Volume 5, Issue 12

December 2025

Barriers to Follow-Up After Initial Primary Care Visits: A Cross-Sectional Study

Hamdan Alshammari, Mohammed Saad Alqahtani, Suliman Abdullah Alaqeel, Abdulhakim Farhan Alharbi, Saif Daham Alshalan, Abdulmajeed Abdulrazaq Alzahrani , Ibrahim Saad Abuabat

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2025.51222

Keywords: primary care, follow-up visits, factors affecting adherence, barriers

Background: Barriers to effective follow-up appointments after an initial primary care visit include a complex mix of patient-related factors, socioeconomic constraints, and healthcare system and access issues. The goal of this study is to determine the prevalence of non-adherence to follow-up after initial primary care visits and to identify the barriers influencing follow-up attendance.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted at Hail Health Cluster primary care facility in Saudi Arabia in 2025 among adult patients who missed follow-up appointments within six months after their initial visit. Data was collected via the survey method. Patient barriers to follow-up were assessed across multiple domains: patients' perceptions of health beliefs and understanding, the healthcare system and access barriers domain, and the communication factors domain. Data analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0.

Results: This study analyzed follow-up appointment adherence among 120 adult participants, revealing that 68.33% attended their scheduled appointments. The main reasons for non-attendance were forgetfulness (34.17%) and feeling better (37.50%). Employment status (p = 0.012), educational status (p = 0.009), and monthly income (p = 0.004) significantly impacted follow-up attendance. Those who attended had higher health belief scores (16 vs. 14; p=0.030), and participants citing long wait times had higher odds of missing appointments (OR = 3.27; p = 0.020). Participants with lower monthly family income (<6,000 SAR) had significantly reduced odds of attending follow-up visits compared with those who did not report their income.

Conclusion: This study identified demographic, psychological, economic, and system-related factors influencing poor follow-up adherence in Saudi Primary care. Low income, low education, weak health beliefs, and long waiting times were major predictors of non-attendance. Healthcare system improvements may enhance adherence and care quality.

Introduction

Primary healthcare systems ensure accessible, egalitarian, and continuous medical treatment, with primary care physicians playing major roles in treating acute and chronic disorders (1). They serve as the initial point of contact for patients, addressing a wide range of health needs from common illnesses to long-term health management. Globally, health care systems emphasize primary care to enhance population health, health care quality, and health equality; reduce the clinical burden of secondary and tertiary care; and lower health care expenditure (2, 3). The World Health Organization promotes patient-centered, coordinated, and communicative care (4). However, many healthcare settings face difficulties that undermine care plans and negatively impact long-term health outcomes after the initial visit.

Regular follow-up appointments are necessary for managing non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and asthma; therefore, these conditions require consistent follow-ups of their patients (5). However, many patients encounter challenges in transitioning from primary consultation to follow-up visits. Missed appointments can disrupt continuity of care, limiting opportunities for preventive interventions, medication evaluations, and early detection of complications. Failure to follow up can lead to missed diagnoses, inadequate treatment, and progression of illness (6, 7). Primary care can be more effective when there is a clearer understanding of the interactions between the initial visit and follow-up consultations (8).

Previous studies have shown that several interrelated personal, socioeconomic, healthcare provider-related, and systemic factors impact follow-up appointment adherence (9). Patients' awareness about their illness, perceived wellness, spiritual beliefs, and motivation substantially influence follow-up adherence. Additionally, socioeconomic constraints like transportation cost, lower income, and lack of family support also emerged as key barriers (10, 11). Healthcare system-related barriers can also contribute to missed follow-up appointments, such as insufficient communication, lack of structured education, distance from PHCCs to rural residents, absence of a reminder system, lack of services, staff shortages, lack of training, PHC infrastructure, and poor equipment (9, 11). Dissatisfaction with prior treatment or perceived enhancement of symptoms may lead patients to decline follow-up appointments (12).

In Saudi Arabia, non-adherence to primary care follow-up visits remains a notable issue, with studies reporting appointment failure rates between 23% and 30% in Saudi Arabia's eastern and central regions (13, 14). In Saudi Arabian studies, patients' most prevalent reasons for missing follow-up appointments include forgetfulness, confusing appointment details, and logistical challenges, especially for women. Lack of knowledge of patients, crowdedness at PHCs, and busy staff at PHCs are reported as barriers that hamper the use of routine checkups (15). Understanding these patient-related, communication-related, and healthcare system-related barriers is crucial for tailoring effective therapies to this population.

Therefore, this cross-sectional study aims to investigate the barriers to follow-up appointments after primary care visits. The main goals for this study are to determine the prevalence of missed follow-up visits among primary care clinic patients, identify patient-reported barriers, patient health belief barriers, communication barriers, and healthcare system/access-related barriers to non-adherence to follow-up after initial visits, examine their association with sociodemographic factors, and develop evidence-based recommendations to improve follow-up adherence.

Methods

Study Design/Setting

This cross-sectional study was carried out at the Hail Health Cluster primary care facility in Saudi Arabia in 2025. The study comprised patients who were informed of a follow-up appointment subsequent to their initial visit to the PHC but did not attend the scheduled follow-up within a 6-month period. Ethical approval was obtained from the Hail Health Cluster Institutional Review Board (Approval No. 2025-90, dated 3 September 2025).

Study Population

The study included patients aged between 18 and 60 years old who were advised to attend a follow-up appointment after an initial visit to the PHC and failed to attend the scheduled follow-up within 6 months. Patients with trauma requiring urgent care and those arriving at the PHC via ambulatory services were excluded from the study. Patients who were referred to secondary or tertiary care facilities and those who completed their follow-up visits as scheduled were also omitted. Individuals with significant cognitive impairment, severe psychiatric disease, or language obstacles that hinder effective data collection and communication, as well as patients who declined to participate in the study and those whose survey replies were incomplete or inconsistent, were also excluded.

Sample Size Calculation and Sampling Method

The sample size for this cross-sectional study was calculated using OpenEpi (version 3.01). The required sample size was estimated using findings by Neal et al. (2005) (16), who demonstrated that 15.9% of primary care patients missed their follow-up appointments (p = 0.159). With 68% non-response rate or incomplete data, the target sample size was 386 participants. Data were collected from 211 participants, of which 91 were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 120.

Data Collection

We have developed a web-based, self-administered patient-reported survey questionnaire to evaluate the barriers to follow-up after primary care appointments. The questionnaire is based on a review of relevant literature and expert consultation and includes the following components:

The demographic and clinical information section obtained data on participants' age, gender, nationality, marital status, education level, employment status, health insurance coverage, and the presence of chronic health conditions, as well as details of appointment history. The barriers to follow-up attendance domain included a list of 10 predefined barrier options, and participants were asked to select all that apply. Health beliefs and understanding domain are assessed using four Likert-scale items to evaluate participants' beliefs regarding the importance and benefits of follow-up care, as well as their understanding of the consequences of non-attendance. The healthcare system and access barriers domain contain 8 yes/no questions related to logistical challenges such as difficulties in scheduling, inconvenient clinic hours, long travel distance, and other system-related barriers. The Communication and Reminders section explored whether participants received reminders, language barriers, and how reminders help them. Finally, participants were invited to provide suggestions through multiple-choice options and/or open-ended responses on how to enhance follow-up attendance, such as improved communication, flexible scheduling, or educational interventions.

The questionnaire, available in English and Arabic, showed acceptable reliability (Health Beliefs α = 0.608; System/Access Barriers α = 0.795) (17). Patients’ anonymity was maintained throughout all stages of data collection and analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses and calculations were conducted using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS, version 26, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were presented as median (IQR) and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages.

Internal consistency (reliability analysis) was measured using Cronbach's alpha. Follow-up attendance status was compared among demographic, clinical history, and other categorical factors using the chi-square or Fisher's exact test. To compare age, health belief scores, and system/access barrier scores, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. Binary logistic regression was used to predict the follow-up attendance status with significant demographics, clinical, health belief, and barrier factors. Presented results as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A p-value of less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

This study included a total of 120 adult participants. The median age of the study population was 33 (26 - 40.75) years, with a predominant male distribution (60% males and 40% females). All the patient demographic and clinical characteristics were explained in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Participant Characteristics and Appointment Attendance History |

||

|

Variable |

Category |

n (%) |

|

Gender |

Male |

72 (60.00) |

|

Female |

48 (40.00) |

|

|

Nationality |

Saudi |

120 (100.0) |

|

Employment Status |

Employed |

78 (65.00) |

|

Unemployed |

22 (18.33) |

|

|

Retired |

4 (3.33) |

|

|

Student |

16 (13.33) |

|

|

Marital Status |

Single |

46 (38.33) |

|

Married |

70 (58.33) |

|

|

Divorced |

2 (1.67) |

|

|

Widowed |

1 (0.83) |

|

|

Educational Level |

Elementary |

3 (2.50) |

|

High school |

28 (23.33) |

|

|

University |

72 (60.00) |

|

|

Postgraduate |

17 (14.17) |

|

|

Monthly Family Income (SAR) |

<3,000 |

14 (11.67) |

|

3,000–5,999 |

11 (9.17) |

|

|

6,000–9,999 |

13 (10.83) |

|

|

10,000–14,999 |

34 (28.33) |

|

|

15,000–19,999 |

22 (18.33) |

|

|

≥20,000 |

12 (10.00) |

|

|

Prefer not to say |

14 (11.67) |

|

|

Health Insurance Age, Median (IQR) |

No |

95 (79.17) |

|

Yes |

25 (20.83) |

|

|

33 (26 - 40.75) |

||

|

Reason for first visit to primary care |

Routine check-up |

23 (19.17) |

|

Preventative care |

4 (3.33) |

|

|

Chronic disease follow-up |

10 (8.33) |

|

|

New health problems |

8 (6.67) |

|

|

Attended Scheduled Follow-up |

No |

38 (31.67) |

|

Yes |

82 (68.33) |

|

|

Missed Appointments |

One |

18 (15.00) |

|

2-3 |

8 (6.67) |

|

|

More than 3 |

2 (1.67) |

|

|

Reason for Last Follow-up |

Case follow-up |

34 (28.33) |

|

Chronic disease management |

14 (11.67) |

|

|

Lab result discussion |

49 (40.83) |

|

|

Medication follow-up |

21 (17.50) |

|

|

Fever or other symptoms |

1 (0.83) |

|

SAR: Saudi Arabian Riyal

Prevalance of Missed Follow-up Visits and Follow-up Attendance Patterns

Most participants (68.33%) reported attending their scheduled follow-up appointments, whereas 31.67% did not attend, and 15% missed at least one follow-up session. The most prevalent cause for the last follow-up visit was lab result discussion (40.83%), followed by case follow-up (28.33%) and medication-related visits (17.50%) (Table 1).

Association Between Sociodemographic Factors and Follow-up Attendance

Employed individuals were more likely to attend follow-up appointments (73.17%) than unemployed individuals (10.98%), and there was a statistically significant association between employment status and scheduled follow-up attendance (p = 0.012). Additionally, there was a significant association (p = 0.009) between educational level and follow-up attendance, with university-level educated participants having the highest rate (64.63%). Monthly family income was another significant factor (p = 0.004), with lower-income groups (<6,000 SAR) having disproportionately higher non-attendance rates, while those earning ≥10,000 SAR had better follow-up attendance. Participants who attended follow-up appointments had significantly higher health belief scores compared to participants who did not attend the follow-up visits (16 (14-17.25) vs 14 (13-16); p=0.030) (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Follow up attendance vs. demographic factors |

||||

|

Scheduled follow-up appointment Attendance |

p value |

|||

|

No |

Yes |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

21 (55.26) |

51 (62.20) |

0.471 |

|

Female |

17 (47.74) |

31 (37.80) |

||

|

Employment status |

Employed |

18 (47.37) |

60 (73.17) |

0.012* |

|

Unemployed |

13 (34.21) |

9 (10.98) |

||

|

Retired |

1 (2.63) |

3 (3.66) |

||

|

Student |

6 (15.79) |

10 (12.20) |

||

|

Social Status |

Single |

15 (40.54) |

31 (37.80) |

0.850 |

|

Married |

21 (56.76) |

49 (59.76) |

||

|

Divorced |

1 (2.70) |

1 (1.22) |

||

|

Widowed |

0 (0.00) |

1 (1.22) |

||

|

Educational level |

Elementary |

3 (7.89) |

0 (0.00) |

0.009* |

|

High school |

13 (34.21) |

15 (18.29) |

||

|

University |

19 (50.00) |

53 (64.63) |

||

|

Postgraduate studies |

3 (7.89) |

14 (17.07) |

||

|

Monthly family income |

Less than 3,000 SAR |

10 (26.32) |

4 (4.88) |

0.004* |

|

3,000 - 5,999 SAR |

7 (18.42) |

4 (4.88) |

||

|

6,000 - 9,999 SAR |

4 (10.53) |

9 (10.98) |

||

|

10,000 - 14,999 SAR |

7 (18.42) |

27 (32.93) |

||

|

15,000 - 19,999 SAR |

5 (13.16) |

17 (20.73) |

||

|

More than 20,000 SAR |

2 (5.26) |

10 (12.20) |

||

|

Prefer not to say |

3 (7.89) |

11 (13.41) |

||

|

Do you have health insurance? |

No |

33 (86.84) |

62 (75.61) |

0.227 |

|

Yes |

5 (13.16) |

20 (24.39) |

||

|

Age (Years) |

Median (IQR) |

32.50 (26-39.25) |

33.00 (26.75-41.25) |

0.600 |

|

Health Belief Score |

Median (IQR) |

14 (13-16) |

16 (14-17.25) |

0.030* |

|

System/Access Barrier Score |

Median (IQR) |

3 (1-4) |

2 (0-5) |

0.249 |

*Significant p-value

System and Access-Related Barriers Associated With Follow-up Non-adherence

Participants who reported missing visits related to longer waiting times at the clinic were significantly associated with not attending their scheduled visit (p = 0.020). Other factors investigated did not demonstrate statistically significant associations (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Follow up attendance vs. barrier factors |

||||

|

Scheduled follow-up appointment Attendance |

p value |

|||

|

No |

Yes |

|||

|

Have you ever missed a follow-up appointment due to difficulty contacting the clinić |

No |

31 (81.58) |

62 (75.61) |

0.466 |

|

Yes |

7 (18.42) |

20 (24.39) |

||

|

Was transportation a barrier to attending the follow-up appointment? |

No |

30 (78.95) |

58 (70.73) |

0.344 |

|

Yes |

8 (21.05) |

24 (29.27) |

||

|

Have you missed any follow-up appointments due to long waiting times at the clinić |

No |

17 (44.74) |

55 (67.07) |

0.020* |

|

Yes |

21 (55.26) |

27 (32.93) |

||

|

Was your follow-up appointment scheduled at a time that was not convenient for you? |

No |

22 (57.89) |

53 (64.63) |

0.478 |

|

Yes |

16 (42.11) |

29 (35.37) |

||

|

Was the geographical location of the clinic and its distance the reason for not attending the follow-up appointment? |

No |

29 (76.32) |

61 (74.39) |

0.821 |

|

Yes |

9 (23.68) |

21 (25.61) |

||

|

Have you had difficulty getting an appointment within a reasonable timeframe? |

No |

20 (52.63) |

49 (59.76) |

0.552 |

|

Yes |

18 (47.37) |

33 (40.24) |

||

|

Were you unable to attend because the clinic's hours conflicted with your work or studies? |

No |

18 (47.37) |

51 (62.20) |

0.126 |

|

Yes |

20 (52.63) |

31 (37.80) |

||

|

Was the appointment cancelled or rescheduled by the clinic without prior notice? |

No |

32 (84.21) |

73 (89.02) |

0.555 |

|

Yes |

6 (15.79) |

9 (10.98) |

||

*Significant p-value

Predictors of Follow-up Attendance

The majority of demographic, system/access, and belief-related characteristics had no significant association with follow-up attendance across the three regression models. In Model 1, only monthly family income showed a significant association: participants with <3,000 SAR (OR = 0.094, CI: 0.012-0.753; p = 0.026) and 3,000-5,999 SAR (OR = 0.104, CI: 0.012-0.925; p = 0.042) had significantly lower odds of attending follow-up visits than those who did not report their monthly family income.

In Model 2, none of the health belief, communication, or reminder factors were found to significantly predict follow-up attendance.

In Model 3, the only significant predictor was long waiting time, where participants reporting long waits had over three times higher odds of missing follow-up appointments (OR = 3.27, CI: 1.210-8.863; p = 0.020). No other system/access-related barriers were significantly associated with follow-up attendance (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with follow-up after initial primary care visits |

||||

|

Predictor |

B |

OR |

95% CI |

p-value |

|

Model 1 |

||||

|

Age |

-0.004 |

0.997 |

0.926-1.072 |

0.925 |

|

Male (Ref cat: Female) |

-0.356 |

0.700 |

0.217-2.260 |

0.551 |

|

Employment Status (Ref cat; Employed) |

||||

|

Unemployed |

-0.874 |

0.417 |

0.078-2.225 |

0.306 |

|

Retired |

0.445 |

1.560 |

0.068-35.87 |

0.781 |

|

Student |

-0.400 |

0.670 |

0.125–3.605 |

0.641 |

|

Social Status (Ref Cat: single) |

||||

|

Married |

-19.706 |

0.000 |

- |

1 |

|

Divorced |

-20.036 |

0.000 |

- |

1 |

|

Widowed |

-20.333 |

0.000 |

- |

1 |

|

Educational level (postgraduate studies) |

||||

|

Elementary |

-20.101 |

0.000 |

0.000-0.000 |

0.999 |

|

High school |

-0.358 |

0.699 |

0.699-0.118 |

0.693 |

|

University |

-0.174 |

0.840 |

0.840-0.174 |

0.828 |

|

Monthly family income (prefer not to say) |

||||

|

<3,000 |

-2.367 |

0.094 |

0.012-0.753 |

0.026* |

|

3,000–5,999 |

-2.259 |

0.104 |

0.012-0.925 |

0.042* |

|

6,000–9,999 |

-1.206 |

0.299 |

0.035-2.551 |

0.270 |

|

10,000–14,999 |

-0.767 |

0.465 |

0.066-3.280 |

0.442 |

|

15,000–19,999 |

-0.883 |

0.413 |

0.056-3.034 |

0.385 |

|

≥20,000 |

-0.329 |

0.719 |

0.077-6.755 |

0.773 |

|

Health insurance (Rf cat: No) |

-0.736 |

0.479 |

0.135-1.706 |

0.256 |

|

Model 2 |

||||

|

Communication difficulty |

-0.314 |

0.731 |

0.212-2.523 |

0.620 |

|

Reminder received |

-0.246 |

0.782 |

0.310-1.976 |

0.603 |

|

Health Belief Score |

0.131 |

1.140 |

0.958-1.357 |

0.14 |

|

System Barrier Score |

-0.055 |

0.946 |

0.772-1.160 |

0.596 |

|

Model 3 |

||||

|

Difficulty contacting clinic |

-1.039 |

0.354 |

0.097-1.287 |

0.115 |

|

Transportation problems |

-0.892 |

0.410 |

0.114-1.479 |

0.173 |

|

Long waiting time at clinic |

1.186 |

3.274 |

1.210-8.863 |

0.020* |

|

Inconvenient appointment timing |

-0.372 |

0.689 |

0.235-2.024 |

0.498 |

|

Clinic distance/access difficulty |

0.209 |

1.232 |

0.315-4.824 |

0.764 |

|

Could not book appointment on time |

0.205 |

1.228 |

0.408-3.697 |

0.715 |

|

Clinic hours conflict with work/school |

0.623 |

1.865 |

0.613-5.668 |

0.272 |

|

Appointment canceled/rescheduled by clinic |

0.777 |

2.175 |

0.527-8.980 |

0.283 |

|

Communication difficulty |

-0.156 |

0.856 |

0.204-3.586 |

0.831 |

|

Reminder received |

-0.591 |

0.554 |

0.201-1.525 |

0.253 |

*Significant p-value

Patient-Reported Reasons for Missed Follow-up Visits and Suggested Improvement Strategies

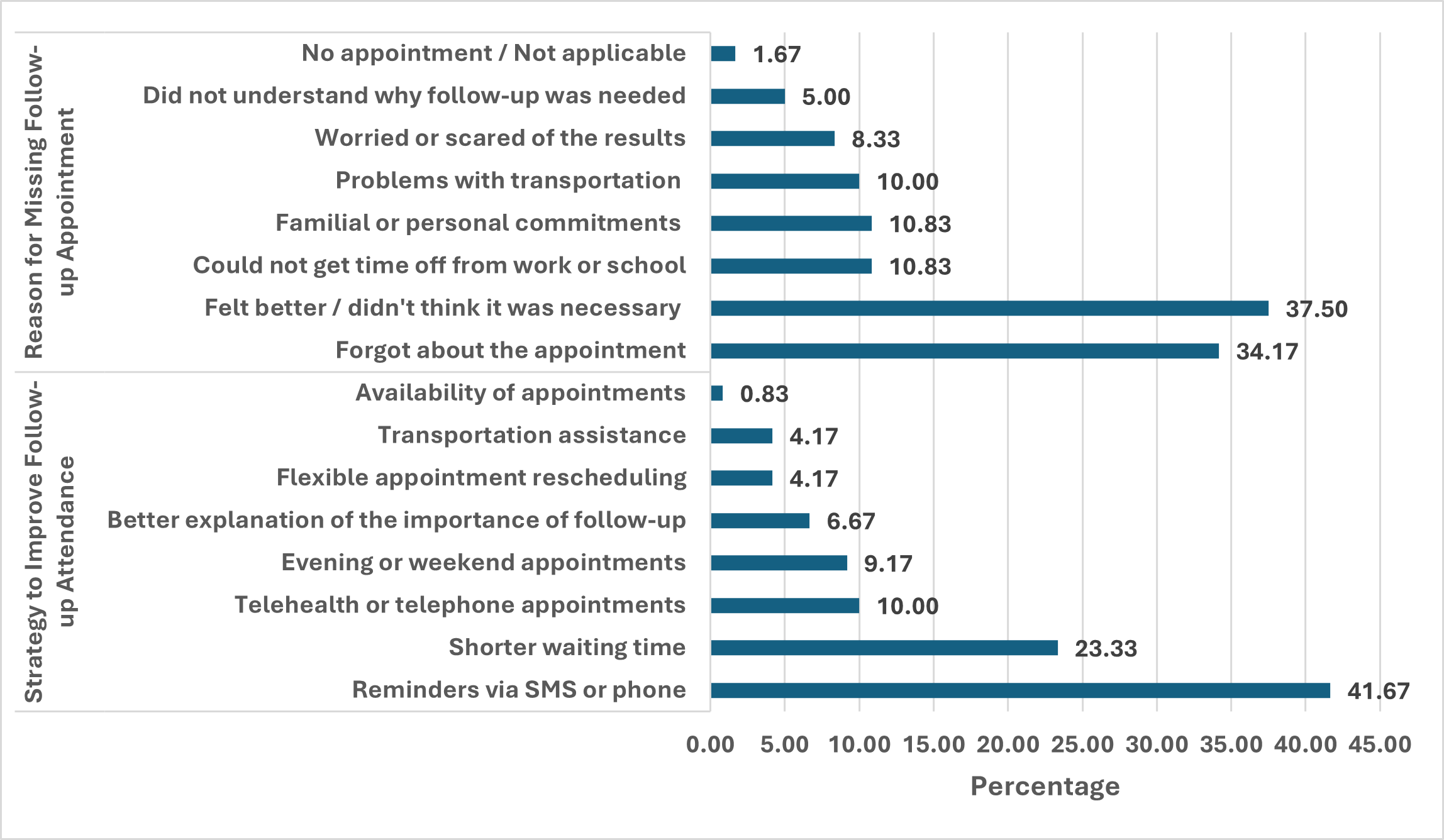

Figure 1 summarized participant-reported reasons for not attending follow-up appointments as well as suggestions for improving follow-up attendance. The two most common causes of missing follow-up appointments were forgetting about them (34.17%) and feeling better or not feeling the need for them (37.50%). The majority of patients recommended reduced wait times (23.33) and SMS or phone reminders (41.67) as important approaches for increasing follow-up attendance (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Participant-reported reasons for missing follow-up appointment and strategy to improve follow-up attendance

Discussion

This cross-sectional study examined the obstacles that keep Saudi Arabian patients from attending follow-up appointments after their initial primary care visits. It also investigated demographic, system-related, belief-related, and psychological predictors of follow-up attendance using patient-reported data from 120 participants who missed scheduled follow-ups within six months. In addition to highlighting particular areas where focused interventions could improve appointment adherence and lessen the detrimental effects of missed follow-up visits, the findings offer comprehensive insight into why a sizable portion of patients struggle with continuity of care.

The generally poor adherence to planned follow-up visits is a noteworthy finding of this study, with 31.67% of the patients not showing up for their appointments, despite being told to return, and 15% of patients missing at least one follow-up. Given the high frequency of managing chronic diseases in primary care settings, these numbers point to significant gaps in continuity of care. The clinical necessity of timely revisit adherence was highlighted by the fact that many follow-up visits were related to laboratory review (40.83%) or case follow-up (28.33%).

A study with nearly the same sample size of 100 patients reported that 36 patients reported forgetting about the clinic appointment, 17 subjects reported work-related issues out of 74 total employed subjects, 9 subjects reported not being notified about the appointment, 6 subjects reported a lack of transportation, 5 subjects reported a problem with the insurance, 2 subjects reported feeling better and not needing an appointment, and 2 subjects reported childcare-related issues as a cause for missing the clinic appointments (18). A cross-sectional survey was conducted to assess the effect of the lab results interpretation on the follow-up, and the results showed a significant impact of automatic interpretations on the decision to follow up on the abnormal laboratory test results (19).

The findings showed that follow-up attendance was significantly correlated with employment status, education level, and monthly family income. This aligns with the results of a qualitative systematic review, which identified financial constraints and socioeconomic factors as significant contributors to non-adherence (20). In line with the hypothesis that stable employment frequently reflects higher health literacy, structured routines, and possibly better access to transportation and financial resources, employed individuals were more likely to attend their appointments (73.17%) than unemployed individuals (10.98%). On the other hand, unemployed people reported lower attendance, suggesting that socioeconomic instability may contribute to delays or failures in follow-up care.

In a cross-sectional study among vulnerable unemployed citizens, they found a high proportion of health literacy challenges, with the most prominent challenge being navigation in the healthcare system (21). Also, a cross-sectional study in Denmark showed that receiving unemployment benefits, social assistance, employment and support allowance, retirement pension, and sickness benefits were significantly associated with having inadequate health literacy compared to being employed in any industry (22). A cohort study also found that patients with full-time or part-time employment had a significantly higher adherence rate than those who were unemployed or retired (23).

Attendance and education level were also significantly correlated (p = 0.009). The highest follow-up rates were shown by participants with university or postgraduate degrees, which is probably due to improved health literacy, a greater comprehension of the repercussions of missed visits, and more adept use of healthcare systems. Significantly lower follow-up adherence was linked to lower education, including elementary or high school levels. This is consistent with a study done on a population aged above 18 years that showed that those with higher educational and employment statuses had higher levels of health literacy (24). It is also consistent with research from around the world demonstrating that people with low levels of education frequently struggle to understand scheduling requirements, medical instructions, and the long-term significance of managing chronic illnesses (25, 26).

Lower-income participants (<6,000 SAR) had significantly lower follow-up attendance and odds of attending appointments, consistent with evidence that financial constraints and socioeconomic factors hinder continuity of care (20). Also, in a systematic review showing the factors that disrupt the continuity of care for patients with chronic diseases during the pandemic, financial problems are among the subcategories that impact the continuity (27). Attendance may still be hampered by indirect costs such as transportation, time off work and caregiving obligations, even though healthcare in Saudi Arabia is primarily subsidized for citizens. This is consistent with a qualitative study showing that transportation challenges, geographical distance, and financial constraints are significant barriers to appointment utilization, with patients’ ability to consistently access healthcare services reported as being affected (28).

Health beliefs and motivations are psychosocial predictors. Health belief scores were found to be significantly correlated with follow-up attendance (median score 16 for attendees vs. 14 for those who did not attend, p = 0.030). This result is in line with research showing that patients who think follow-up appointments are crucial are more likely to come back, while those who think they're feeling better tend to underestimate the risks that still exist. In fact, the most frequent excuse given for skipping appointments was ‘felt better/didn’t think it was necessary’ (37%). This illustrates a common misconception: symptom improvement does not always translate into clinical recovery, especially when it comes to managing chronic illnesses (29, 30). Forgetting the appointment was also very common (34.17%), suggesting inadequate memory support systems and emphasizing the lack or inefficiency of reminder systems (31).

Transportation, clinic hours, scheduling delays, and appointment cancellations were among the system-level barriers that were assessed; however, long clinic wait times were the only factor that were significantly linked to non-attendance (p = 0.020). According to logistic regression, patients who had to wait a long time were three times more likely to miss their next follow-up (OR = 3.27, CI: 1.21–8.86). This result is very similar to that of several studies that found that a major factor in repeat non-attendance is clinic-related challenges, particularly logistics and perceived inefficiencies (32-34).

Regression models showed that socioeconomic determinants, particularly income, were more significant predictors than communication or system barriers. Despite demonstrating a strong bivariate association, the health belief domain did not maintain its significance in regression analysis, indicating that its impact may interact rather than operate independently with socioeconomic factors. The only system variable that was still statistically significant in the final model was lengthy wait times, demonstrating their significant impact on patient behavior. Reminders’ communication issues and clinic hours were surprisingly not significant predictors. This implies that reminder systems may not be used consistently or may not be as effective as they could be.

Patient recommendations for enhancement

Patients strongly supported SMS or phone reminders (41.67 %). Shorter wait times are desirable (23.33 %), which supports the statistical findings and shows that perceived inefficiency is a major barrier to follow-up adherence. Additionally, patients indicated interest in telehealth (10%) and evening or weekend appointments (9.17%), underscoring the need for flexible scheduling, particularly for the majority of attendees who were employed. Those recommendations are consistent with several studies in the literature that address the same issues of non-adherence to follow-up appointments (35-38).

Strengths and Limitations

Personal and perceptual barriers that are not revealed by medical records alone can be better understood by using patient-reported data. The interpretation of the variables influencing follow-up attendance was reinforced by the use of rigorous statistical analyses, such as logistic regression, chi-square analysis, and reliability testing.

The small sample size reduced the statistical power more than anticipated. Generalizability to other areas or healthcare settings is limited by the fact that the study was conducted at a single facility. Reliance on self-reported data increases the risk of recall and social desirability bias, and the cross-sectional design precludes drawing conclusions about causality. The health belief scale's low internal reliability suggests that it still needs to be improved.

Future Directions

Larger multicenter studies employing both quantitative and qualitative methods should be part of future research to better understand the contextual elements and motivations behind missed follow-ups. To assess the efficacy of telemedicine options, extended clinic hours reminder systems, and focused health literacy initiatives, interventional studies are required. The impact of clinic workflow enhancements, which reduced wait times and provided more precise follow-up instructions, should also be evaluated. Effective solutions will necessitate coordinated multi-level strategies because follow-up attendance is influenced by a complex interaction of personal, socioeconomic and system-level factors.

Conclusion

This study identified significant demographic, economic, psychosocial, and system-related barriers to follow-up appointment adherence in primary care settings in Saudi Arabia. Addressing these barriers requires a multifaceted approach, including reminder systems, patient education, clinic workflow improvement, and enhanced accessibility. Implementing these measures could substantially improve follow-up adherence, continuity of care, chronic disease outcomes, and overall healthcare efficiency. After the intervention is implemented, a re-audit is advised to evaluate progress and guarantee long-lasting improvement.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the Hail Health Cluster Institutional Review Board (Approval No. 2025-90, dated 3 September 2025).

Data availability

All data is available within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.