Volume 5, Issue 12

December 2025

Dental Rehabilitation After Pediatric Facial Trauma: Techniques and Outcomes

Ebtihal Abdulfattah Sindy, Muhannad Abdulrahim Alghamdi, Batool Abdullah Asiri, Ghadah Hassan Sumar, Malek Salem Baobied, Nada Mohsen Alsaidi, Ahmed Abdullah Ali Alghamdi, Asim Mohammed Alnawfal, Hussain Masoud Alqahtani

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2025.51210

Keywords: trauma, dentoalveolar trauma, pediatric population, facial trauma, dental rehabilitation

Pediatric facial trauma is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity among pediatric populations. Additionally, facial traumas in children result in about 30% of the dentoalveolar traumas and fractures, resulting in compromised function, aesthetics, and speech, negatively affecting the psychological well-being of the children. Maxillary central incisors are the most affected teeth by dental trauma, due to their position in the oral cavity. Additionally, the presence of an increased incisal overjet or an anterior open bite can act as a predisposing factor, rendering the anterior teeth more susceptible to repeated traumas. Moreover, the anterior malocclusion can exacerbate the impact of facial trauma in terms of loss of function and aesthetics. Maxillofacial traumas can cause neurologic impairment, fractures, or avulsions of the temporomandibular joint, mandible, maxilla, teeth, and supporting structures. Facial traumas can result in the fracture of bones in the middle third of the face, involving the overlying soft tissues, including the paranasal sinuses, tongue, eyes, and nasal airway. Dental rehabilitation of facial traumas is a complex and multidisciplinary process, including different specialties, such as orthodontics, pedodontics, endodontics, oral surgery, and prosthodontics. A thorough examination of the patient immediately after receiving facial trauma is crucial to determining the multidisciplinary treatment plan, especially in pediatric patients, because the treatment plan is often a long-term one. Caregivers’ education about the emergency response in case of facial or dentoalveolar trauma is essential, as timely response in trauma cases can significantly affect the treatment plan, treatment outcome, and prognosis. This review article aims to highlight the complex procedure of dental rehabilitation in children who have experienced facial trauma. The article elucidates the techniques and outcomes of dental rehabilitation, aiming to fill the gap in the existing literature that discusses such complicated procedures.

Introduction

Trauma is considered a leading cause of mortality in pediatric populations; craniofacial trauma is a type of trauma that is significantly associated with mortality in the pediatric population (1, 2). However, the incidence of facial traumas in children is rare, ranging between 1% and 14.7% in children younger than the age of 16, and ranging between 0.87% and 1% in children under the age of 5 (2, 3). The unique ratio of the head to body in children, which accounts for 8:1 in comparison to adults, accounts for 2.5:1 (4). Additionally, in children under the age of 5, the retruded position of the middle and mandibular thirds renders them less prone to sustaining facial and head traumas, whereas the protruded position of the cranial bones renders them more susceptible to trauma (4). Children under the age of 5 are still developing their sensory and motor control systems; therefore, they are prone to accidents and falls. However, as they grow up, the incidence of such accidents decreases (5).

Facial traumas can result in dental traumatic injuries, which are considered a common occurrence in 30% of children and adolescents (6). Such traumas affect the aesthetics, function, and psychological well-being of children. Recent evidence has shown that if the facial and dental traumas were not effectively managed, they significantly affect the self-esteem of children, hence complicating the management of the trauma (6). Traumatic injuries resulting in pain and loss of function can negatively affect the development of occlusion, further complicating the aesthetics, and negatively impact the quality of life of the affected child. Maxillary central incisors are the most affected teeth by dental trauma, due to their position in the oral cavity (7). Furthermore, the presence of an increased incisal overjet or an anterior open bite can act as a predisposing factor. Anterior malocclusion can further exacerbate the results of facial trauma in terms of loss of function and aesthetics (7). Maxillofacial traumas can cause multiple soft and hard tissue injuries resulting in different neurologic impairment and fractures or avulsions of the temporomandibular joint, mandible, maxilla, teeth, and supporting structures (8). The skeletal fractures resulting from facial traumas can be associated with fractures of bones in the middle third of the face, involving the overlying soft tissues, including the paranasal sinuses, tongue, eyes, and nasal airway (8-10).

The dental rehabilitation of children who experienced facial trauma is a complicated and multidisciplinary process. The rehabilitation aims to restore the normal anatomic and aesthetic functions through rehabilitating the soft and hard tissues. Dental rehabilitation requires a comprehensive treatment plan to re-establish soft tissue support (9). Significant trauma in the maxillofacial region can be rehabilitated using fixed or removable prosthodontics to restore teeth and provide support to the lips and surrounding soft tissues. Additionally, bone loss either in the mandible or the maxilla can be restored using a bone graft, then a dental implant to restore the missing teeth, hence restoring function and aesthetics (9).

This review article aims to elucidate the complex procedure of dental rehabilitation in children who have experienced facial trauma. The article highlights the techniques and outcomes of dental rehabilitation, aiming to fill the gap in the existing literature that discusses such a complicated procedure.

Methodology

This narrative review is based on a comprehensive literature search conducted on November 17, 2025, using ScienceDirect, PubMed, Wiley Library, Dynamed, MDPI, Oxford Academic, BMC, and Cochrane databases. The research utilized Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and relevant keywords, such as dental rehabilitation post-facial trauma, to identify studies that examined the techniques and outcomes of the dental rehabilitation process in children. A manual search was also conducted using Google Scholar, and the reference lists of identified papers were reviewed to locate additional relevant studies. No restrictions were applied regarding publication date, language, participant age, or type of publication, ensuring a broad and inclusive exploration of the available literature.

Discussion

Classification of Pediatric Facial and Dental Fractures

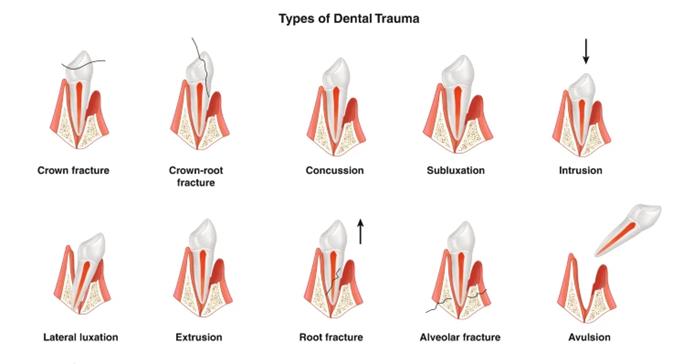

Dentoalveolar fractures can be classified according to the Ellis fracture classification. Class I indicates a simple fracture of the crown of the tooth involving little or no dentin, class II indicates an extensive fracture of the crown involving dentin without pulpal involvement, class III indicates an extensive fracture of the crown involving both the dentin and pulp, class IV indicates a non-vital tooth without loss of the crown structure, class V indicates total loss of the tooth, class VI indicates displacement of the tooth without root or crown fracture, and class VII indicates fracture of the entire crown and its replacement (11). Moreover, there is a classification for the dentoalveolar trauma, including concussion, subluxation, extrusive luxation, lateral luxation, intrusive luxation, and avulsion (Figure 1). A concussion of a tooth indicates no displacement or mobility, whereas subluxation does not result in tooth displacement but results in increased mobility (12). Extrusive luxation indicates displacement of the tooth in an outward direction, whereas intrusive luxation indicates the displacement of the tooth in an inward direction. However, lateral luxation is often associated with fracture of the alveolar bone, which is attributed to the inability of the alveolar socket to contain the lateral movement of the root (12). Avulsions are defined as the complete removal of the tooth from the alveolar socket (12).

Figure 1: types of dentoalveolar traumas (12).

Facial fractures in children are more common in the mandible (33%), followed by the nasal bones (30%), followed by the maxilla or zygoma fractures, accounting for 29% (13). Moreover, soft tissue injuries in children are more pronounced compared to those in adults. The position of the facial nerve is superficial in children, rendering it more susceptible to injury (13). Therefore, pediatric patients with facial fractures often experience a higher injury severity, double the mortality rate, and triple the hospital stay (13).

Diagnosis and Clinical Assessment of Facial and Dental Trauma

Children presenting with facial trauma should receive basic life support that is age-appropriate, followed by evaluation of their facial fractures (14). Pediatric trauma patients have a high cardiopulmonary compensation, with an ability to maintain normal blood pressure despite losing 25% to 30% of the blood volume, which can mask the occurrence of a potential shock. They are more prone to hypothermia, which is attributed to their larger body surface area to body volume ratio. Moreover, the intubation in children is very challenging due to their short, pliable neck, a more anterior larynx, and a flaccid pharynx (13). Computed tomography (CT) is the most common and efficient imaging modality in facial fractures in pediatric patients, since plain radiography is often obstructed by normal anatomic features and pneumatized sinuses (15, 16). Moreover, CT imaging is proven to be efficient in greenstick and non-displaced fractures, which are common in pediatric populations (17). However, CT exposes children to high radiation doses. In cases of mandibular fractures, panoramic radiographs can be an efficient diagnostic tool. As for dentoalveolar traumas, periapical films provide high-resolution images that enable proper diagnosis (13).

The clinical assessment of soft tissue injuries is essential. Determining the presence of facial or lip contusions, lacerations, tongue injuries, or gingival injuries is crucial (18). Bleeding resulting from soft tissue injuries complicates the initial assessment of the trauma; therefore, these injuries should be cleaned and debrided to provide a clean environment, allowing proper diagnosis of the hard tissues (18). Assessing the occlusion of the patient is essential as well. The disturbances in occlusion following facial trauma often indicate a bone fracture or tooth luxation. Determining the etiology of the occlusion disturbance determines the treatment plan that needs to be followed (18).

A thorough examination of the tooth includes examining the presence of crown fractures, the extent of the fracture, whether it exposed the pulp or extended to the root, and the color of the tooth. A change in the color of the tooth after dental injuries can indicate the status of the pulp; it can result from necrosis of the pulp, tertiary dentin formation, or internal resorption (18). Additionally, missing tooth fragments should be investigated in the surrounding soft tissues, especially in sites of lacerations, and confirmed with a radiograph (19). The evaluation of the pulp status after trauma should be inconclusive, as the pulp can stay in a state of shock from one week post-trauma up to three months post-trauma (20, 21). Therefore, the sensibility tests of the pulp should be for the follow-up assessment, not for a final diagnosis. Pulp vitality after traumatic injury can be assessed either through calcifications appearing in the radiograph or the maturation of an immature tooth (18). Endodontic treatment should be initiated only in cases of apical pathosis or the presence of clinical signs or symptoms (22).

Dental Rehabilitation Techniques and Outcomes in Dentoalveolar Trauma

Crown fractures resulting from trauma include enamel infraction, which is a crack resulting from a direct impact of a hard object and requires no treatment (23), and a complete enamel fracture, which is a partial enamel loss with no dentin involved, and can be restored by a composite restoration or by bonding the fractured fragment (23). An Uncomplicated crown fracture is the fracture of enamel and dentin without pulp exposure. This type of fracture accounts for 40% of fracture incidences and can be restored by an adhesive composite resin restoration or a celluloid crown (23, 24). Although full coverage restorations in such cases are indicated, they should be avoided in pediatric patients (25). Complicated crown fractures are defined as loss of enamel and dentin associated with pulp exposure (25). The treatment of such a fracture depends on the level of pulp exposure and aims to maintain pulp vitality (23). For instance, if there is a minute pulp exposure not more than 1mm and the treatment was established soon after the trauma, pulp capping can be done. However, the success rate of direct pulp capping is low (23, 26). If the pulp exposure is bigger and treatment was initiated up to two days after trauma, partial pulpotomy (amputation of the pulp) can be performed to create a dentin bridge under the capping material (23, 26). However, if the exposure is more extensive, the pulp is inflamed, and the treatment is initiated three to four days after trauma, then complete pulpotomy is performed. Complete pulpotomy is recommended in immature teeth to maintain pulp vitality, hence, to continue the maturation of the root (Figure 2) (23, 26). Any of the three approaches requires follow-up for 6-8 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and one year (25).

Figure 2: A radiograph showing the complicated crown fracture before complete pulpotomy (a) and 1 year follow-up after complete pulpotomy and maturation of the root (b) (23).

The last type of crown fracture is crown-root fractures, which are often associated with pulp exposure. There are different approaches to treating crown-root fractures depending on the level of the fracture (24). Crown-root fractures are often oblique, extending 2 to 5 mm subgingival in a palatal direction (23, 25). In such cases, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is beneficial to identify the exact extent of the fracture (23, 25). The treatment of crown-root fractures includes different specialists, such as orthodontists, oral surgeons, endodontists, periodontists, and prosthodontists. The broken fragment is removed, and the remaining tooth structure is examined to decide whether it can sustain a final restoration (23). If the fracture line is slightly beneath the gingiva, a composite restoration or a full-coverage restoration is indicated; however, this treatment approach is challenging due to isolation difficulties (25). Performing a gingivectomy with or without osteotomy to expose the fracture and then restore the tooth is indicated if the fracture line is in a non-aesthetic zone. However, this approach can result in chronic inflammation of the gingiva (25). Orthodontic extrusion of the tooth to expose the fracture line is a less invasive but time-consuming approach requiring 5 weeks to obtain 2-3 mm of extrusion and 8-10 weeks of splinting to retain the tooth in the new position (27). Another approach is surgical extrusion, which is an intentional partial avulsion of the tooth to expose the fracture line, followed by splinting and endodontic treatment of the tooth (23).

Dentoalveolar traumas can affect the root, resulting in a root fracture. Permanent incisors are the most affected teeth, with 75%. However, immature teeth are more prone to displacement than root fracture due to the elasticity of the alveolar socket in young patients. Root fractures can be horizontal, oblique, or vertical. Horizontal and oblique fractures have better prognosis; moreover, simple horizontal or oblique fractures have a better prognosis than multiple ones (23, 28). It is recommended that three periapical radiographs be taken from three different angles to determine the root fracture; CBCT is particularly beneficial in such cases (25). The treatment of root fractures depends mainly on the splinting of the part of the tooth coronal to the fracture to immobilize it. The splint typically remains for 4 weeks and can be maintained for 4 months in cases of cervical root fractures (23, 25). After fixation of the tooth, follow-up is performed at 4 weeks, 6-8 weeks, 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months (23). There are four outcomes following the treatment of root fractures: healing with hard tissue formation (dentinoid or cementoid callus uniting the two root fragments), which is considered the ideal healing of root fractures, healing with interposition of connective tissue, healing with interposition of connective tissue and bone fragments, and healing with interposition of granulation tissue, which is considered failure of healing and the tooth is often sensitive to percussion either vertical or horizontal and an abscess is formed at the fracture line (29). In immature teeth, the pulp often heals and remains vital. However, pulp necrosis occurs in 20-44% of cases; necrosis of the pulp is often associated with the fragment coronal to the fracture, whereas the apical part remains vital (23).

When a traumatic injury results in a concussion, only follow-up is done, and no treatment is needed. If the trauma resulted in subluxation, splinting either passive or flexible is placed for only 2 weeks and then followed up (23). In cases of lateral luxation, bleeding from the gingival sulcus occurs, and the coronal part of the tooth is usually displaced palatally, the root is displaced buccally, and the surrounding alveolar bone is often fractured, interfering with the occlusion (23). A semiflexible splint is placed for 4 weeks to maintain the tooth in its position while allowing physiologic mobility and periodontal healing. The pulp status is then diagnosed and followed by endodontic treatment if needed (25, 30). Intrusive and extrusive luxations are both treated with repositioning, either orthodontic or surgical, followed by assessment of the pulp status to determine the need for an endodontic treatment (23).

Conclusion

Facial traumas are common in pediatric patients and can result in severe fractures, soft tissue injuries, and dental disturbances. The dental rehabilitation of pediatric patients who experienced facial trauma is a complex and multidisciplinary process; however, it often yields favorable outcomes due to the young age of the pediatric patients and the high healing ability of the pulp and surrounding tooth structure. It is essential to educate caregivers and parents about first aid in cases of trauma and the importance of immediate transportation to the hospital, as time plays a crucial role in cases of trauma.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Non applicable.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are embedded within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.