Volume 6, Issue 1

January 2026

Safety and Efficiency of Thulium Fiber Laser Versus Holmium: YAG in Stone Fragmentation Procedures: A Systematic Review

Shahirah Azzuz, Ahmed Alghamdi, Mohammed Alkhaldi, Mahmood Alqunais, Abdulrahman Binsaleh, Hassan Busaleh, Emad Al-Otaibi

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2026.60113

Keywords: Thulium Fiber Laser (TFL), Holmium: YAG laser (Ho:YAG), Stone fragmentation, Stone-free rate, Complications, Ablation efficiency, Operative time

Background: Laser lithotripsy has revolutionized the treatment of urinary stone disease, with Holmium: Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet (Ho: YAG) consistently recognized as the gold standard. The advent of the thulium fiber laser (TFL) has presented a new alternative with possible technological and therapeutic advantages. This systematic review aimed to compare the safety and efficacy outcomes of Thulium Fiber Laser (TFL) versus Ho: YAG laser in urinary stone fragmentation procedures. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect to identify English-language studies reporting outcomes related to operative time, stone-free rates, ablation efficiency, retropulsion, and endoscopic visibility in endourological stone management. Study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were performed independently by two reviewers. Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-randomized studies and the Cochrane risk of bias tool assessment for randomized trials. TFL requires less operative time when treating stones of moderate size. Nevertheless, several studies found no statistically meaningful difference between techniques, indicating that the benefit may vary according to stone size. Lasing times varied across studies, indicating that laser-on time alone may not fully reflect procedural efficiency. Stone-free rates were comparable or higher with TFL, with significant improvements observed for stones measuring 1–2 cm, while outcomes were similar for smaller stones or cohorts with high baseline clearance. Safety profiles were largely equivalent, with comparable overall complication rates. TFL was often associated with improved intraoperative visibility and reduced stone retropulsion, while isolated reports of infectious complications were inconsistent. TFL appears to be a safe and effective alternative to Ho: YAG for stone fragmentation, offering potential advantages in operative efficiency, stone clearance, retropulsion control, and energy utilization, particularly in selected patients with small to medium-sized stones. Both laser technologies demonstrated comparable safety, supporting their continued use in endourological practice.

Introduction

For decades, Holmium: Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet (Ho: YAG) lasers have served as the cornerstone of endourological lithotripsy; nevertheless, several inherent technical shortcomings limit their overall effectiveness. These include inefficient conversion of laser energy to stone ablation, substantial backward displacement of stones during firing, the need for relatively thick laser fibers, and constraints on pulse repetition rates. Collectively, these factors can compromise fragmentation efficiency, prolong operative time, and reduce maneuverability and precision during endoscopic interventions (1-3).

To address these limitations, next-generation laser platforms have been introduced with the aim of enhancing both clinical performance and operator control. Among these, the Thulium Fiber Laser (TFL) represents a significant advancement, utilizing a wavelength near 1940 nm that offers superior water absorption and permits the use of smaller-caliber fibers, thereby improving flexibility and access within the urinary tract. In parallel, novel pulse-modulated Ho: YAG systems such as Moses™, Virtual Basket™, and Magneto™ have been developed to alter pulse architecture, facilitating more efficient energy delivery to the stone while reducing retropulsion and improving fragmentation control during lithotripsy (4, 5)

The TFL has demonstrated superior performance over traditional Ho: YAG systems by achieving more rapid stone ablation, generating smaller and more uniform fragments, and producing reduced stone retropulsion. These advantages are largely explained by its increased affinity for water, more consistent energy output, and the ability to operate at substantially higher pulse frequencies. In addition, the smaller diameter of TFL fibers enhances endoscopic maneuverability, improves irrigation flow, and facilitates greater flexibility during ureteroscopy and retrograde intrarenal surgical procedures (6, 7).

The objective of this systematic review was to compare the safety and efficiency of TFL versus Ho: YAG laser in stone fragmentation procedures by evaluating perioperative complications and key efficiency outcomes, including operative time, stone-free rate, ablation performance, retropulsion, and endoscopic visibility during endourological interventions

Methods

Study design

This systematic review study, conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (8).

Definition of outcomes and inclusion criteria

Eligible studies were those conducted in human subjects undergoing laser lithotripsy or stone fragmentation that provided a direct comparison between TFL and Ho: YAG lasers and reported at least one measure of safety (e.g., complications or adverse events) and/or effectiveness (such as operative duration, stone-free rates, ablation performance, retropulsion, or endoscopic visibility). Eligible study designs: randomized trials, prospective or retrospective studies, and cohort or case–control studies with extractable data. Studies were excluded if they were non-comparative, in vitro or animal studies, case reports, editorials, letters, narrative reviews, or conference abstracts.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Science Direct to identify relevant studies evaluating the safety and efficiency of TFL versus Ho:YAG in stone fragmentation procedures. The search strategy used Boolean operators and controlled vocabulary where applicable, combining terms related to the laser technologies and stone disease as follows: (“Thulium Fiber Laser” OR TFL OR “Thulium laser”) AND (“Holmium:YAG” OR Ho:YAG OR “Holmium laser”) AND (“urolithiasis” OR “urinary stone*” OR “kidney stone*” OR “ureteral stone*” OR nephrolithiasis OR lithotripsy OR “stone fragmentation”) AND (“safety” OR complication OR “adverse event” OR efficiency OR efficacy OR “ablation rate” OR “operative time” OR “stone-free rate” OR retropulsion OR visualization). The search was restricted to studies involving human subjects and published in English, without applying any limits on the year of publication.

Screening and Extraction

Studies with irrelevant titles were excluded at the initial screening stage. Next, abstracts and full texts were carefully examined to assess eligibility according to the predefined inclusion criteria. Titles and abstracts were systematically compiled, evaluated, and checked for duplicate records using reference management software (EndNote X8). To enhance the rigor of the selection process, a two-step screening strategy was implemented: the first focused on reviewing titles and abstracts, while the second involved an in-depth assessment of the complete manuscripts. After finalizing the eligible studies, a standardized data extraction form was developed to collect information relevant to the study objectives.

Quality Assessment

In our systematic review, we employed the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) as a critical tool for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies included in our analysis (9). We assess the risk of bias in RCT studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs (10).

Results

Search Results

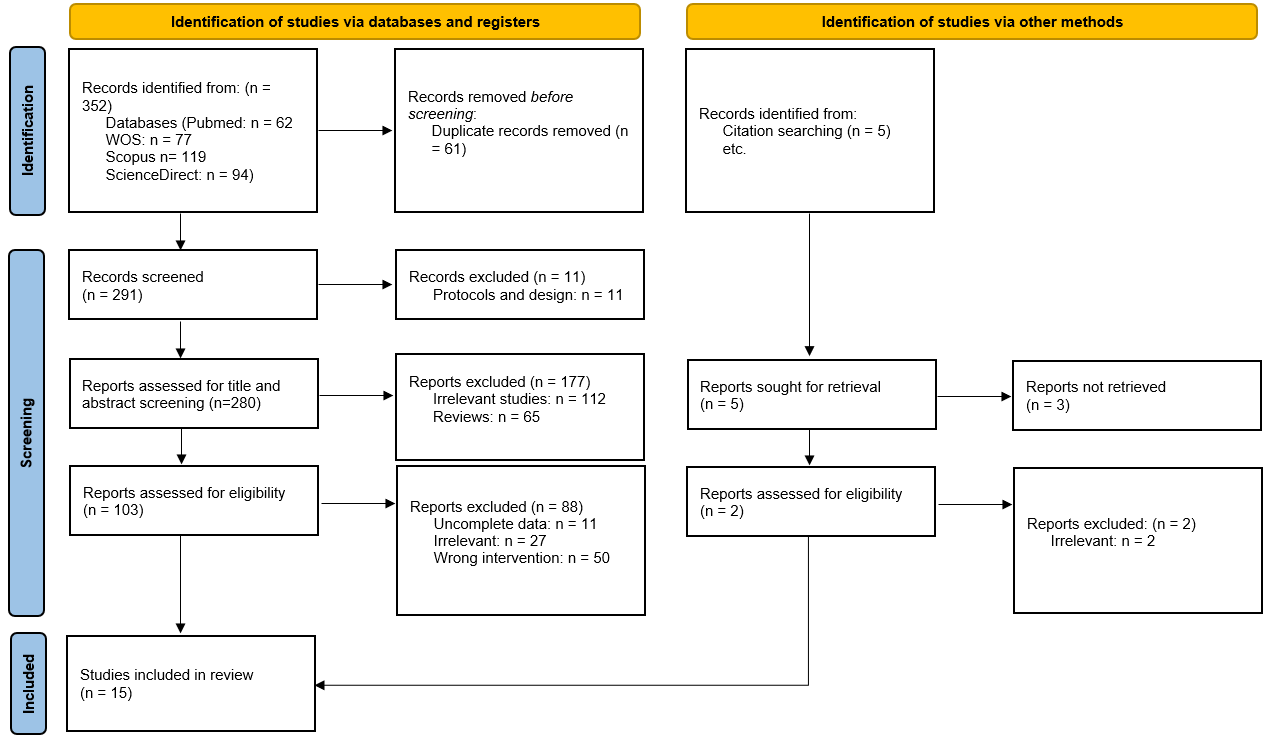

The predefined search strategies were applied, yielding 352 records initially. After eliminating duplicate entries, 291 unique citations remained. 103 potential eligible studies are included for full-text screening. Following a detailed full-text evaluation, the final selection consisted of 15 articles (11-25) aligning with our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Figure 1 provides the PRISMA flow chart.

Baseline characteristics

A total of 15 studies comprising both RCTs and cohort studies were included, enrolling patients undergoing ureteroscopy or retrograde intrarenal surgery for urinary stone disease. Overall, the sample size was larger in the TFL group, ranging from 32 to 1,567 patients, compared with 28 to 508 patients in the holmium: YAG laser group. Across most studies, the majority of participants were male, with the proportion of males generally ranging from 32.4% to 75.5% in the TFL group and 34.5% to 80% in the holmium group, indicating comparable sex distributions between treatment arms. The mean age of patients was broadly similar between groups, predominantly involving middle-aged to older adults. Reported mean ages ranged from approximately 38 to 61 years in the TFL group and 40 to 62 years in the holmium group. One study exclusively included pediatric patients. Baseline stone size was also largely comparable between the two modalities. The mean stone size generally ranged from approximately 10 to 13 mm in both groups, although some studies included larger stones, with mean sizes exceeding 20 mm (Table 1).

|

Table 1: The characteristics of the included studies |

||||||||

|

Study ID |

Design |

Population |

Sample size |

Male, n (%) |

Age, mean (SD) |

|||

|

Thulium |

Holmium |

Thulium |

Holmium |

Thulium |

Holmium |

|||

|

Castellani et al., 2023 (11) |

Cohort |

Adults undergoing retrograde intrarenal surgery for Kidney Stones |

1567 |

508 |

1074 (69) |

332 (65) |

46.4 (15.6) |

58.4 (15.6) |

|

Chai et al., 2024 (12) |

Cohort |

Patients undergoing retrograde intrarenal surgery for Kidney Stones |

318 |

415 |

103 (32.4) |

143 (34.5) |

45.4 (15.4) |

50.1 (16.5) |

|

Chandramohan et al., 2023 (13) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing ureteroscopic lithotripsy |

90 |

90 |

68 (75.5) |

70 (77.7) |

38.4 (12.2) |

40.3 (10.4) |

|

Delbarre et al., 2023 (14) |

Cohort |

Patients undergoing laser lithotripsy for the treatment of upper urinary tract lithiasis |

100 |

76 |

43 (43) |

43 (56.6) |

60.1 (17.7) |

57 (18.2) |

|

Gupta et al., 2024 (15) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing ureteric stone management with semi-rigid ureteroscopy |

40 |

40 |

25 (62.5) |

32 (80) |

44.93 (14.11) |

47.72 (12.88) |

|

Haas et al., 2023 (16) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing ureteroscopy of nonstaghorn stones <2 cm |

56 |

52 |

26 (46) |

31 (60) |

60.4 (12.9) |

61.6 (11.4) |

|

Kudo et al., 2025 (17) |

Cohort |

Patients undergoing retrograde intrarenal surgery for ureteral and renal stones |

48 |

48 |

35 (72.9) |

34 (70.8) |

60.4 (14.5) |

57.9 (27.5) |

|

Kozubaev et al 2025 (18) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing retrograde intrarenal surgery for kidney stone treatment |

64 |

62 |

42 (65.6) |

39 (62.9) |

47.45 (16.35) |

50.93 (13.78) |

|

Jaeger 2022 et al. (19) |

Cohort |

Pediatric patients undergoing unilateral ureteroscopies |

32 |

93 |

15 (47) |

36 (39) |

15.6 |

|

|

Martov 2020 et al (20) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing ureterolithotripsy |

87 |

87 |

50 (57) |

48 (55) |

48.1 (5.2) |

46.4 (4.3) |

|

Ryan et al., 2022 (21) |

Cohort |

Patients undergoing ureteroscopy lithotripsy |

51 |

51 |

25 (49) |

31 (60.8) |

NR |

NR |

|

Taratkin et al., 2023 (22) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing retrograde intrarenal surgery |

32 |

28 |

NR |

NR |

51.2 (14.1) |

53.4 (15.1) |

|

Ulvik et al., 2022 (23) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing ureteroscopic lithotripsy |

60 |

60 |

38 (63) |

39 (65) |

53 (22.8) |

54.4 (14.4) |

|

Bulut et al., 2025 (24) |

Cohort |

Patients undergoing ureteroscopy lithotripsy |

102 |

197 |

57 (55.9) |

101 (51.3) |

41.4 (13.8) |

43.7 (14.3) |

|

Gupta et al., 2025 (25) |

RCT |

Patients undergoing retrograde intrarenal surgery |

33 |

33 |

23 (70) |

25 (76) |

61.3 (13.6) |

59 (20.5) |

Operative Time

Across the included studies, TFL generally demonstrated an advantage in reducing operative time compared with Ho:YAG, although results were not entirely uniform. Several studies reported a statistically significant reduction in operative time with TFL, including Chandramohan et al. (2023) (13), Ryan et al. (2022) (21), Martov et al. (2020) (20), and Ulvik et al. (2022) (23). The magnitude of reduction was clinically relevant, ranging from approximately 8 to 13 minutes, with Ryan et al. showing even greater benefits in patients with smaller stone burdens (<15 mm and <10 mm), suggesting that stone size may modify the effect.{C}{C}

In contrast, multiple studies including Hass et al. (2023) (16), Castellani et al. (2023) (11), Chai et al. (2024) (12), Gupta et al. (2024) (15), and Kudo et al. (2025) (17) reported no significant difference in operative time between the two laser modalities. Delbarre et al. (2023) (14) further highlighted that the advantage of TFL may be stone-size dependent, with shorter operative times observed only for stones measuring 1–2 cm, while outcomes were comparable for smaller and larger stones (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Operative Time |

|

|

Study |

Key Findings |

|

Chandramohan et al., 2023 (13) |

Mean operative time was significantly shorter with TFL (18.5 ± 1.5 min) vs Ho:YAG (31.6 ± 1.2 min), P = 0.024. |

|

Ryan et al., 2022 (21) |

TFL reduced operative time by 12.9 min per case vs Ho:YAG (P = 0.021); greater reductions seen for stones <15 mm and <10 mm. |

|

Martov et al., 2020 (20) |

Total operation time was longer in Ho:YAG vs TFL (32.4 ± 0.7 vs 24.7 ± 0.7 min, P < 0.05). |

|

Hass et al., 2023 (16) |

No significant difference in ureteroscope time between Ho:YAG (21 min) and TFL (19.9 min). |

|

Castellani et al., 2023 (11) |

Total operative time was similar between TFL and Ho:YAG. |

|

Chai et al., 2024 (12) |

Operation times were comparable between TFL and Ho:YAG groups. |

|

Kudo et al., 2025 (17) |

No significant difference in operative time (45 vs 54 min, P = 0.10). |

|

Delbarre et al., 2023 (14) |

Operative time was shorter with TFL for stones 1–2 cm; similar for <1 cm and >2 cm stones. |

|

Gupta et al., 2024 (15) |

Mean operative time was comparable between TFL and Ho:YAG. |

|

Ulvik et al., 2022 (23) |

Operative time was shorter with TFL (49 min) vs Ho:YAG (57 min), P = 0.008. |

TFL: Thulium Fiber Laser; Ho:YAG: Holmium:Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet laser

Lasing / Laser Time

The findings regarding lasing (laser-on) time demonstrate heterogeneous results across studies comparing TFL and Ho:YAG lasers. Several studies suggest a potential advantage of TFL in reducing lasing time, most notably Chandramohan et al. (2023) (13), which reported a significantly shorter lasing duration with TFL compared to Ho:YAG. Similarly, Martov et al. (2020) (20) observed longer lasing times in the Ho:YAG group, indirectly favoring TFL.

However, this trend was not consistently observed across all studies. Jaeger et al. (2022) (19) reported longer median laser time with TFL compared with Ho:YAG, although this did not translate into a longer total operative time, suggesting that increased laser-on time may be offset by efficiencies in other procedural steps. Several randomized and comparative studies, including Gupta et al. (2025) (25), Kudo et al. (2025) (17), and Gupta et al. (2024) (15), found no statistically significant differences in lasing time between the two modalities.

Taratkin et al. (2023) (22) further emphasized the influence of laser settings and fiber characteristics, reporting shorter laser-on time with Ho:YAG compared to SP TFL using a 150-µm fiber, despite Ho:YAG requiring significantly higher total energy consumption. This indicates that lasing time alone may not fully capture laser efficiency and should be interpreted alongside energy use, ablation efficiency, and clinical outcomes (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Lasing / Laser Time |

|

|

Study |

Key Findings |

|

Chandramohan et al., 2023 (13) |

Lasing time was significantly shorter with TFL (7.4 ± 1.8 min) vs Ho:YAG (14.8 ± 1.5 min), P = 0.011. |

|

Martov et al., 2020 (20) |

Lasing time was longer in the Ho:YAG group. |

|

Jaeger et al., 2022 (19) |

Median laser time was longer with TFL (11 min) vs Ho:YAG (2 min), but total operative time was similar. |

|

Gupta et al., 2025 (25) |

Lasing time was similar between TFL and Ho:YAG (9.4 vs 12.8 min, P = 0.3). |

|

Kudo et al., 2025 (17) |

No significant difference in laser time (15 vs 10 min, P = 0.12). |

|

Taratkin et al., 2023 (22) |

Laser-on time was significantly shorter with Ho:YAG vs SP TFL 150-µm fiber, but Ho:YAG used more total energy. |

|

Gupta et al., 2024 (15) |

Mean total lasing time was comparable between groups. |

TFL: Thulium Fiber Laser; Ho:YAG: Holmium:Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet laser; SP-TFL: SuperPulsed Thulium Fiber Laser

Stone-Free Rate (SFR)

Overall, the evidence suggests that TFL is associated with equal or superior SFR compared with Ho:YAG, although results vary across studies. Several investigations demonstrated a significantly higher SFR with TFL, including Martov et al. (2020) (20), which reported no residual stones in the TFL group at 30-day follow-up, and Ulvik et al. (2022) (23), which showed a markedly higher SFR with TFL (92% vs 67%). Similarly, Castellani et al. (2023) (11) and Jaeger et al. (2022) (19) reported substantially improved stone clearance with TFL, with Jaeger et al. showing a 61% reduction in the odds of residual stones. Chai et al. (2024) (12) further supported this finding by demonstrating that TFL independently predicted stone-free status on multivariable analysis.

In contrast, some studies found no statistically significant difference in SFR between the two laser modalities. Hass et al. (2023) (16), Gupta et al. (2025) (25), Kudo et al. (2025) (17), and Gupta et al. (2024) (15) reported comparable stone-free outcomes, particularly in cohorts with smaller stones or high baseline clearance rates. Delbarre et al. (2023) (14) highlighted a stone-size–dependent effect, with TFL showing higher SFR only for stones measuring 1–2 cm, while outcomes were similar for smaller (<1 cm) and larger (>2 cm) stones (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Stone-Free Rate |

|

|

Study |

Key Findings |

|

Martov et al., 2020 (20) |

No residual stones at 30 days in the TFL group vs 5 cases in Ho:YAG. |

|

Jaeger et al., 2022 (19) |

Higher SFR with TFL (70%) vs Ho:YAG (59%); TFL reduced odds of residual stones by 61%. |

|

Hass et al., 2023 (16) |

No significant difference in stone-free rates between TFL and Ho:YAG. |

|

Gupta et al., 2025 (25) |

Absolute SFR was similar (82% TFL vs 79% Ho:YAG, P = 0.8). |

|

Castellani et al., 2023 (11) |

Higher SFR with TFL (85%) vs Ho:YAG (56%), P < 0.001. |

|

Chai et al., 2024 (12) |

Overall SFR was higher in the TFL group; TFL independently predicted stone-free status. |

|

Kudo et al., 2025 (17) |

Stone-free rates were similar (97.9% TFL vs 95.8% Ho:YAG). |

|

Delbarre et al., 2023 (14) |

Overall SFR was similar; TFL showed higher SFR for stones 1–2 cm. |

|

Gupta et al., 2024 (15) |

SFR at 1 month was slightly higher with TFL (100% vs 90%), not statistically significant. |

|

Ulvik et al., 2022 (23) |

SFR was significantly higher with TFL (92%) vs Ho:YAG (67%), P = 0.001. |

TFL: Thulium Fiber Laser; Ho:YAG: Holmium:Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet laser; SFR: Stone-Free Rate; OR: Odds Ratio.

Complications & Safety

Across most included studies, TFL and Ho:YAG demonstrated comparable safety profiles, with no significant differences in overall complication rates. Multiple studies including Jaeger et al. (2022) (19), Hass et al. (2023), Gupta et al. (2025) (25), Chai et al. (2024) (12), Kudo et al. (2025) (17), and Delbarre et al. (2023) (14) consistently reported similar rates of postoperative complications, emergency department visits, ureteral injuries, postoperative fever, and length of hospital stay between the two laser modalities. These findings suggest that both technologies are generally safe and well tolerated in routine clinical practice.

Notably, certain procedure-specific adverse events differed between groups. Ulvik et al. (2022) (23) reported a significantly higher rate of intraoperative bleeding impairing endoscopic vision in the Ho:YAG group compared with TFL, indicating a potential advantage of TFL in maintaining intraoperative visibility. Conversely, Castellani et al. (2023) (11) observed sepsis exclusively in the TFL group, raising concerns regarding infectious complications in that cohort; however, this finding contrasts with the broader literature and may reflect confounding factors such as patient selection, procedural complexity, or institutional practices (Table 5).

|

Table 5: Complications & Safety |

|

|

Study |

Key Findings |

|

Jaeger et al., 2022 (19) |

Postoperative complication rates were similar between groups. |

|

Hass et al., 2023 (16) |

No differences in complications between TFL and Ho:YAG. |

|

Gupta et al., 2025 (25) |

Emergency visits and complication rates were similar. |

|

Castellani et al., 2023 (11) |

Sepsis occurred in 9 TFL patients vs none in Ho:YAG. |

|

Chai et al., 2024 (12) |

Postoperative complications and hospital stay were similar. |

|

Kudo et al., 2025 (17) |

No differences in ureteral injury or postoperative fever. |

|

Delbarre et al., 2023 (14) |

Complication rates were comparable between groups. |

|

Ulvik et al., 2022 (23) |

Intraoperative bleeding impairing vision was more frequent with Ho: YAG (22% vs 5%), P = 0.014. |

TFL: Thulium Fiber Laser; Ho:YAG: Holmium: Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet laser

Laser Efficiency, Vision, and Retropulsion

The evidence regarding laser efficiency, endoscopic vision, and retropulsion suggests a potential technical advantage of TFL, although findings are not entirely consistent across studies. Chandramohan et al. (2023) (13) reported superior laser efficacy and higher ablation speed with TFL compared with Ho:YAG, indicating more efficient stone fragmentation; however, this study also found better visual scores with Ho:YAG, highlighting that improved ablation efficiency does not necessarily translate into superior intraoperative visibility.

In contrast, Gupta et al. (2025) (25) found no significant differences between TFL and Ho:YAG in terms of laser ablation efficiency or ablation speed, suggesting that when comparable laser settings and techniques are used, the two modalities may perform similarly. Gupta et al. (2024) (15) provided additional nuance by demonstrating better endoscopic vision and significantly reduced retropulsion with TFL, which may facilitate more controlled fragmentation and reduce the need for stone repositioning during the procedure.

Taratkin et al. (2023) (22) further supported the efficiency of TFL by showing that Ho:YAG required significantly higher total energy consumption than SP TFL to achieve comparable outcomes, implying greater energy efficiency with TFL despite variable laser-on times (Table 6).

|

Table 6: Laser Efficiency, Vision, and Retropulsion |

|

|

Study |

Key Findings |

|

Chandramohan et al., 2023 (13) |

Laser efficacy and ablation speed were better with TFL; visual score was better with Ho:YAG. |

|

Gupta et al., 2025 (25) |

No significant differences in laser ablation efficiency or speed. |

|

Gupta et al., 2024 (15) |

Vision was better and retropulsion was less with TFL. |

|

Taratkin et al., 2023 (22) |

Total energy consumption was significantly higher with Ho:YAG than SP TFL. |

TFL: Thulium Fiber Laser; Ho:YAG: Holmium:Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet laser; SP-TFL: SuperPulsed Thulium Fiber Laser

Quality assessment

The risk of bias varied across the included studies. Most trials showed a low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data and other bias, indicating generally good handling of attrition and no major additional methodological concerns. Selective reporting was also mostly low risk, suggesting outcomes were reported as prespecified.

However, blinding of participants and personnel was frequently rated as high risk, likely due to the interventional nature of the studies, while blinding of outcome assessment was often unclear because of insufficient reporting. Random sequence generation and allocation concealment were adequate in some studies but unclear or high risk in others, indicating potential selection bias.

Overall, the evidence is of moderate methodological quality, with a few studies demonstrating consistently low risk of bias, while others showed limitations mainly related to blinding and reporting (Table 7).

|

Table 7: Cochrane Risk Assessment |

|||||||

|

Studies |

Random sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding of participants and personnel |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective reporting |

Other bias |

|

Martov et al., 2021 (20) |

Unclear |

High |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

|

Ulvik et al., 2022 (23) |

Low |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Chandramohan et al., 2023 (13) |

Low |

High |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

|

Haas et al., 2023 (16) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Taratkin et al., 2023 (22) |

Low |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Gupta et al., 2024 (15) |

Low |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

|

Gupta et al., 2025 (25) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Kozubaev 2025 (18) |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

The non-randomised retrospective studies demonstrated good overall methodological quality based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. All studies achieved the maximum score for selection, indicating appropriate case definition and representativeness. Scores for comparability ranged from 1 to 2, suggesting that most studies adequately controlled for important confounding factors, although adjustment was limited in some.

The outcome domain was generally strong, with most studies scoring 2–3 points, reflecting reliable outcome assessment and sufficient follow-up. Overall NOS scores ranged from 8 to 9 out of 9, indicating a low risk of bias and supporting the robustness of the evidence derived from these retrospective studies (Table 8).

|

Table 8: Quality assessment of non-randomised retrospective studies using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) |

||||

|

Study |

Selection |

Comparability |

Outcome |

Total |

|

Jaeger et al., 2022 (19) |

4 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

|

Ryan et al., 2022 (21) |

4 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

|

Castellani et al., 2023 (11) |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

|

Delbarre et al., 2023 (14) |

4 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

|

Chai et al., 2024 (12) |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

|

Kudo et al., 2025 (17) |

4 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

|

Bulut et al., 2023 (24) |

4 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this systematic review, TFL generally matched or exceeded Ho:YAG performance across key efficacy and safety metrics. Operative times tended to be shorter with TFL especially for stones in the 1–2 cm range while stone-free rates (SFRs) were at least equivalent and often higher with TFL. For example, our review found significantly better clearance for 1–2 m stones with TFL, whereas outcomes were similar for very small stones (e.g. <1 cm) or when baseline clearance was already high. Lasing (“laser-on”) times varied among studies and did not consistently favor either laser, indicating that total laser time alone may not capture clinical efficiency. TFL also showed technical advantages as it produced less stone retropulsion and in many series was associated with improved endoscopic visibility (likely due to smaller fiber size and higher water absorption). Safety profiles were largely comparable, with no consistent differences in overall complication rates. In rare instances a few studies reported unexpected findings (for example, a higher rate of postoperative fever/sepsis with TFL in one series), but these were not replicated in other cohorts. Notably, bleeding impairing vision appeared more common with Ho:YAG in at least one study, consistent with the enhanced irrigation flow and smaller fibers of TFL. In sum, this review suggests that TFL is a safe, effective alternative to Ho:YAG, with potential efficiency gains (shorter procedures, and higher clearance in medium stones) and reduced retropulsion as the main benefits.

Investigation with prior literature

These results are broadly in line with prior literature. Several recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews report similar advantages for TFL. Tang et al. (26) pooled 13 studies and found that TFL produced significantly higher SFRs and shorter operating times than Ho:YAG, as well as markedly less stone migration (retropulsion). Uleri et al. (27) similarly observed that TFL was associated with a higher SFR (particularly for renal stones) and a lower intraoperative complication rate, although total operative and lasing times did not differ significantly. In subgroup analyses by stone location, Uleri et al. (27) reported a much higher clearance rate with TFL for kidney stones, but no advantage for ureteral stones, echoing our finding that TFL’s benefit may be most pronounced in renal rather than ureteric stones. Bhardwaj et al. (28) reviewed eight clinical studies and likewise found that TFL achieved similar or slightly higher SFRs (82–98% vs. 56–95% with pulse-modulated Ho:YAG) and comparable operative times; importantly, TFL showed less retropulsion and better endoscopic visibility, with an equivalent complication profile. Ali et al. (29) analyzed 13 trials and noted that while overall SFRs were comparable, many individual reports favored TFL (with higher clearance and shorter operative times) and consistently showed improved “dusting” performance and ergonomics (due to higher frequency and smaller fibers) with TFL. These findings reinforce our results: multiple independent analyses conclude that TFL is at least non-inferior to Ho:YAG and often superior in fragmenting efficiency and intraoperative control.

Clinical implications

Our findings suggest nuanced guidance for endourologic practice. In general, either laser can achieve high SFRs and acceptable safety. When choosing between technologies, surgeons may consider specific scenarios where TFL’s advantages are most relevant. For stones of small volume (e.g. <1 cm), both lasers typically achieve excellent clearance, so either is acceptable. However, for medium-sized stones (1–2 cm) especially in challenging anatomic locations, TFL appears to offer meaningful benefit. Delbarre et al. (14) found that TFL yielded significantly higher stone-free rates and shorter operating times for 1–2 cm stones, whereas results were similar for <1 cm stones. Likewise, our review noted that the most consistent superiority of TFL was seen in this size range. This suggests that in routine ureteroscopy or retrograde intrarenal surgery for 1–2 cm stones, TFL may be preferred, as it can ablate faster and reduce retropulsion (thus minimizing basket passes).

Stone location also matters. As Uleri et al. (27) reported, TFL’s higher SFR was confined to renal stones; for ureteral stones, no significant difference in clearance was found. Thus, for proximal stones where maneuverability and irrigation are limited, TFL’s smaller fiber (allowing greater deflection and flow) could confer an advantage. In contrast, simple ureteric stones may be equally managed by either laser, and pneumatic or ultrasonic devices remain options for larger burden. Notably, some authors suggest that TFL might even expand the scope of ureteroscopic treatment for very large stones. Delbarre et al. (14) hypothesized that TFL could expand ureteroscopy indications for stones >2 cm, given its improved dusting capability, though percutaneous nephrolithotomy (typically Ho:YAG-powered) remains the standard for such cases.

Anatomical considerations also favor TFL in certain contexts. The smaller-caliber fiber enhances endoscope deflection and irrigation, which may improve access to lower-pole or calyceal stones. Less retropulsion can help maintain stone fragments in line-of-sight, potentially reducing fluoroscopy and scope adjustments. In cases where endoscopic visibility is otherwise challenged (e.g. bleeding, narrow ureter), TFL’s smaller fiber and more constant energy may improve vision; indeed, some studies in our review reported better vision scores with TFL. On the other hand, power limitations (most current TFL systems are up to 60W) mean that for very dense stones or continuous ablation (e.g. mini-PCNL with thick cortex), high-power Ho:YAG may still be effective. Surgeon preference and experience are factors too; centers heavily invested in Moses® pulse-modulated Ho:YAG may find its performance adequate. Indeed, expert guidance suggests that upgrading from a high-performance Ho:YAG should be driven by case complexity, budget, and caseload rather than by an expectation of radical superiority of TFL (28).

From a practical standpoint, both lasers proved safe in our review. We saw no evidence of unique hazards with TFL: intraoperative ureteral injury and post-operative complications were similar between groups. Some authors have observed minor trends (e.g. slightly fewer bleeding events with TFL, but overall complication rates did not differ. Therefore, endourologists can consider TFL as a drop-in alternative for stone lithotripsy. In settings prioritizing dusting and minimal retropulsion as pediatric cases, lower-pole calculi, or patients with high risk of ureteral trauma, TFL may be especially appealing. However, it should be emphasized that either modality can achieve excellent outcomes when used judiciously. In the absence of definitive superiority, cost, availability, and surgeon experience will remain important determinants of laser choice.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review has several advantages. It synthesized 15 studies (randomized and cohort) encompassing thousands of patients undergoing ureteroscopic or intrarenal stone surgery. The included studies spanned a range of stone sizes and clinical settings (mean stone sizes ~10–13 mm, with some studies including stones >20 mm), thereby capturing heterogeneity relevant to real-world practice. Rigorous methodology was applied: searches of multiple databases, dual independent screening and data extraction, and formal quality assessment (using Cochrane risk-of-bias for RCTs and Newcastle–Ottawa for observational studies) were performed. The review followed PRISMA guidelines, minimizing selection bias. By focusing on both efficacy (time, SFR, and energy) and safety (complications, and visibility), the review provides a balanced appraisal of TFL vs Ho:YAG. Furthermore, inclusion of recent high-quality studies (including multicenter analyses and propensity-matched cohorts) gives the findings contemporary relevance. Several limitations must temper our conclusions. First, there was substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity among the included studies. Laser settings (power, pulse duration, and frequency) and fiber diameters varied widely across reports, making direct comparisons difficult. Different studies also used different Ho:YAG platforms (standard vs Moses®) and TFL modes (continuous vs super-pulse), which can affect performance. Procedures ranged from simple ureteroscopy to flexible retrograde intrarenal surgery and even mini- percutaneous nephrolithotripsy; such procedural diversity, as well as variable surgeon experience, likely contributed to the inconsistent findings on operative time and laser time. Second, outcome definitions were not uniform. Studies differed in follow-up duration and imaging modality for assessing stone clearance (from immediate fluoroscopy to CT at 3 months). “Stone-free” criteria (any fragments vs <2–3 mm fragments) also varied. These inconsistencies limit quantitative synthesis and may inflate apparent SFR differences in some series. Third, many studies were retrospective or single center, introducing potential bias; only a minority were randomized. For example, most data on TFL come from early adopters, which could lead to publication bias toward favorable results. Fourth, patient and stone characteristics were sometimes uneven between groups. Finally, we did not evaluate economic factors. TFL systems have different cost and maintenance profiles than Ho:YAG units, and these practical aspects were beyond the scope of our analysis.

Recommendations and future research

Given the promising but still emerging data, several steps are warranted. Future studies should use standardized protocols: ideally large multicenter randomized trials directly comparing modern high-power TFL and pulse-modulated Ho:YAG (e.g. Moses 2.0) under the same energy settings. Consistent definitions of stone-free status, operative time (e.g. including scope worktime vs laser-on time), and other endpoints (including retropulsion quantification and visibility scores) are needed to enable meta-analysis. Research should also examine thermal safety (e.g. intrarenal temperature monitoring) and fiber durability, as these practical factors affect clinical use. Cost-effectiveness analyses and long-term follow-up (retreatment rates, patient-reported outcomes) should be incorporated, since current evidence is largely short-term. Clinically, urologists may consider adopting TFL for standard ureteroscopic cases of moderate stone burden but should do so with awareness that long-term and real-world comparative data are still limited. Both lasers are safe and effective, and until further high-quality data are available, the choice can be tailored to the clinical scenario, resource availability, and surgeon experience.

Conclusion

Our systematic review converges on the view that TFL is an effective alternative to Holmium:YAG for urinary stone lithotripsy. TFL offers potential advantages in operative efficiency and stone clearance for certain patients, without compromising safety. However, these benefits are context-dependent and not universally seen in every study. Ongoing research should seek to delineate the precise niches where TFL adds value, and to standardize outcomes to guide practice. Meanwhile, both laser technologies remain valuable tools in the endourologist’s armamentarium.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Non applicable.

Data availability

All data is available within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.