Volume 5, Issue 12

December 2025

Long-Term Effects of Repetitive Botulinum Toxin Use on Facial Muscle Architecture

Nawal Alyamani, Abdullah Aldousari, Fatmah Albloushi, Zainab Alhumoud, Suad Alassaf, Abdelmalek Abdelghani, Mawaddah Alarman

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52533/JOHS.2025.51201

Keywords: Botulinum toxin, Muscle atrophy, Cosmetic complications, Repetitive injection effects, Neuromuscular remodeling

Botulinum toxin, a toxic protein produced by Clostridium botulinum, has gained widespread popularity for both therapeutic and cosmetic purposes. Initially approved for the treatment of conditions like blepharospasm and strabismus, its aesthetic applications have expanded to include glabellar lines, crow’s feet, forehead wrinkles, and other facial concerns. However, the growing use of Botulinum toxin in cosmetic procedures, particularly repetitive or long-term injections, raises concerns regarding its adverse effects on muscle architecture. This narrative review examines the literature on the long-term impact of Botulinum toxin on muscle structure and function. The mechanism of action involves the inhibition of acetylcholine release at neuromuscular junctions, resulting in temporary muscle paralysis. Although the effects are reversible, repeated exposure has been linked to muscle atrophy, fiber disorganization, and neuromuscular remodeling. Several experimental and clinical studies have reported structural changes, including loss of muscle mass, target fiber formation, neurogenic atrophy, and increased endomysial connective tissue. Several studies further support these findings, revealing reductions in muscle cross-sectional area and persistent abnormal signal intensities months after injection. Complications such as ptosis, asymmetry, dysphagia, and aesthetic dissatisfaction are documented, often attributed to toxin diffusion or incorrect injection technique. Moreover, variation in reported complication rates highlights the lack of standardized adverse event reporting. Understanding the long-term consequences of Botulinum toxin is crucial, especially in aesthetic practices where patient safety and treatment precision are paramount. This review highlights the importance of using Botulinum toxin judiciously, adhering to anatomical guidelines, and implementing more robust reporting systems for adverse events.

Introduction

Botulinum toxin is a natural toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum. Botulinum toxin has seven serotypes. However, only serotypes A and B are the only serotypes used for therapeutic purposes (1). Botulinum toxin A was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1989 for therapeutic purposes only to treat blepharospasm and strabismus (1). It is now used to treat depression, hyperhidrosis, migraines, and spasticity (1). However, Botulinum toxin was only approved for cosmetic purposes, such as glabellar lines, lateral canthal lines, and forehead lines, in 2002, 2013, and 2017, respectively (1). The cosmetic uses of Botulinum toxin A expanded to include crow’s feet, bunny lines, glabellar frown lines, perioral lines, dimpled chin, mouth frown, mental crease, platysmal bands, and horizontal forehead lines (2). The FDA in the United States approved the use of Botulinum toxin A in improving moderate-to-severe glabellar frown lines associated with procerus, corrugator muscle overactivity, moderate-to-severe horizontal forehead lines associated with frontalis overactivity, and moderate-to-severe lateral canthal lines associated with orbicularis muscle overactivity (3). Additionally, Botulinum toxin A can treat oily skin by acting as a skin barrier, hence decreasing skin inflammation (4, 5).

Several studies reported that the injecting technique of Botulinum toxin is the most important factor that results in achieving successful results, rather than repetitive injections using the wrong technique or injecting more units (1). Several factors are essential in determining the appropriateness of administering Botulinum toxin injections for cosmetic purposes in patients. For instance, only dynamic wrinkles are suitable for Botulinum toxin injection. Wrinkles that appear at rest and sun-damaged skin are contraindicated from receiving such injections. The distance between eyebrows when treating glabellar lines should be taken into consideration, as it may result in asymmetry or a tired face appearance (6).

The utilization of Botulinum toxin type A for cosmetic applications represents a rapidly expanding field, with over six million procedures conducted by plastic surgeons in 2018 alone (7). However, this expanding use of Botulinum toxin A in cosmetology, especially long-term injections, can result in several adverse effects and complications, such as muscle inflammation, muscle weakness, and muscle atrophy. These complications are attributed to the mechanism of action of Botulinum toxin, which includes the presynaptic blockage of cholinergic nerve terminals through the inhibition of acetylcholine release, resulting in paralysis and a degree of functional muscle atrophy and muscle paralysis (7, 8).

This review article seeks to elucidate the adverse effects associated with the prolonged and repetitive administration of Botulinum toxin injections on the architecture of muscular tissue. By examining existing literature and clinical evidence, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how chronic exposure to this toxin can lead to significant alterations in muscle structure, function, and overall physiology. Furthermore, the implications of these changes are discussed in relation to both cosmetic applications and potential long-term consequences for patients receiving such treatments.

Methodology

This narrative review is based on a comprehensive literature search conducted on June 30, 2025, using ScienceDirect, PubMed, Wiley Library, Dynamed, MDPI, Oxford Academic, BMC, and Cochrane databases. This study employed Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and relevant keywords, including ‘botulinum toxin’ and ‘effect on muscle architecture,’ to identify literature investigating the long-term impact of repeated botulinum toxin injections on muscle physiology in cosmetic applications. A manual search was also conducted using Google Scholar, and the reference lists of identified papers were reviewed to locate additional relevant studies. No restrictions were applied regarding publication date, language, participant age, or type of publication, ensuring a broad exploration of the available literature.

Discussion

The Mechanism of Action and Long-Term Effects on Muscle Architecture

Botulinum toxin is a polypeptide compound; it contains a protein that consists of a heavy chain and a light chain held by a heat-labile disulfide bond. The heavy chain in Botulinum toxin connects to the nerve membrane, which allows the light chain to transport the protein complex. The enzyme of the light chain cleaves the protein specific to the particular neurotoxin. This results in the cessation of neuromuscular transmission, leading to muscle atrophy (9). Additionally, Botulinum toxin blocks the release of acetylcholine at the skeletal neuromuscular junction. This blockage inhibits the transmission of nerve impulses across the synaptic junction to the motor end plate, which induces chemodenervation that results in muscle weakness or paralysis (9). The binding of Botulinum toxin to the motor end plate is permanent. However, this binding paralytic effect persists only for two to six months. This is attributed to the reestablishment of the neurotransmitter pathway, which forms new axonal sprouts. This process results in complete recovery of the transmission pathway, which restores the muscle function (9). Moreover, the therapeutic action of Botulinum toxin requires 24 to 48 hours to initiate. Botulinum toxin often takes this time to deplete the acetylcholine storage in the presynaptic motor end plate (9).

Due to the complex mechanism of action of Botulinum toxin, repetitive or long-term injections can result in several complications in muscle architecture and facial aesthetics. There exists a prevalent misconception among both patients and certain healthcare professionals regarding the applications of Botulinum toxin. It is often believed that this toxin is exclusively utilized for cosmetic purposes, primarily in the treatment of wrinkles, and that its administration is limited to muscle injection (7). However, Rohrich et al. (10) discussed in an experimental study, the relationship between wrinkles, the underlying muscles, and the surrounding structures, such as nerves, veins, arteries, and septa of fat compartments. They underscored the complexity of the surrounding structure and musculature, and that shearing between adjacent compartments can cause soft-tissue malposition (10). Nassif et al. (7) reported in a systematic review that both single and repeated injections of Botulinum toxin type A can lead to real muscle atrophy in both animal models and humans, affecting skeletal, masticatory, and facial muscles. An experimental study conducted by Pingel et al. (11) found that injecting high doses of Botulinum toxin or long-term injections can result in significant microstructural damage to skeletal muscle. Additionally, they used 3D tomographic imaging and found that muscles lost their normal linear organization and symmetry at both levels, fibrillar and non-fibrillar, after receiving high doses of Botulinum toxin (11). Long-term injections of Botulinum toxin can result in metal ion imbalance, oxidative stress, inflammation, satellite cell activation, and muscle atrophy (11). Pingel et al. (11) observed that after injecting Botulinum toxin daily for three weeks, 45% of the wet muscle weight was lost. Another experiment in vivo animal study conducted by Choi et al. (12) found similar results after injecting rats with Botulinum toxin once for 28 days, which resulted in a significant loss of muscle strength. Long-term injections can also result in speech, respiratory, and swallowing issues (8).

A prospective study was conducted by Schroeder et al. (13) in which researchers administered injections of Botulinum toxin to a cohort of volunteers. Following a three-month observation period, the study identified a significantly elevated signal-intensity pattern, referred to as an abnormally high signal-intensity pattern (HSIP), observed in the Short Tau Inversion Recovery (STIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequence. In addition to this notable imaging finding, a considerable reduction in the cross-sectional area of the affected muscles was documented. Remarkably, these alterations persisted over extended periods, with continued observations demonstrating the maintenance of these effects at both six and twelve months following the administration of the Botulinum toxin (13). Histopathological examination of the injected muscles revealed pronounced alterations in the muscle architecture following administration of Botulinum toxin A. These changes were markedly evident when compared to the contralateral control muscle, which remained unaffected. A significant phenotypic characteristic of Botulinum toxin A-injected muscle was the presence of neurogenic atrophy, observed in approximately 30% of muscle fibers (13). In addition to the aforementioned observations, microscopic analysis yielded compelling evidence of a frequent occurrence of target fibers, which serve as a histological hallmark indicating denervation in addition to manifestations of minor fiber type grouping, suggesting alterations in the muscle fiber composition attributable to nerve damage. In contrast, the control muscle samples demonstrated no signs of neurogenic atrophy or the presence of target fibers, thus underscoring the specific pathological effects induced by Botulinum toxin (13). Moreover, several muscle fibers within the Botulinum toxin A-treated cohort exhibited pronounced hypertrophic characteristics. These fibers displayed diameters measuring approximately 100 μm, which notably exceeds the normal maximum diameter of 80 μm typically observed in healthy muscle fibers. This hypertrophy led to an emergent bimodal distribution of fiber size within the affected muscles, indicating significant alterations in muscle fiber architecture. The study recorded a substantial 24% reduction in the mean muscle fiber area in the Botulinum toxin A-injected muscles when compared to the control specimens. This atrophy of muscle fibers was compounded by a mild but statistically significant increase in endomysial connective tissue, thereby reinforcing the concept of a disrupted muscle composition and integrity in the context of Botulinum toxin A treatment (13).

Aesthetic Complications and Challenges in Reporting Adverse Effects

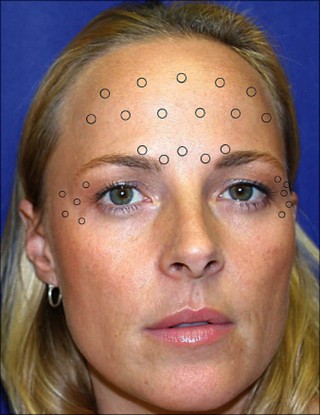

Besides the effect of long-term injections of Botulinum toxin on the muscle architecture, the aesthetic utilization of botulinum toxin is commonly associated with a range of complications that are largely anecdotal and infrequent. Importantly, while most favorable effects of Botulinum toxin are transient in nature, the complications emerging from this therapeutic modality are similarly temporary. These complications can be systematically categorized into two primary types: firstly, temporary, albeit inconvenient side effects; and secondly, site-specific anatomic and functional complications (14). The incidence of complications associated with Botulinum toxin administration remains relatively low, with the severity of these complications generally considered to be mild. A significant determinant in this context is the concentration of the toxin used during the procedure. A higher concentration allows for precise placement of the Botulinum toxin, which subsequently leads to an enhanced duration of effect and a reduction in the likelihood of side effects. Conversely, the use of lower concentrations may facilitate the diffusion of the toxin beyond the targeted injection site, which could lead to unintended consequences (14). There is a predictable area of denervation associated with each site of injection, primarily due to the spread of the toxin. This area has been quantified to be approximately 2.5 to 3.0 cm in diameter around the injection point. At this site, the concentration of the toxin is at its zenith, and the concentration gradient diminishes rapidly as the distance from the injection point increases (14). For instance, Zargaran et al (15) conducted a meta-analysis study on the adverse reactions of Botulinum toxin. They found that Botulinum toxin injection in the glabellar and forehead areas (Figures 1 and 2) can result in adverse effects in only 16%. Headaches and localized skin reactions were the most frequently reported complications among patients receiving botulinum toxin type A treatments. Notably, they observed that facial neuromuscular symptoms and asymmetry were more frequent in the Botulinum toxin group compared to the placebo group. This observation suggests that local skin reactions and headaches may be more related to the injection process itself rather than the botulinum toxin, while facial asymmetry and neuromuscular effects are likely attributable to the pharmacological action of the toxin (15).

Figure 1: Botulinum toxin injection sites for the forehead lines and glabella lines (16).

Figure 2: A comparison between a minimally treated twin (left) and a long-term treated twin (right) (16).

For instance, ptosis of the eyelid or eyebrow, clinically defined as the downward displacement of these anatomical structures, occurs due to a disturbance in the dynamic interplay between agonist and antagonist muscle functions. This complication may arise following cosmetic interventions employing botulinum toxin for the treatment of various aesthetic concerns, including horizontal forehead lines through modulation of the frontalis muscle or frown lines via the procerus and corrugator complexes (17). The onset of ptosis can be attributed to the diffusion of the toxin across the orbital septum, leading to eyelid ptosis, or as a consequence of the compromised function of the lower fibers of the frontalis muscle, resulting in eyebrow ptosis. The incidence of brow ptosis has been variably reported in the literature, ranging from 1% to 2%, and in some cases, it can be as high as 50%, with a reported average prevalence of approximately 13.4% (17). This variability underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of the risk factors associated with these outcomes in aesthetic procedures. This issue can be mitigated by ensuring that injections into the frontalis muscle are conducted at a distance of at least 2–3 cm above the supraorbital margin or 1.5–2 cm above the eyebrow. Adhering to this technique preserves the functionality of the lower frontal muscle fibers in the region, thereby preventing the occurrence of eyebrow ptosis (18). The administration of botulinum toxin targeting the brow depressors tends to result in a modest elevation of the brow in the majority of cases. The eyebrow, a dynamic anatomical structure, is primarily elevated by the frontalis muscle. The medial brow depressors include the corrugator supercilii, depressor supercilii, procerus, and the medial segment of the orbicularis oculi, while the lateral portion of the orbicularis oculi is responsible for lowering the lateral brow (19). To minimize the risk of complications, it is advisable to concurrently address both the elevator and depressor muscles to prevent the unopposed action of one muscle group. Eyelid ptosis has been documented in a case series by Ferreira et al. (20), indicating that complications encountered by patients are likely attributable to the diffusion of botulinum toxin to the levator palpebrae superioris muscle and the extrinsic muscles surrounding the eye, resulting in eyelid ptosis and diplopia. Patients experiencing eyelid ptosis must typically wait several weeks for the effects of the toxin to diminish (21). However, in their 10-year multicenter study conducted by Defazio et al. (22) found that the overall incidence of eyelid ptosis was determined to be 0.71%, while eyebrow ptosis occurred at a rate of 0.98%.

Additionally, Brow asymmetries after injections are common and can result from improper techniques or anatomical variations. The "Spock" brow is a notable example, characterized by a pronounced lateral brow curvature due to the inactivity of the central frontalis while the lateral remains functional. Lip asymmetries, although rare, can occur from incorrect injections below the zygomatic arch or too deeply along the nasal sidewalls. This may affect upper lip elevator muscles, leading to upper lip asymmetry and potential complications like ptosis, which can hinder activities such as speaking and feeding (23, 24). Occasionally, patients may report difficulty in elevating their heads and maintaining an upright posture. A total of 36 reports concerning cervical area complications related to cosmetic botulinum toxin use have been documented. Of these, 30 reports were classified as potential complications from botulinum toxin treatment (25). The possibility of local diffusion or systemic circulation leakage with subsequent distal effects has been described. Diffusion among adjacent muscles enclosed in the same aponeurotic sheath, typically those functioning synergistically or exhibiting similar movements, occurs with relative frequency. However, distant migration via axonal or hematogenous transport remains exceedingly rare [45]. The likelihood of diffusion appears to increase with the administration of a higher total dosage per muscle or long-term injections (26).

However, Other studies conducted by Carruthers et al and De Boulle et al. (27, 28) found high complication rates resulting from aesthetic botulinum toxin injections, ranging between 27% to 43%. In contrast, Sattler et al (29) conducted a prospective study on 381 patients and observed low rates of adverse effects. These different results pose challenges in comparing complication rates across various medical procedures and treatments arise predominantly from the absence of a standardized reporting system for adverse events. An analysis conducted by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the United Kingdom highlighted significant deficiencies in the current methodologies for documenting such complications (30). The lack of uniformity in reporting practices can result in either an underreporting or overreporting of adverse events, which, in turn, may lead to a significant skewing of the safety profile associated with specific medical products. This inconsistency complicates the evaluation of treatment efficacy across different studies.

Conclusion

Repetitive Botulinum toxin injections result in measurable skeletal muscle atrophy, neurogenic changes, and architectural disruption. High doses and improper injection techniques significantly increase the risk of localized and systemic complications. Persistent structural alterations have been confirmed via imaging, histopathology, and clinical observation. Accurate anatomical targeting and dose optimization are essential to minimize adverse outcomes. Standardized, evidence-based reporting protocols are necessary to assess long-term safety in aesthetic applications.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical consideration

Non applicable.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are embedded within the manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to conceptualizing, data drafting, collection and final writing of the manuscript.