The main mechanisms of gas exchange that occur during HFOV in convection, convection–diffusion, and diffusion regions include: 1) turbulence in large airways producing improved mixing, 2) bulk convection (direct ventilation of close alveoli), 3) asymmetric inspiratory and expiratory velocity profiles (gas mixing due to velocity profiles that are axially asymmetric leading to streaming of fresh gas toward alveoli along the inner wall of the airway as well as streaming of alveolar gas away from the alveoli along the outer wall), 4) pendelluft (asynchronous flow among alveoli due to asymmetries in airflow impedance), 5) cardiogenic mixing (rhythmic, pulsatile nature of the heart conferring a mixing of gases), 6) Taylor dispersion (laminar flow with lateral transport by diffusion), 7) collateral ventilation between neighboring alveoli through non-airway connections, and 8) molecular diffusion. All these mechanisms, except molecular diffusion, depend on convective fluid motion (12, 13). The physiology of gas exchange is considered similar between children and adults, however, there are some distinctions. Infants and children have shorter time constants, which leads to different HFOV setting requirements (11). The main mechanisms for gas exchange in HFOV are illustrated in Figure 1.

Efficacy of HFOV in the pediatric population

The first randomized controlled trial (RCT) to investigate the efficacy of HFOV in children was conducted by Arnold, Hanson (14), and it included 70 children with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure. Results revealed significant improvement in oxygenation in the HFOV group compared with the CMV group. Moreover, HFOV reduced the need for supplemental oxygen in 30 days and was associated with a lower frequency of barotrauma. However, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality between HFOV and CMV groups (14). A more recent RCT investigated the efficacy of HFOV in 18 children with severe ARDS revealed that HFOV when combined with lung volume recruitment maneuver showed improved oxygenation and better clinical outcomes compared with CMV, and there was no significant effect on hemodynamic parameters (15).

Another RCT conducted by El-Nawawy, Moustafa (16) examined the outcomes of HFOV in 200 children with severe ARDS. HFOV showed significant improvement in oxygenation in comparison with CMV, however, there were no differences in 30-day mortality, length of stay or ventilation days between HFOV and CMV groups. Furthermore, multi-organ dysfunction syndrome was found to be the most common cause of death in this study and not refractory hypoxemia, which is the primary concern in pediatric ARDS. This implies that mortality in pediatric ARDS is multi-factorial and not only affected by fast oxygenation improvement.

Figure 1: Mechanisms of gas exchange during HFOV (5).

A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs that investigated the efficacy of HFOV in comparison to CMV in pediatric patients with ARDS was conducted by Junqueira, Nadal (17). Findings revealed insufficient evidence to determine the superiority of HFOV over CMV. Moreover, there were no significant differences in mortality rate, ventilation time, or barotrauma risk between HFOV and CMV groups. Despite the improvement in oxygenation exhibited in several trials conducted on pediatric patients managed with HFOV, the data are very limited due to the low-quality clinical trials and do not support the use of HFOV for children with ARDS. However, HFOV remains widely utilized in pediatric ICUs (12). This highlights the importance of increasing the quality of clinical trials that investigate the efficacy of HFOV in pediatric patients, and implementation of standardized protocols in these trials to ensure their success, along with monitoring important physiological parameters.

Efficacy of HFOV in the adult population

One of the early clinical trials that investigated the efficacy of HFOV in adult patients with ARDS has been conducted by Derdak, Mehta (18). The study included 148 ARDS adult patients and results revealed significant improvement in oxygenation in HFOV group. However, there was no effect on 30-day mortality reduction. Moreover, there were no significant differences in hemodynamic parameters, barotrauma frequency, oxygenation failure, or ventilation failure between HFOV and CMV groups, which proposed HFOV as a safe and effective ventilation mode for ARDS management in adults.

Moreover, HFOV was initially used as a rescue therapy for refractory hypoxemia in adults with respiratory failure. A large retrospective study conducted by Mehta, Granton (19) investigated the use of HFOV for refractory hypoxemia in 156 adult patients. Results revealed significant improvement in oxygenation, as well as PaO2/FiO2 ratio. The reported adverse effects included increase in central venous pressure, reduction in cardiac output, and increase in pulmonary artery occlusion pressure. Furthermore, the 30-day mortality rate in the study was 61.7%, which is higher than the 30-day mortality rate reported by Derdak, Mehta (18).

The OSCAR (Oscillation in ARDS) trial was a multicenter RCT that investigated the use of HFOV in 795 adult patients with ARDS from 2007 to 2012. Results of OSCAR trial showed improvement in oxygenation in the HFOV group in comparison with the CMV group, however, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality rate between the HFOV and CMV groups (20). Contrastingly, the OSCILLATE (Oscillation for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Treated Early) trial, which was another multicenter RCT that examined early HFOV administration for moderate-to-severe ARDS in adult patients, was prematurely terminated due to observed higher in-hospital mortality rate among the HFOV group (47%) compared with the control group (35%) who received CMV. Moreover, a non-significant increase in the rate of new-onset barotrauma was observed in the HFOV group (21).

Following the publication of OSCAR and OSCILLATE trials, the use of HFOV for adult patients has significantly declined as shown in the meta-analysis study of ARDS management patterns conducted by Tatham, Ferguson (22). Moreover, a Cochrane review of 10 RCTs that investigated the use of HFOV for management of moderate-to-severe ARDS in adults showed that HFOV does not reduce hospital and 30-day mortality, and the use of HFOV as a first-line ventilation mode is not recommended for patients who require mechanical ventilation for ARDS (23). This underscores the importance of considering HFOV as rescue therapy instead of early intervention, and to be used for only patients who may benefit from it, along with careful titration of HFOV and consistent monitoring of important physiological parameters.

Clinical challenges and limitations

Barotrauma is one of the pathogenesis mechanisms that contribute to VILI development. It refers to a group of symptoms that result from high mPaw applied during HFOV, which include pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, and subcutaneous emphysema (24). There are contrasting results regarding whether there is an association between HFOV and risk of barotrauma development. A meta-analysis study conducted by Meade, Young (25) revealed that HFOV increased the risk of barotrauma in adults with ARDS compared with CMV. Contrastingly, a meta-analysis study by Sud, Sud (26) found no significant effect of HFOV on barotrauma risk in adults and children with ARDS in comparison with CMV. Moreover, another meta-analysis study by Gu, Wu (24) revealed that HFOV did not have a significant effect on barotrauma risk in adult patients with ARDS. These findings support the use of HFOV as rescue therapy for ARDS patients; however, clinicians should avoid the use of high mPaw and only apply it with great care and caution (5).

Furthermore, HFOV is less effective for diseases that are characterized by increased airway resistance, as it can lead to gas trapping and hyperinflation and worsening of existing conditions. Such conditions include pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, as well as pulmonary interstitial emphysema (18, 27, 28). Cardiovascular complications are frequently reported in HFOV. These complications include increase in central venous pressure and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure, along with decrease in cardiac output (18, 19). The increase in central venous pressure as well as pulmonary artery occlusion pressure are likely the results of increased mPaw during HFOV (6). While decreased cardiac output results from increased lung volume due to decrease in venous return (29). Other cardiovascular complications include intraventricular hemorrhage, specifically in neonates, and increased intrathoracic pressures (28).

There are other complications to HFOV that are ventilator-associated and directly related to intubation. A retrospective study, which examined the clinical characteristics of children treated with HFOV, reported mucus plugging as one of the frequent complications (30). The desiccation of secretions during HFOV potentially contributes to mucus plugging and endotracheal tube obstruction (18). Therefore, adequate humidification is recommended to lower the frequency of this adverse effect (6). Moreover, ventilator-associated pneumonia is one of the common complications of HFOV (31). This is due to the invasive intubation that compromises the patient’s natural immune defense mechanisms, which increases the risk for lower respiratory tract infection and sepsis development (32).

Furthermore, HFOV is not suitable for certain subpopulations. A Cochrane review by Ethawi, Abou Mehrem (33) examined the risks and benefits of HFOV for preterm infants with pulmonary dysfunction. A long-term lung injury known as chronic lung disease (CLD) occurs frequently in preterm infants who require ventilation. Development of CLD is also affected by the ventilation mode applied, with CMV contributing to CLD occurrence in preterm infants. The review reported no clear evidence of superiority of HFOV over CMV for this subpopulation. This highlights the need for further research targeted at high-risk subpopulations, taking into consideration the concerns about increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage and CLD.

Future directions

Future studies should target subpopulations of patients who may benefit from oxygenation improvement during HFOV, such as those with severe hypoxemia at baseline or those who fail CMV due to refractory hypoxemia, or who may require higher mean airway pressures to facilitate alveolar recruitment, such as those with morbid obesity. Moreover, it is critical to implement consistent protocols for optimal application of HFOV to improve the success of future studies (23). Furthermore, it is recommended to monitor important physiological parameters to maximize the benefits of HFOV as rescue therapy. These physiological parameters include lung recruitment, excess right ventricular afterload, decreased cardiac preload and cardiac output, and excess pulmonary stress and strain (5). For the assessment of lung recruitment, it is important to evaluate improvement in PaO2/FiO2 within the first three hours of HFOV application (34), in addition to using lung ultrasonography for its high specificity and sensitivity in lung collapse detection (35).

As for excess right ventricular afterload, transesophageal echocardiography is used for assessment and monitoring of right ventricular function (36). Measurement of cardiac output in response to passive leg raising is used to assess intravascular volume status and fluid responsiveness before applying HFOV (37), in addition to markers of hemodynamic assessment of tissue perfusion that include mixed venous oxygenation, central venous–arterial carbon dioxide difference, as well as lactate levels to evaluate cardiac preload and cardiac output (38). It is also important to measure transpulmonary pressure as an indicator of pulmonary stress and strain. For measurement of transpulmonary pressure, an esophageal catheter is positioned to measure the esophageal pressure, which is clinically used as a surrogate for intrathoracic pressure or pleural pressure, and the transpulmonary pressure is calculated. The aim is to prevent significant atelectrauma and maintain lung volume at less than total lung capacity to avoid overdistention of alveoli and the cyclical derecruitment of lung parenchyma, which are associated with VILI (39).

Conclusion

Without doubt, HFOV is effective for oxygenation improvement, which has been confirmed in several clinical trials conducted on pediatric and adult patients. Therefore, HFOV should be considered as rescue therapy in clinical situations in which severe or refractory hypoxemia is thought to be life-threatening. Cardiorespiratory function and other physiological responses to HFOV should be monitored closely and the risk of barotrauma and hemodynamic impairment should be considered. Clinicians should integrate this information with guidance from previously published protocols for safe titration of HFOV.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Non applicable.

Data availability

All data is available within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.